Her father died when she was 14, leaving her in the care of Go-Fukakusa. Unfortunately, the teen had earned the ire of the Retired Emperor’s principle wife. The teen also failed to prove as fertile as the principle wife, which she discusses in Confessions. The final mistake, which cost her status in court, was to take on a lover: Go-Fukakusa’s brother Emperor Kameyama.

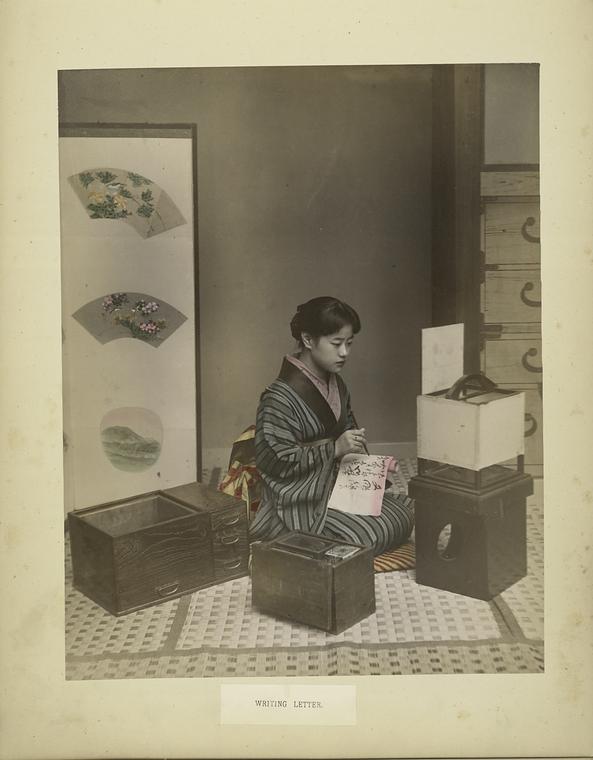

Confessions contains Lady Nijo’s observations of the court, her experiences as a concubine (or wife. Her status wasn’t entire clear), and later, her journeys as a nun. The early part of the diary feels fresh and personal. Lady Nijo has a direct writing style that conveys her emotions and thoughts in an intimate way. As with other well-read writers, she makes many allusions to other works, such as The Tale of Genji and Tales of Ise. She also collects poetry, such as the love poems Go-Fukakusa sent to her and her own responses.

Lady Nijo was made the Retired Emperor’s concubine against her will. Yes, she was raped when she was 14, although at the time, it would not have been considered rape. I will be quoting her accounts of this event, so you should stop reading if this is a troubling subject for you. Her account is valuable for understanding how the Imperial court of the time functioned and women’s place within in. I will add that Lady Nijo seems to have developed love for the Retired Emperor, but survival also played a role in this. After all, she lost her father in the same year. A fatherless, unmarried young woman had few options in medieval Japanese society. Furthermore, her father arranged for the honor of being the Retired Emperor’s favorite concubine. That status did lend her special privileges women otherwise couldn’t enjoy, such as gaining an education and the ability to have some autonomy as Confessions illustrates.

However, after she become pregnant, the Retired Emperor stopped visiting her as often. His principle wife demanded more of his attention. The isolation Lady Nijo felt, the jealousy and guilt toward that jealousy, make you feel for her. While the status of teen didn’t exist at the time she wrote, her prose reminds you of how young she was.

In any case, here is a translation of her rape by Go-Fukusa:

Some time later, I started awake to find the lamps dim, the curtains apparently drawn, and a man lying near me at his ease, just inside the doorway. In a panic, I tried to rise and flee, but he held me down. “You’ve haunted my thoughts ever since you were a little girl. I’ve been waiting for you to turn fourteen.” He said other things–so many that I have no words to record them all–but I merely wept without listening. My tears drenched his sleeves, to say nothing of my own. Unable to sooth me, he did not resort to force but said, “I’ve felt frustrated for so long that I decided to seize this opportunity. Other people must have made assumptions about us by now. Do you think a display of coldness is likely to end the relationship?”

After that night, Lady Nijo wrote about how she couldn’t see her father in the same way as she had the day before. After all, he had arranged for her “meeting” with the Retired Emperor. The next night, the Retired Emperor returned after he exchanged poems with her through messengers throughout the day.

The day drew to a close. I refused to swallow anything, even hot water, and my attendants told one another that I must truly be ill. At twilight, I heard people announcing His Majesty’s arrival. No sooner had I begun to wonder what would happen this time than the door opened and he entered with a nonchalant air. “They say you aren’t feeling well. What’s the matter?” he asked. I merely lay there, unwilling to answer. He stretched out beside me and murmured all kinds of endearments. There seemed little alternative to say, “If this were a world…” But I also felt that it would be too heartless to disregard the emotions with which someone else would learn that the evening smoke had suddenly trailed off in one direction. At my wits’ end, I made no reply at all.

His Majesty’s behavior that night was callous. I think my thin robes must have ripped rather badly, but he did as he pleased with me. I hated being alive, hated even the dawn moon. The words a poem kept running through my mind:

When, in days to come,

might gossip sully the name

of someone whose robes

have had their strings unfastened

through her heart did not consent?

It’s hard not to feel angry when reading Lady Nijo’s account here. She was 14. Yet, when looking at history, we can’t apply our modern morality, as much as we would like to condemn such events. I failed at this idea when I read this section. Her father, no doubt, did what he thought would be best for her and for the family. After all, Go-Fukakusa would have pursued her regardless of what Lady Nijo’s father did. He was the power behind the Imperial throne. The Retired Emperor had his sights on her since she was a little girl. At the same time, because of her father’s arrangement, Lady Nijo enjoyed a life and a quality of material comfort few could achieve at the time. She was well-educated, and when she became an aristocratic nun, gained independence a commoner would not have had.

Lady Nijo’s rape by the Retired Emperor didn’t keep her from later taking on a lover. That time, she had a choice, which she reflects upon in those sections.

Confessions of Lady Nijo is a fascinating, troubling, and human read. It offers insight into a time-period dominated by male voices and gives an insider-female view on the Imperial court. Her later travels are also interesting. Even through the English translation I read, her voice and personality shines through. I would recommend at least reading sections of The Tale of Genji, Tales of Ise, and other older literature so you can understand some of Lady Nijo’s references. She isn’t as oblique as some writers, so the references are easier to understand. She also doesn’t rely solely on them to get her point across. She is quite a direct writer compared to other Japanese writers. Diaries like Confessions prove invaluable for understanding the personal lives behind the facts and political accounts that usually dominate history. When you read history, it is easy to forget that the people you read about hurt, loved, hungered, and laughed. Confessions reminds us of how human history really is.

References

Craig McCullough, Helen (1990) Classical Japanese Prose. Stanford University Press.

The Confessions of Lady Nijo is a beautifully written Buddhist work. Japan has not a few women writers who are geniuses.

Japan’s female writers are fascinating reads. They ought to be a part of English or history class readings.