All of this focuses on women, but men deal with eating disorders as well. It’s just not as well reported. People write much about Barbie’s impossible body type. If you look at boys’ childhood playthings and heroes, you see impossible body standards too. Just look at Superman, Batman, Captain American, and modern-day first-person shooters. These characters have impossible muscles and physiques you can only achieve through steroids and 8-hour daily workout regiments.

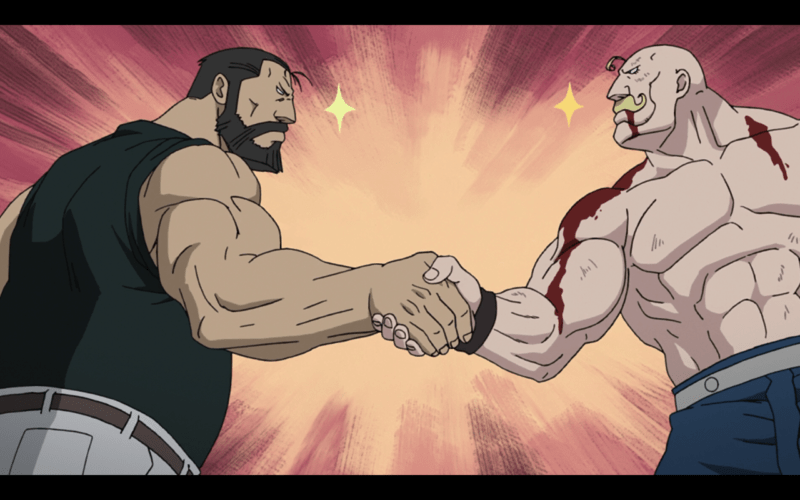

This hyper masculinity extends to anime. Fist of the North Star and Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure have character physiques that become grotesque. This exaggeration blunts their ability to harm a boy’s body image (Or so the reasoning goes. But couldn’t the same argument apply to Barbie?), but it still implants the idea that true men are buff. There appears to be a general lack of concern for male body image in society.

I’m a thin guy, and I could never achieve any sort of musculature even if I tried. It’s just not in my genetics. For a time I tried. I lifted weights and did calisthenics regularly, mainly because I felt inadequate as a thin, stereotypical geek. Surrounded as I was by pecs and biceps in media, I felt the pressure to have them too. After all, that’s what women want, right? I’m also a bit on the feminine side, at least by rural standards. I don’t like to hunt, camp, sit around fires, shoot guns, and do all the other so-called country boy things. I prefer the arts, opera, classical music, metal, writing, reading, and other “feminine” hobbies. Considering there were few geek girls in the area (most girls wanted country boys, which is, again, the culture), my relationships were non-starters until college. So as a teen, I felt pressured by body-image ideals and masculine culture.

I’m a thin guy, and I could never achieve any sort of musculature even if I tried. It’s just not in my genetics. For a time I tried. I lifted weights and did calisthenics regularly, mainly because I felt inadequate as a thin, stereotypical geek. Surrounded as I was by pecs and biceps in media, I felt the pressure to have them too. After all, that’s what women want, right? I’m also a bit on the feminine side, at least by rural standards. I don’t like to hunt, camp, sit around fires, shoot guns, and do all the other so-called country boy things. I prefer the arts, opera, classical music, metal, writing, reading, and other “feminine” hobbies. Considering there were few geek girls in the area (most girls wanted country boys, which is, again, the culture), my relationships were non-starters until college. So as a teen, I felt pressured by body-image ideals and masculine culture.

I didn’t get into anime until my mid-20s. However, the anime that was available when I was a teen fostered the same body-image problems as American media. Dragon Ball Z was the rage in the 90s. The male characters, though not as exaggerated as JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, still fell into the hyper-masculine culture. Buff men appear throughout shonen. To be fair, strength has always been a part of masculine culture. Men went out hunting and fought as warriors. Physical strength, and with its ability to provide and protect, sits at the center of male identity. However, modern media has taken this idea and inflated it, quite literally.

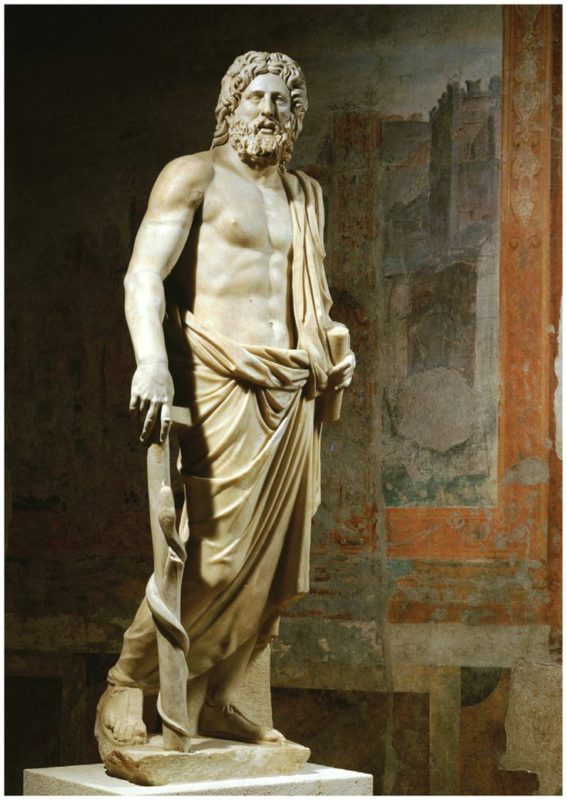

If you look at Western history, heroes and gods were muscular, but not impossibly so. Most statues of male strength were muscles developed through work. They would’ve been fairly common among working class men (at least as long as they were well fed). Among Japanese heroes, you see the same thing. You might even notice less emphasis on muscle than in the West. After all, sumo wrestlers represented strength and vitality. We in the West would just call them fat, and we struggle to associate strength with them. Anime didn’t develop many ultra-buff men until it became an international medium with the popularity of Dragon Ball Z and Akira. Much of this, I suspect, is due to the Western focus on muscle combined with the long exposure of Japan to American culture.

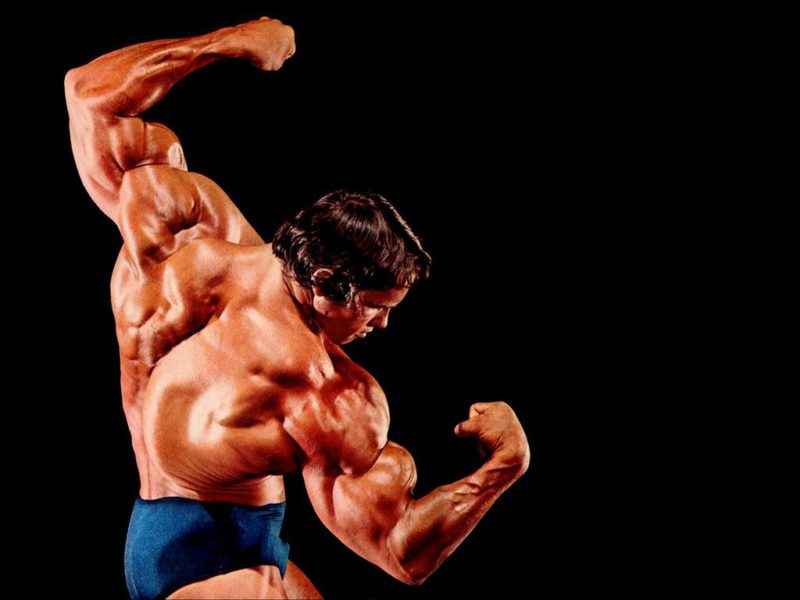

Anime’s increase in buff men appears to follow the same development as muscles in America. Arnold Schwarzenegger could be pinned for sparking the muscle-movement’s fire. While muscles in media existed before him (read this article), his entry into film and multiple wins of Mr. Universe and Mr. Olympia brought bodybuilding back into popular view. If you look at many of anime’s buff men, they resemble Schwarzenegger.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with admiring men like Schwarzenegger. That type of strength has a place in the landscape of manhood. However, when it become the sole definition of manhood, we need to reconsider that definition. It’s much like how shonen anime often shows a single note of manhood–the impulsive protector. I’ve flogged the trope on and off since JP started, but these simplified, unhealthy views of manhood belie a man’s true emotional complexity. Society forces men to bury that complexity. After all, real men don’t cry. Beyond protective feelings, society expects men to be aggressive and angry (which returns to the theme of protection). Passive, calm, thoughtful men aren’t as masculine. These single-notes damage men by forcing them to deny or hide sorrow. They focus too much on impulsive action and aggressive behavior (which can lead to injuries or death) and too little on passivity, peace, calmness, and thoughtfulness.

Society focuses on aggressive male tendencies because they allow manipulation and consumption. Peace, thoughtfulness, calmness, acceptance, and similar virtues work against consumerism. After all, most of us buy things on whims and emotions instead of using careful consideration. Male sexuality –the idea that men always want sex–comes from a similar simplification of the male character. Men behave promiscuously, at least in part, because that is the dialogue they are expected to live up to. It’s how maleness is measured by society. Society’s measure of masculinity sets an insultingly low standard. I consider promiscuous men (and men who fail to wait until marriage or long-term dedication) childish. They follow a base instinct instead of living virtuously.

Virtues are hard to cultivate, but aggression, lust, and dissatisfaction come from the most primal parts of the mind–these are easy. Ironically, the muscular ideals of Western masculinity and shonen require virtue. It takes discipline, thought, calmness, and stick-to-itness to sculpt a muscular body. Media sells the ideals, but encourages the beliefs that prevent you from achieving those ideals. Manhood was once defined by the struggle to be virtuous. It takes discipline and effort to turn sexual urges into a virtue instead of hedonism. Waiting for marriage isn’t easy, but that’s all the more reason to do it. The easy path, by the ancient view of manhood, needs to be avoided.

Before getting into libraries, I studied graphic design. As part of the marketing aspect of graphic design, my classes spent a lot of time discussing the loop of dissatisfaction. People who are impulsive, promiscuous, aggressive, dissatisfied, and agitated buy more than thoughtful, passive, satisfied people. They are also easier to manipulate. I’ve used the word passive often in this article. Shonen, like our one-note idea of men in general, frowns upon passivity. To be passive is a sin. Passivity is the acceptance of an event as it is. You don’t resist it or respond to it. You observe. Passivity means you remain in an open, flexible mindset. Whereas, shonen heroes and men must always resist and react to events. Passivity grants you to space to think through an event rather than merely reacting to it. Of course, passivity can become a vice if you never act. Water is a passive element, yet as the Tao Te Ching observes:

Nothing is weaker than water,

But when it attacks something hard

Or resistant, then nothing withstands it,

And nothing will alter its way.

Anime and manga offers a more water-focused view of manhood, but it’s not the prevailing view. Like Western media, most boys’ manga fall into the hyper masculine ideals of impulsive action, aggression, and lack of thoughtfulness. Anime and manga also subvert a man’s emotional world in the same way as American manhood: don’t cry. Don’t show weakness. If anything, the driving force behind shonen is the desire to become stronger. Sadly, this denotes a growth in power more than in character or virtue. Masculinity needs more focus on an inner life of virtue, but as long as consumerism’s dissatisfaction remains profitably, societies will continue to focus on the easy and the profitable.

Your post focuses on the Shounen genre. I agree that most shounen manga/anime promote that muscular body type, and that boys tend to read shounen more. (I find Kurapika from Hunter x Hunter an exception though)

But there are boys and men who read shoujo and josei too. In these genres, men are mostly portrayed as thin, rarely muscular, but really charming. In my opinion, that shows that not all women find muscular men attractive. Do you think that the guys who read shoujo have different views of the ideal body type?

Shoujo and Josei certainly feature a different body type. This reinforces the idea that muscles make men, however, because these genres specifically aim at women. It works similar to pop culture magazines here in the States. Men’s magazines feature muscles, when women’s magazines often do not. If anything, it shows how the idea of masculinity doesn’t care about female preferences. Rather, it projects male ideas of power (muscles) onto those preferences. It’s possible guys who read those genres have different views of the ideal body type, but the traditional views will also compete. The traditional views generally drown out what shoujo and josei show.

Ah, I see! Yes, the majority will certainly have the upper hand.