History has two different and related types: small and big. Big history is what you learn in school. It’s the major events of the past: the American Revolution, World War II, the Thirty-Years War, Sengoku Jidai, and so on. Big history usually has some sort of date you needed to memorize. Small history sits on the ground. It’s the personal stories that interact with big history. Big history influences small history, and small history pushes big history.

Big history has many people writing about it and suffers from the victor problem. The victor problem is the idea that history is written by the winners of the conflict. While this isn’t always the case, big history tends to develop trappings of legend. In the US, we refer to the Founders with a capital F, which is a contrivance of legend. Figures in big history tend to lose their humanity over time. George Washington has developed the clothes of deity similar to what some Roman emperors tried to wear in their own lifetimes, for example. Some of this comes from how big history is oversimplified so it can be taught to children and to the citizenry in a short amount of time.

Small history gets into the mud of history, the nuances behind big history. Small history deals with, say, how Benjamin Franklin felt disrespected by the British Parliament or how Benedict Arnold fell in love with a British Loyalist. Many of these small events pushed people in a direction that helped push big history. One of my favorite examples of this comes from the story of Kitanomandokoro. Kitanomandokoro was the first and most beloved wife of Hideyoshi. Her words helped sway the direction Japan would take, and she even had a hand in the pivot battle of Japanese history: the Battle of Sekigahara. Her story is small history and provides a good example of how the two types of history influence each other.

However, Kitanomandokoro’s small history is a rare exception. Most of the time, we don’t know much about the people involved in the events of big history. At least, not until the modern period. But despite having the writings of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and George Washington, classroom instruction ignores small history and how it shaped big history. Of course, good historians will dive deep into this in their books, but it hurts people’s understanding of their own culture when the education system fails to go into small history.

A common gripe I encounter: “Why should I learn history? It’s not useful for today.” People aren’t wrong in this. Learning big history, while it provides some context, doesn’t really impact people’s daily life. However, small history can help people make better decisions. When you understand the challenges, conflicts, and personal costs people faced during big history events, you can better understand how to navigate your own big history. And all of us live through big history. While in the midst of change and events, you often aren’t aware of them. We live in big history events right now with how technology, climate challenges, financial shifts, and the usual problem of war are changing the trajectory of civilization. At some point, each of us will have to make a decision based on how big history affects us. Understanding how people in the past faced their own big history can offer some guidance, even if that guidance is what not to do.

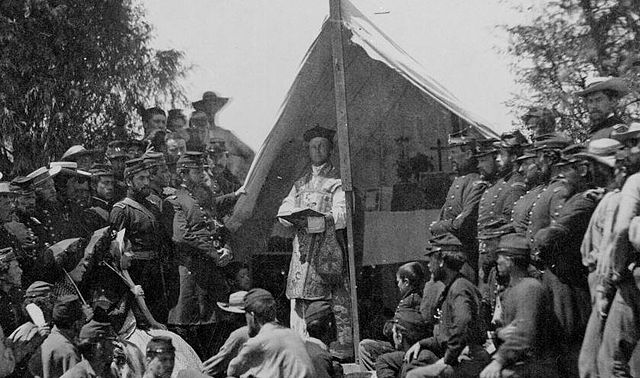

We often forget that historical outcomes weren’t known by the people who lived them. It’s not like George Washington knew the American Revolution was going to succeed or Kitanomandokoro knew her letter would influence several lords to take the side of Ieyasu during the Battle of Sekigahara. When you read or consider small history, you need to forget the outcome of events. When you embrace the uncertainty the people of the past felt, you learn more. This, in turn, helps you apply their examples to your own life and its uncertainty. While history only preserves–at least sometimes–the thoughts of those involved in events, even the commoner had to deal with the outcomes. Consider what a farming family would have had to decide during the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The breakdown of stability, infrastructure, and even the monetary system would’ve been difficult to handle, to say the least. Unfortunately, we don’t have direct accounts about how such families acted.

Taking the opposite perspective of big history helps you understand small history. Another example: American history frames those who remained loyal to the British Empire as traitors. However, these people were just living their lives as they always had done. The “patriots” were the ones who were breaking with the norm. They were the traitors. Now, consider the fact every colonist would have to decide which side to support: the upstarts or the status quo. I don’t know about you, but I would’ve sided with the status quo. First, I would’ve already been a British citizen, if a lower class one as a colonist. Second, declaring as a patriot would’ve required me to change how I lived, perhaps moving out of a British-controlled area. Third, the Americans weren’t destined to win. By all regards, the American Revolution should’ve failed, and I would’ve expected it to have failed.

Putting yourself into history like this only works if you are honest about what you may do and if you consider the difficulty of the dilemma based on what we know of the small history. Such a thought experiment can help you navigate today’s big history by making you think more deeply about circumstances and yourself.

Big history, while important to understand, lacks the usefulness of small history. Small and big history interact with each other, with big history defining people’s actions and people’s actions (and sometimes flukes) shaping big history. When people say they don’t like history or find history not useful, they haven’t looked into small history. Understanding how people lived and navigated events helps you navigate today. Unfortunately, small history is scarce and largely lost.

That is, unless you consider folklore.

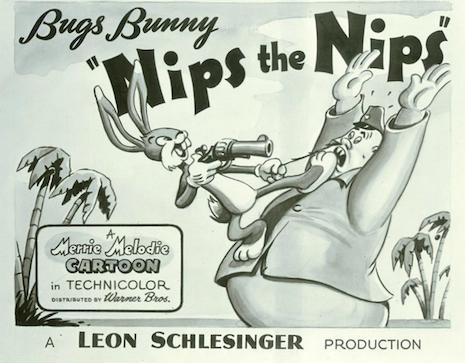

Think of folklore as small history trapped in amber. While folklore deals with fictional stories, the stories contain concerns, views, and lessons from people living through big history. These stories distill the experiences of small history into axioms and stories that teach us how to navigate our current big history. Sometimes a folktale acts as a metaphor for big history and how people would ideally–or not so ideally–choose to react to the event.

So whenever you consider history, ask yourself if what you are reading is big history or small history. Remember that both types of history depend upon each other. However, small history often provides the most applicable lessons for your daily life.

Indeed… Canadians have a quite different perception of “American” history.

This is among the reasons I encourage going to primary sources whenever possible. During my college years, reading just the letters exchanged between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson left me with a very different perception of the founding of the US and what it was really all about.

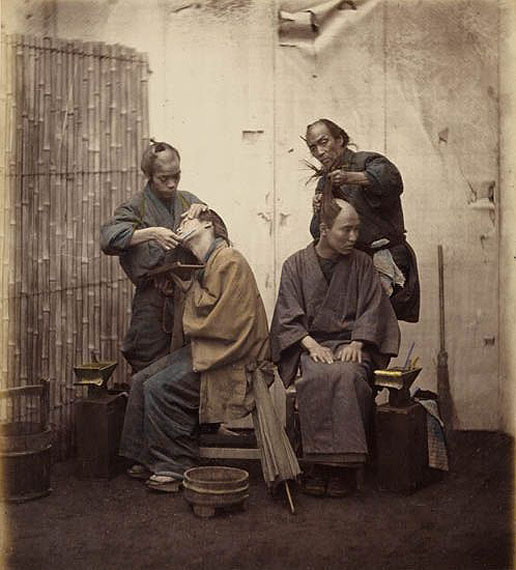

Unfortunately, ordinary people rarely left behind significant writings; or else, they rarely survived much into posterity. One of the reasons I’m fascinated by reading such as Kaneko Fumiko’s prison diaries is that these are rare insights into the everyday lives, challenges and experiences of ordinary people. I also feel that history tends to be re-interpreted through the values of intervening cultures, even over time. So reading in context, perhaps even with an understanding of the original language can be important. Recent re-inventions of British and Egyptian history come to mind. And Japan is certainly the subject of much romanticism.

The founding of the US is far messier and fraught than Americans are taught in school.

I was excited to read about Assyrian letter tablets that have been found. Sometimes the letters from ordinary people survive and wait to be discovered. We can hope more will surface over time.