Anyone who knows anything about Japan has heard of seppuku or seen it in a samurai film. Seppuku was a ritualized form of suicide and a judicial sentence handed down to men and women of the samurai class. The ritual began on the battlefield with the first recorded case performed by Minamoto Tametomo after his defeat at the Battle of Uji in 1180 (Turner, 2016). For the Japanese of the time, the stomach was thought to be where the soul resided, so slicing the stomach open was a way to release one’s soul. Seppuku would have been a one-off event if it wasn’t for Minamoto Yoshitsune.

Yoshitsune came to embody the ideals later samurai would attempt to live up to, including, when necessary, seppuku. Turner (2016) writes:

The bitter side of Yoshitsune’s legacy is seppuku. His uncle Tametomo was the first recorded warrior to kill himself by retiring from the field of battle and cutting his own belly open. Yorimasa, the elderly Minamoto relative who committed seppuku at the Phoenix Hall, near Uji Bridge, was the second. This uniquely brutal form of suicide might have remained an odd historical footnote had Yoshitsune not decided to die in the same fashion–at least according to the stories that circulated after Yoshitsune’s death. His legend helped turn seppuku into a samurai ideal. Despite what you see in samurai movies, however, seppuku was always an uncommon practice.

As time passed, the suicide of the battlefield developed into a ritual of many steps. Eventually, the painful practice–which also allowed the samurai to linger for a surprisingly long time before bleeding out–involved the use of a second, a kaishakunin to behead the samurai. The kaishakunin began as a trusted friend, but by the Edo period the second was sometimes a governmental affiliate to make sure the execution was finished. The soon-to-die samurai would bathe, dress in a white robe (the color of death in Japan), and eat his favorite foods for a last meal. He would write a death poem and then, as stoically as possible, thrust a knife into his guts. Then the second would slice off his head. In some cases, the second would kill the samurai as the samurai reached for the knife. According to Yamamoto Tsunetomo (Steben, 2008), the second also had special requirements:

From ages past it has been considered an ill-omen by samurai to be requested as kaishaku. The reason for this is that one gains no fame even if the job is well done. Further, if one should blunder, it becomes a lifetime disgrace. In the practice of past times, there were instances when the head flew off. It was said that it was best to cut leaving a little skin remaining so that it did not fly off in the direction of the verifying officials.

For those of us who grew up in Christian countries, where suicide is taboo and condemned and even seen as the act of the weak, seppuku seems strange. Samurai killed themselves for many reasons:

- To erase wrongs and mistakes.

- To escape from disgrace.

- To redeem their friends or family.

- The prove their sincerity.

One warrior story passed down to us, “The Go-Board Cherry Tree,” shows the samurai Saito Ukon beating his lord in go. After several games, Oda Sayemon’s well-known temper flares and he tries to hit Ukon with an iron fan. Ukon catches his wrist–a severe crime for a samurai to do to his master. And he offers a lesson:

“My Lord, it is the better player who wins while the inferior player must fail. If you failed to beat me at go, it is because you are the inferior player. Is this how a defeated samurai behaves? Don’t be so hasty in your anger. It doesn’t befit your high position.”

Enraged by his, Sayemon reaches for his sword. Ukon responds: “Your sword is to kill your enemies, not your retainers and friends.” And then he shows his stomach. He had committed seppuku so he could convince his lord to change his ways. This was what seppuku meant as an act of sincerity. Sayemon’s actions must have been dire indeed to go to such a length to prove a point.

If you think this is strange, you aren’t alone. In fact, Inazo Nitobe wrote Code of the Samurai back in 1900 to explain to Westerners what the ideals of the samurai, called bushido, and seppuku was. For Nitobe, seppuku was the representation of all the samurai virtues rolled into a single self-less act. He points at that the ideas behind seppuku isn’t foreign to the West. Suicide features throughout Western literature and art. He even equates Christ’s death as a type of suicide:

In our minds this mode of death is associated with instances of noblest deeds and of most touching pathos, so that nothing repugnant, much less ludicrous, mars our conception of it. So wonderful is the transforming power of virtue, of greatness, of tenderness, that the vilest form of death assumes a sublimity and becomes a symbol of new life, or else–the sign which Constantine beheld would not conquer the world!

Nitobe didn’t idealize seppuku, however. He wanted to point us past the uncommon act to what it represented, just as the Christian cross represented Christian virtues (among other things). Nitobe writes: “And yet for a true samurai to hasten death or the court it was alike cowardice.” A true samurai didn’t go looking to die or commit seppuku. Likewise Tsunetomo (Steben, 2008) viewed seppuku as a symbol for a samurai’s nonattachment to life, of the Zen ideal of letting go of everything. Only by letting go in this way can a person receive; only by dying to your ideas and misconceptions can you live: “I have found that bushido means to die. It means that when one has to choose between life and death, one just quickly chooses the side of death.” Paradoxically, the samurai’s embrace of death acted as a means of keeping him alive in combat. It allowed him to remain calm and to act in ways that would often ensure survival. For Tsunetomo, seppuku represented the ideals of self-denial, a life of service, and the death of oneself in order to serve others.

Female samurai were expected to act the same as the men. She killed herself differently, by slitting the arteries of her neck. But she also had the added burden of killing her children and sometimes her elderly parents before killing herself. If you want to read more about this, read my article Japan’s Warrior Women.

As you can see, seppuku has a complexity to it that samurai movies don’t touch upon. As Turner and other historians point out, seppuku wasn’t common. It was more common for people to become Buddhist monks or nuns to atone for their mistakes. You see this happen throughout Japan’s warrior legends. The accounts we have a seppuku come down to us because of the circumstances that surrounded the act. We don’t get the quieter accounts of disgraced samurai becoming farmers, merchants, monks, ronin, or otherwise living with their disgrace. I suspect that is because this was more common and because it didn’t follow the ideals of one branch of bushido. Contrary to how we view bushido, it wasn’t a unified philosophical system. Many bushido writers wrote against seppuku, even calling it a dishonorable act (look up Yamaga Soko’s writings). As so often in history, we only get the apocalyptic events and the major personalities involved. The rest of the people, the people like you and me, quietly survive these events and fade from history.

References

Kincaid, Christopher (2021) Tales from Old Japan. Folktales and Legends from the Land of the Rising Sun. Kitsune Publishing.

Nitobe, Inazo (1900) Code of the Samurai. Bushido: the Soul of Japan. Chartwell Books.

Steben, Barry transl. (2008) The Attitude of the Samurai. Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure. New York: Shelter Harbor Press.

Turner, Pamela (2016) Samurai Raising: The Epic Life of Minamoto Yoshitsune. MA: Charlesbridge.

I don’t know if they were documentary or propaganda, but old artworks depicting the fates of captured samurai certainly wouldn’t have encouraged surrender. Perhaps seppuku emerged as a formalized version of suicide to prevent capture? I doubt a woman would even have given it a second thought.

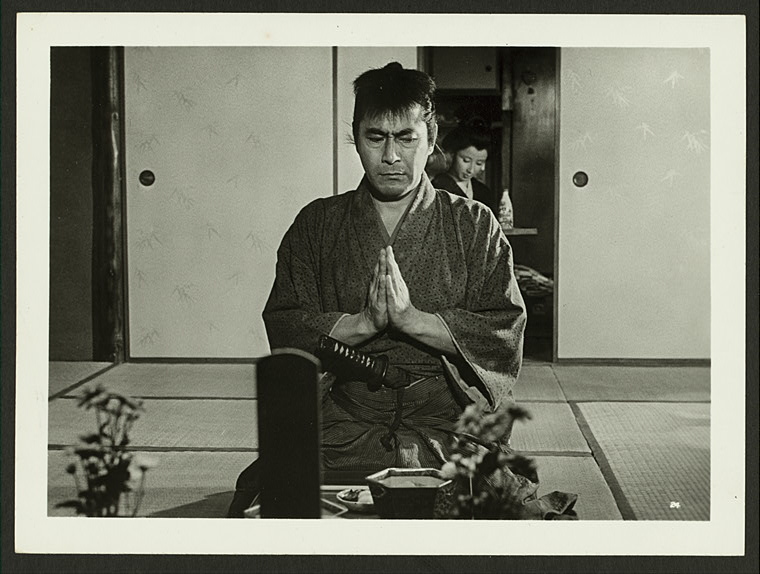

An interesting perspective with regard to its acceptance was presented in the 1962 jidaigeki film, “Harakiri”.

From the historians I’ve read: we don’t know for sure. Japan did have a ransom system similar to that of Europe, so it’s possible those old woodblocks may be showing the rarer, more glamorized samurai stories. After all, European knight stories often have the knights dying in combat rather than be captured — or having some grand escape like Richard the Lionheart. Seppuku seems to have been relatively rare when compared against the samurai population. It may depend on time period and region too.