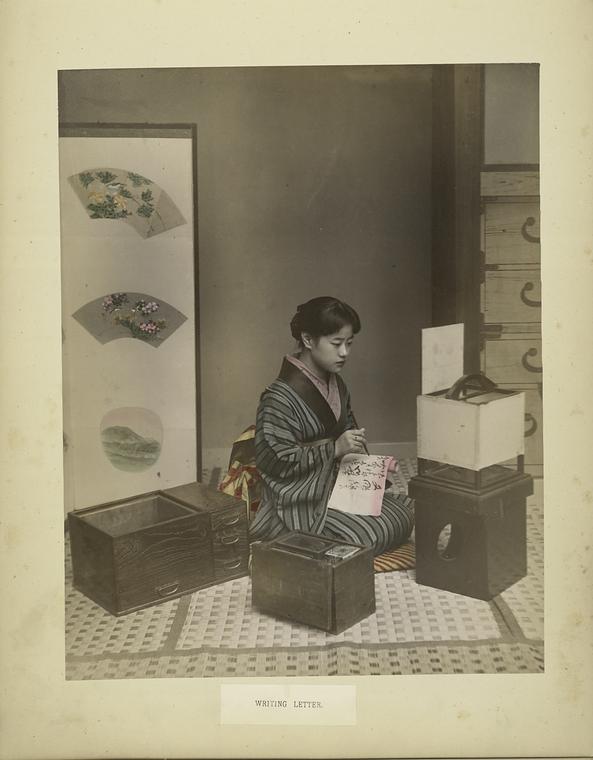

Japan has a long history of literary and artistic women. If you look at the education of women, Japan’s history would resemble a sine curve. Some periods have widespread female education among the nobility and even among some peasant groups. Other periods neglected or limited female education. The most literary women cluster around the Heian period with the giants of Sei Shonogan, Lady Murasaki, and others. Despite widespread education, not all literary or artistic works survive, unfortunately. This is the case for Ryōnen Gensō. Only a few fragments of her work survive: most of her poetry, her paintings, her diary, and her other works were lost through time and, specifically, a fire in 1811. Because most of her works were lost, we have only a few sources–even less in English–that summarize her life and an event that made her famous in her own time.

Ryōnen was born in a mansion outside the gates of Senyuji Temple in Kyoto to a noble family with a lineage stretch back 1,000 years. Her father, Katsurayama Tamehisa, was a descendant of the warlord Takeda Shingen. Katsurayama practiced Rinzai Zen as a layman and was known for his knowledge of old paintings. Ryōnen’s mother served the imperial concubine Tokufumonin and belonged to the court-family Konoe. As an intelligent and beautiful child, Ryōnen followed her mother into imperial service. She worked as a companion to Tokufumonin’s granddaughter and grandson from the age of 7 until she was 12.

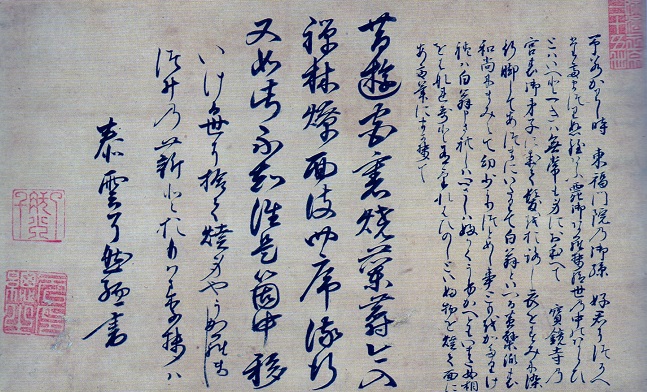

Her father gave her and her younger brothers a thorough education in calligraphy, waka poetry, and the other arts. Both of her younger brothers would become Zen monks.

At around 16 or 17, Ryōnen entered an arranged marriage with the Confucian scholar and doctor Matsuda Bansui. In the 10 years they remained married, Ryōnen had several children. After those 10 years, she became a nun. This may have been a prior agreement with her husband. She also arranged for a concubine to care for her family before leaving for Hokyoji Temple in Kyoto. The temple was led by the Emperor’s daughter Princess Zenni. After 6 years, Ryōnen left the temple to study in Edo.

This decision set her up for the event that made her famous.

When she arrived at Edo, she first went to Kofukuji Temple. At the temple, she was told she was too beautiful to join: she would distract the male monks. She moved on to the Zen hermitage Daikyuan where she met Hakuo Dotai, but he too told her she couldn’t join for a similar reason.

Frustrated, she decided to fix the problem of her beauty. Her account survives:

When I was young I served Yoshino-kimi, the granddaughter of Tōfukumon’in, a disciple of the imperial temple Hōkyō-ji. Recently she passed away, although I know that this is the law of nature, the transience of the world struck me deeply, and I became a nun.

I cut my hair and dyed my robes black and went on pilgrimage to Edo. There I had an audience with the monk Haku-ō of the Obaku Zen sect. I recounted to him, such things as my deep devotion to Buddhism since childhood, but Haku-ō replied that although he could see my sincere intentions, I could not escape my womanly appearance. Therefore I heated up an iron and held it against my face, and then wrote as my brush led me:

Formerly to amuse myself at court I would burn orchid incense;

Now to enter the Zen life I burn my own face.

The four seasons pass by naturally like this,

But I don’t know who I am amidst the change.

In this living world

the body I give up and burn

would be wretched

if I thought of myself as

anything but firewood.

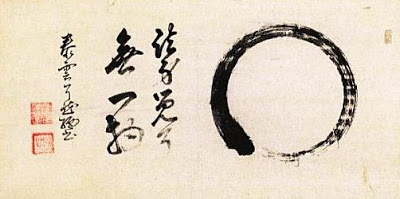

Her self-mutilation made her famous and even appeared in woodblock prints of the time. Fortunately, her extreme act worked. Hakuo allowed her to study Zen at Daikyuan where she became is star student. She earned a certificate of enlightenment in 1682. The certificate marked her as a Zen master and enabled her to start her own temple and practice. Which is what she wanted to do. However, the Tokugawa Shogunate had restrictions against building new temples. The Shogunate only allowed renovation of existing temples, and permission wasn’t easy to get either. After several years of petitioning, the Shogunate gave Ryōnen land in Ochiai, just outside of Edo. She renovated its ruined temple and named her master, Hakuo, the founder. She became the second abbot of this new Renjo-in Temple. In 1701, she expanded the temple into a fully monastery named Taiunji.

Ryōnen used her influence as a temple abbot to build a bridge over a nearby canal and other projects that benefited the area. Although she was known for her facial scarring, she also became known for her scholarship and Taiunji as a learning center. The monastery welcomed children from nearby villages and taught them poetry and other skills.

Ryōnen’s poetry drew attention from the literati, such as this surviving Chinese-style poem:

As old age draws near, inclined towards melancholy as the seasons pass,

I patiently live on, watching the blossoms fall–

As we part, I know it will be difficult to meet again;

Instead I must comfort myself with travel as I face the end of springtime.

She completed a waka poetry collection called Wakamurasaki, or Light Purple in 1691. Sadly this collection, her diary, and other works, including most of her paintings, were lost. Most scholars suspect the 1811 fire destroyed them.

In her 66th year, Ryōnen composed her last poem, her jisei:

In the autumn of my sixty-sixth year, I’ve already lived a long time–

The intense moonlight is bright upon my face.

There’s no need to discuss the principles of kōan study;

Just listen carefully to the wind outside the pines and cedars.

Although Ryōnen’s self-scarring entered her into popular culture in her own time, she proved herself a scholar, poet, and artist. Like the women of the Heian period, her surviving work suggests what was lost and hint at a strong woman of character who cared about the lives of the people around her. Her father had set the stage for her by making sure she had a solid education, but after that, she took the rest of her education and life into her own hands.

Educated women appear to have been more common in Japan than many historians suggest. We have an absence of literary evidence, but considering most of Ryōnen’s works failed to survive, how many more diaries and poems written by peasant children she and others educated were lost?

Ryōnen may not be as well known as Murasaki, but she continues the Japanese female literary tradition. We can hope some of her lost work may yet be found.

References

Addiss, Stephen (1989) Ryonen Genso (1646-1711), The Art of Zen: paintings and calligraphy by Japanese monks, 1600-1925. New York: H.N. Abrams, 94-99.

An unsurprisingly controversial story.

Edo? Kōfuku-ji… in Nara? I suspect that the Daikyuan Zen hermitage is in reference to Myoshin-ji/Taizo-in located a couple of miles west of the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Perhaps off-topic, but Hokyo-ji is an interesting temple… very formal and usually closed to the public. A broken link (replace the “[DOT]”) to a clip from Hokyo-ji. Starting at about 25-seconds, the person at the altar is a Tayu Oiran (not an actor). As of 2015, there were fewer than a half-dozen still practicing in Kyoto through the Wachigai-ya okiya in Shimabara. Public appearances tended to be media events.

youtube[DOT]com/watch?v=eONHabHP77k

I find the names of places in sources get a little garbled. Considering how the Shogunate kept reusing and renovating temple areas, names getting crossed or changed would happen time-to-time.

Interesting video! I had read Tayu Oiran were almost extinct as a profession.

Indeed, with regard to the place names… and I could be entirely incorrect. The limited phonetics often require kanji to differentiate homophones.

There five presently working hanamachi in Kyoto: Gion Kobu and Higashi, Miyagawa-chō , Ponto-chō, and Kamishichiken . The Shimabara district was a yūkaku until prostitution was outlawed in the late 1950’s. It became a hanamachi afterward, but closed in the 1970’s. The Wachigai-ya okiya, however, quietly preserved Oiran traditions. It’s very traditional, invitation only, and not open to the public.

Do you think keeping with the invitation-only tradition contributes to the disappearance of the profession and the geiko profession?

Like the nearly invisible Geisha culture in Tokyo (there are six Tokyo hanamachi), I think it just represents the remnant of a traditional form of cultural ceremony, and a form of “face” among peers in traditional communities.

The working hanamachi in Kyoto survive because they’ve embraced a more accessible, popular version of Geisha culture. You can easily meet Kamishichiken Maiko and Geisha. I had an interesting conversation with a 15-year old Maiko in Kamishichiken several years back. Along with a Geiko, she was entertaining guests at a $22 per Japanese-size (small) glass beer garden. I don’t remember much about the beer, but I was very impressed by her.