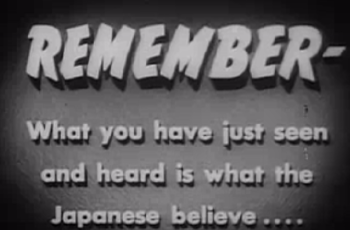

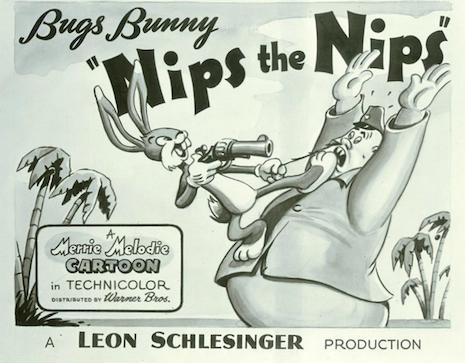

For most Americans, World War II footage acts as their introduction to the banzai cheer. The cheer remains closely associated with militarism and the atrocities of the war. Footage of kamikaze pilots shouting banzai and pumping their arms in unison has a similar chilling effect on people as the Nazi salute. Not to mention the cheer strikes many of us as strange because American culture lacks a true equivalent, except perhaps sport cheers. For anime fans, the cheer appears as a humorous oddity characters perform to encourage others. Finally, for observers of Japan, the cheer appears as a part of politics. You see politicians shout banzai and pump their arms just as the kamikaze pilots had.

For most Americans, World War II footage acts as their introduction to the banzai cheer. The cheer remains closely associated with militarism and the atrocities of the war. Footage of kamikaze pilots shouting banzai and pumping their arms in unison has a similar chilling effect on people as the Nazi salute. Not to mention the cheer strikes many of us as strange because American culture lacks a true equivalent, except perhaps sport cheers. For anime fans, the cheer appears as a humorous oddity characters perform to encourage others. Finally, for observers of Japan, the cheer appears as a part of politics. You see politicians shout banzai and pump their arms just as the kamikaze pilots had.

According to dictionaries, the word banzai literally means ten thousand years. The word’s origins comes from the Chinese word wansui and dates roughly to the beginning of the Meiji period, around 1890 (banzai, n.d.). Banzai is considered an interjection and related to unused English interjections like hurrah and yippee. Perhaps the best equivalent is the British shout “Long live the king/queen.” It can mean “Long live the emperor.” Today, banzai is just a shout of elation.

Banzai and Japanese Emotion Rules

Japan is known for its concern for social appearance or, in other words, emotion rules. Banzai’s explosion of emotion can be jarring, but in Japanese culture, emotions act as “social glue” (Matsumoto, 1996). After all, they aren’t Vulcans. Outward displays of emotion depend on social context, determining how loudly emotions should be expressed.

Japan is known for its concern for social appearance or, in other words, emotion rules. Banzai’s explosion of emotion can be jarring, but in Japanese culture, emotions act as “social glue” (Matsumoto, 1996). After all, they aren’t Vulcans. Outward displays of emotion depend on social context, determining how loudly emotions should be expressed.

A study by David Matsumoto (2002), rated how Americans and Japanese rate external expressions of emotions. Americans rated external expressions of emotion as more intense while the Japanese rated quiet expressions of emotions and louder external expressions equally. The Japanese subjects in the study were also better able to determine true emotions with minimal cues than Americans. This is because Japanese culture contains rules as to how to express an emotion. For the Japanese subjects, the emotional level remain consistent but the outward expression varied due to social appropriateness. Americans lack such rules so we rate the intensity of emotion based on the intensity of its expression. Japanese aren’t better at emotion reading than Americans. Rather, culture frames the way people read and express emotions.

Banzai cheers appear to be high intensity expressions of elation to Americans, but in reality, banzai cheers are socially acceptable outward displays. The actual emotion during a banzai cheer may be as high as a congratulatory smile, but the smile may be the only socially acceptable expression at the time. The cheer serves as a group expression as well.

Despite being a community-focused culture, the Japanese typically don’t have as strong a reaction to world news than Americans and Europeans. Americans and Europeans make fewer distinctions between ingroups and outgroups than Japanese, which is why negative news affects American and Europeans in a personal way (Matsumoto. 2002). This ties together with how Americans view intensity of emotion as well. Because American culture is self-oriented and values individual thoughts and emotions, group dynamics matter less than collective cultures like Japan. Emotional rules developed in Japan as a way to avoid the disruption of social harmony the expression of negative emotions can cause (Novin, 2014).

Tatemae, Honne, and Banzai

This focus on harmony at the cost of individual expression falls under tatemae, or the outward social appearance. This is the set of rules that governs how emotions are expressed in social situations. Honne, or how a person truly feels, often remains unexpressed because it can threaten harmony. In American culture, we have our own version of tatemae and honne. White lies fall under tatemae. So does the suppression of cursing around children. However, because American culture values the individual above the community, our tatemae rules are less pervasive. American culture states it is unhealthy to bottle up our personal feelings. As a result, American culture can come off as abrasive for many.

At the same time, American individualism prevents us from having something like a banzai cheer outside of sporting stadiums and the few other collective venues we have. When you think about it, the chants and cheers of sports seek to create bonds between fans of a certain team. In the same way, banzai cheers form bonds between participants.

Banzai and Anime

Sometimes banzai is used for comedic effect in anime. A scene from Samurai Champloo comes to mind:

The banzai cheer used in this scene is a way of expressing gratitude to the kami of the lake. Kami are spiritual beings found throughout Japanese folklore and Shinto beliefs. The banzai cheer also serves as a period at the end of the comedic scene. The cheer and its role in the anime depends on context.

References

banzai. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged. Retrieved December 18, 2016 from Dictionary.com website http://www.dictionary.com/browse/banzai

Matsumoto, David. 1996. Unmasking Japan: Myths and Realities About the Emotions of the Japanese. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Matsumoto, David,Theodora Consolacion, and others (2002) American-Japanese cultural differences in judgments of emotional expressions of different intensities. Cognition and Emotion. 16 (6) 721-747.

Novin, Sheida, Ivy Tso, and Sara Konrath (2014) Self-related and Other-related Pathways to Subjective Well-being in Japan and the United States. J Happiness Stud 15. 995-1014.

Smith, Herman, Takanori Matsuno, and Shuuichirou Ike (2001) The Affective Basis of Attributional Processes among Japanese and Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly 64(2) 180-194.

The 16 ray flag is raising.

Japan has been increasing its military strength and adjusting its self-defense definitions in recent years.

More like Korean Manse or Chinese Wan Sui.

or Vietnamese Van Tue.

Most cultures seem to have a group cheer of some sort. Huzzah! for the British, for example. It makes sense as an expression of group solidarity.

I am Japanese – I think Banzai can be very innocent. Like when I was a kid and my mom is putting a shirt on me she says to me – ‘Bonzai’ meaning put your hands in the air. When I succeed at doing something, I do the same thing – I put my hands into the air. I think it is almost an international gesture at least, shared by the West And Japan at the least. It like the exclamation “yes! I did it”. For me there are no thoughts of community, Japan, the war or anything else.

Thanks for sharing your experience!

I think the cheer, radio exercise, school uniforms, and command-response cries were process-driven aspects of the culture I initially adored, but as time went on I began to suspect them as driving a kind of mindlessness that would drive conformity to a level contrary to the human spirit.

Thanks for your insight, Stacy. Any collective act, it seems to me, can be used for wrong ends, but such acts can be used for harmony as well.