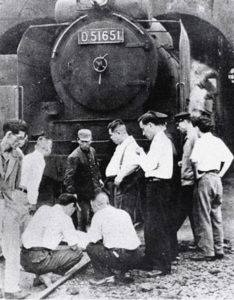

Modern Japan is known the world over for her rail system. The famous bullet trains allow commuters to cross the main island at lightning speeds. Trains played a large role in Japan’s transition from a medieval nation to a modern nation in the late 19th and early 20th century, knitting the country together and allowing for the fast and economical transport of products and people all over the island nation.

After World War II, the Japanese were under American occupation and in the process of rebuilding after the devastating war years. Only four years after the end of hostilities, three mysterious incidents occurred on Japan’s railways that remain unsolved to this day.

The Shimoyama Incident

On the morning of July 6, 1949, Sadanori Shimoyama was found dead on the tracks of the Joban Line between Ayase and Kitasenju stations in Northern Tokyo. Shimoyama, the first president of the Japanese National Railways (JNR), appeared to have been run over by a train during the night. He had been missing since the day before. He’d stopped at the Mitsoukoshi department store in Nihonbashi on his way to the office.

The death immediately caused speculation. His death came as the JNR was in the process of job cuts. Some believed he committed suicide due to the stress of his position, while others believed he was killed by leftist radicals. Still others pointed the finger at the Occupation authorities. JNR security headquarters and the Tokyo District Public Prosecutor’s Office conducted its investigation assuming that Shimoyama had been murdered. The investigation focused on three areas: patrons of a restaurant Shimoyama frequented, JNR employees at the deport from which the train suspected of running down Shimoyama departed, and chemical analysis of oil spots on his clothing.

Of 15 JNR workers questioned at the depot, none were suspected of any involvement in the death. A worker claimed to have overheard someone implicating himself in the killing, but this lead led nowhere. A person seen in the restaurant was briefly under suspicion, until they were revealed as an investigator from the Metropolitan Police Department.Finally, the oil spots eventually led nowhere.

A theory, unsubstantiated, was put forward by prosecutors that Shimoyama visited an acquaintance at the Misukoshi store, only to be later taken somewhere by a car owned by the Soviet Union. However, there was no evidence to substantiate this theory. The crime, if there was one, remains unsolved.

The Mitaka Incident

Only nine days after Shimiyomo’s death, disaster struck Mitaka station in western Tokyo. An unmanned train started moving, breaking through a track end bumper and plowing into the station and nearby structures. Six people died, and another 20 were injured. Station workers and onlookers worked quickly to rescue victims, but soon US military police took control of the accident site and barred the public from the site.

Not long after the incident, 10 members of Japanese National Railways, a rail worker union, were arrested and charged in the crash. Nine of them were members of the Japanese Communist Party. Prosecutors alleged that the group conspired to cause the runaway train in order to get revenge against the JNR for its plan to dismiss workers in large numbers. The union ranks were made up of disgruntled workers, Communists, and Communist sympathizers, many of whom resented the government and the Allied Occupation.

Of the accused, only one man, Keisuke Takeuchi, who wasn’t a member of the union, was convicted. He confessed to his role in the crash, but eventually recounted and claimed innocence. He was initially sentenced to live in prison by the Tokyo District Court, while the Tokyo High Court overruled the lower court verdict and sentenced Takeuchi to death by hanging. The Supreme Court upheld this verdict. In 1956, he filed for a retrial. He eventually died of a brain tumor in January 1967 at the age of 45. The case against Takeuchi was closed soon after.

The third incident to occur in 1949 occurred only a month after the Mitaka incident. On the rail tracks between Matsukawa and Kanayagwa stations, train cars derailed, killing three railroad men and injuring eight passengers. As in the Mitaka incident, police and prosecutors immediately looked at rail workers who were members of unions, and by extension the Japanese Communist Party.

Workers were convicted in both district and high court, and 5 of the 20 were sentenced to hanging. However, as the trials wore on, shady doings on the part of the police and prosecutors were soon revealed, including forced confessions, mishandling of evidence, and coercion. The defendants claimed innocence, and the revelations of police misconduct put public opinion on their side. Writer Hirotsu Kazuo formed a national council on the incident, which looked into the evidence of the case and showed beyond any doubt that the rail workers were not to blame. In 1963, all workers were found not guilty by the Supreme Court. The actual culprits were never apprehended.

An enduring mystery

These three incidents–all of them occurring in one year and all involving railways–remain an enduring mystery in Japanese crime history. Most seem to believe that the Occupation and the government worked together in an attempt to discredit both the labor unions and the Japanese Communist Party. This is very possible. It is also good to bear in mind that the incidents took place against a backdrop of political turmoil and a labor dispute, a recipe for bad feelings and rash actions. So, it is possible the acts were perpetrated by disgruntled union workers, or lone wolfs bitter about losing their livelihood to job cuts.

Whatever the case, it is unlikely that the true culprits of the tragedies will ever be caught. The Japanese Railway Incidents will remain a mystery for decades to come.

Sources:

Hirano, Keiji. “’49 Mitaka Incident retrial sought.” JapanTimes.co.jp. December 24, 2010. The Japan Times. May 17, 2015. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2010/12/24/national/49-mitaka-incident-retrial-sought/#.VWIOO0Z2Zdh

Kaplan, David E. and Dubro, Alec. Yakuza: Japan’s Criminal Underworld. University of California Press. 2012. pgs 46-47

“National rally marking Matsukawa Incident’s 60th anniversary.” Japan-Press.co.jp. October 18, 2008. Japan Press Weekly. May 17, 2015. http://www.japan-press.co.jp/modules/news/?id=771&pc_flag=ON

“‘Shimoyama Incident’ memos uncovered.” Japantimes.co.jp. July 4, 2002. The Japan Times. May 17, 2015. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2002/07/04/national/shimoyama-incident-memos-uncovered/#.VWIOP0Z2Zdhsa=X&ei=8_pYVdyVLMLAgwTuvoDoDA&ved=0CGMQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&q=matsukawa%20incident&f=false