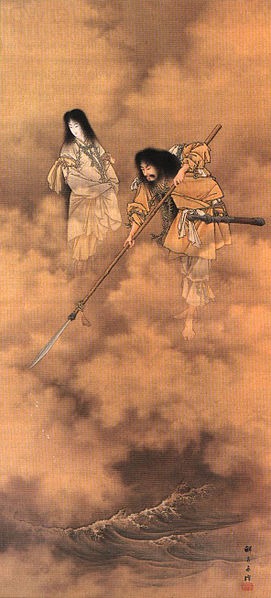

Taoism, or Daoism depending on which transliteration system you want to use, like many Chinese imports, mixed with Japan’s culture and the native religion Shinto. Although calling Shinto a unified religion is an oversimplification, let’s just go with it for now. Like Taoism’s venture into the West, the philosophy took root in Japan more than the rituals. Taoism has its own set of priests, monks, and rites that, as far as I can tell, didn’t take root in Japanese history. Instead, and like Buddhism, they merged into what already existed. This isn’t the say you can’t find Taoist temples or practices–just as you can find throughout the West, but they didn’t take off as much as the philosophy.

By the way, my Chinese friends tell me Tao is produced “dah”. They find my American pronunciation of “dow” amusing. They tell me Americans often pronounce imported Chinese words with an “ow” sound.

Taoism centers on the Way. The Way is an alignment with how existence is. Think of a canoe in a river. You can paddle against the river and make little headway for a lot of effort. Or you can flow with the river and direct the canoe with little effort. This is the way life works. The Way focuses on the interplay of wholes; light and dark make a whole because they cannot exist without each other. The famous yin-yang symbol represents this interplay. It’s not yin and yang, which separates them. Yin-yang represents a flow of seeming opposites which create the whole. The opposing forces each contain elements of the other and cannot exist without the other. You can’t understand happiness without sorrow, heat without cold, life without death. Under standard dualistic thinking, these work against each other, but in Taoism, opposites create wholeness. We humans create artificial conflict and division where there is none. If you are familiar with Buddhist thinking, this shouldn’t be a new idea. The Way, according to Taoism, goes beyond all thoughts and labels. As the Tao te Ching, the principle book of Taoism and written by Lao Tzu, states:

The Tao that can be told is not the eternal. The name that can be named is not the eternal Name.

It is existence or, to borrow a deep Judeo-Christian concept, the I AM. Only unlike God, the Way doesn’t have a personality. It’s a set of principles and realities. The Tao te Ching often uses the metaphor of water to illustrate its point:

The gentlest thing in the world overcomes the hardest thing in the world. That which has no substance enters where there is no space. This shows the value of non-action. Teaching without words, performing without actions: that is the Master’s way.

And the book discusses the value of doing only what is necessary and to keep yourself empty of expectations and opinions:

It is easier to carry an empty cup than one that is filled to the brim. The sharper the blade the easier it is to dull. The more wealth you possess, the more insecurity it brings. The more you care about other people’s approval the more you become their prisoner.

Do your work, then step back. This is the only path to serenity.

These ideas merged with Zen Buddhism, Confucianism, and Shinto to create Japan’s philosophy that wasn’t a philosophy: bushido.

I call bushido a nonphilosophy because it didn’t become one until around the 1900s. Before then, it was a general attitude that had different ideas scattered throughout Japan’s regions. The form that become dominate, and what we know of today, held up honor, ritual suicide, and self-sacrifice. However, bushido had many other writers such as Ekiken Kaibara who wrote against suicide and the death cult aspects of bushido. These writers intertwined Taoist beliefs with Zen to create a gentler (but still war-focused) version of bushido. You can find Taoist principles throughout both branches of the samurai ethos, such as speaking little:

You should also be circumspect in your speech, cut down on useless conversation, and become a person of few words. –Ekiken Kaibara

Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know. –Lao Tzu

Of course, Lao Tzu write about knowing the Way, which loses something when spoken about, but bushido writers like Ekiken grabs onto the principle.

Taoism’s understanding of the mind overlaps with Buddhism’s understanding, so you can’t tell which tradition (likely both) writers like Yagyu Jubei Mitsuyoshi taps when he writes:

The undisturbed mind is like the calm body water reflecting the brilliance of the moon. Empty the mind and you will realize the undisturbed mind.

And a similar quote from the Tao te Ching:

Do you have the patience to wait till your mud settles and the water is clear? Can you remain unmoving till the right action arises by itself?

If you read any samurai writer, you see Taoism sprinkled throughout their works. Taoism’s idea of emptiness is almost identical to Zen’s idea. Emptiness is a state of mind devoid of labels and opinions and thoughts. Such a mind experiences reality, the Way, as it is without anything mediating it. To put it a different way, the ego disappears and you experience life without feeling separate from it. Can you see why Lao Tzu says those who speak don’t know? The Way, the void, cannot be put into words. It can only be experienced. It feels airy and unattainable, yet the Way, the I AM, the void is always there. Only your thoughts, labels, and opinions stop you from experiencing it. I don’t like to discuss it–mainly because, again, words fail–but I’ve experienced the void while hiking and meditating. The experience doesn’t last long, but when your mud settles and you see reality as it is, your perspective forever changes. And it becomes easier (but not easy) to experience the Way again.

When you read samurai writings, this experience is what they attempt to capture, knowing that it cannot be put into words.

Bushido, in all its forms, underpins much of Japanese thought, and underneath Bushido sits Taoism, Confucianism, Zen, and Shinto. So in order to understand Japanese history, you have to understand these four philosophies. The best way to begin with Taoism is to read the Tao te Ching. It is a bedrock book–but not the only book–of Taoism. Sadly, we in the West don’t have access to many translations of Taoist writers. When you read Japanese samurai writers, they were often bilingual in Chinese and so read many different texts. Keep in mind that the Tao te Ching may appear airy and vague, but it speaks about concrete experiences and practical application. Japan’s warrior class wouldn’t be attracted to the text otherwise. When you read Miyamoto Musashi, Ekikan Kaibara, and other writers, you see they focused on the practical above all.

Ancient texts were designed to chew. They didn’t spoon feed you ideas because they wanted you to consider the variety of meanings behind their words:

Throw away holiness and wisdom, and people will be a hundred times happier. Throw away morality and justice, and people will do the right thing. Throw away industry and profit, and there won’t be any thieves.

They also seek to shock you into thought. Throw away holiness and wisdom? Why? Because if you follow the Way, you won’t need these things. You will already be holy and wise without those labels and preconceptions getting in the way of the practice. Throw away morality and justice? If society was structured to follow the Way, such ideas won’t be needed because they would be the people’s nature. Behind these societal ideas is a directive toward you, the reader, too. Don’t strive to be wise or holy. Don’t strive to be moral and just. Be them all by practicing them until the actions are automatic. While you practice, you will notice they are natural to your soul. I’m tempted, here, to go into a Judeo-Christian rabbit-hole, but I will refrain.

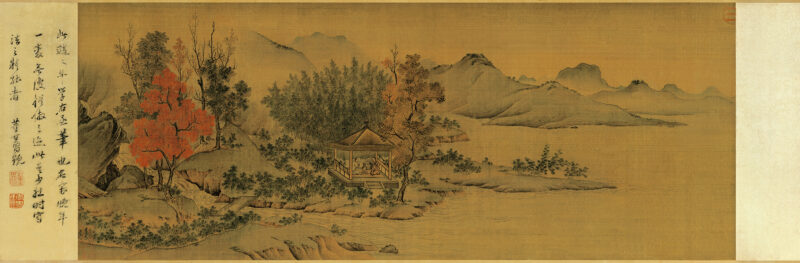

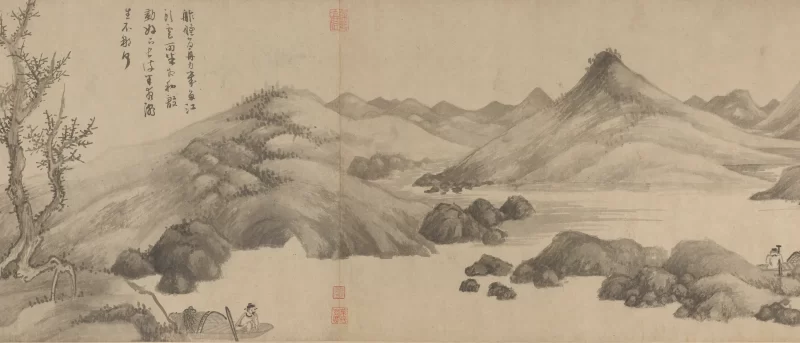

If you want to dive deeper into Japanese culture, you also need to understand Chinese philosophies like Taoism. During the Heian period, Japan adopted many Chinese practices and ways of thinking, and these became the underpinnings of later Japanese culture.

When I was younger, I rode a couple of horses fairly regularly. A good horse has a personality of its own. And a good rider leaves slack in the reigns, leaning just slightly in the saddle… she urges a direction, but allows that the horse will figure out the details. I always thought riding was a good example of Tao. Life is a dance.

This is an interesting article. I’d never really considered the deeper Taoist elements to reading Miyamoto Musashi, with whom I’m most familiar. But it does make sense, especially in light of the books of “Water” , “Wind” , and “Void”, and the overall theme of “Go Rin no Sho”. Musashi was, if nothing else, an accepting pragmatist.

With regard to contemporary Western interpretations of Bushido, much appears founded in the rather Christian-influenced (Religious Society of Friends) writings of Inazō Nitobe. The earlier Nationalist-Imperial versions for domestic consumption, built on those earlier almost death-cult like values would probably strike most Westerners as at least disconcerting, if not outright offensive. Nitobe, I think, rather softened and cleaned things up for Western consumption. Ironically, most in contemporary Japanese society are more familiar with the export version, which was re-introduced to post-War Japan through the efforts of people such as Mieko Kamiya and various others either associated with Japanese Christian movements, or with Nitobe. To what extent Tao played a role in Nitobe’s interpretation, I can’t say. But there’s certainly a sense of natural balance, and a validating of life when there is no point or purpose to its alternative.

I like your horse metaphor for the Tao!

Taoism hides in many Japanese writings, even in some Zen writings I’ve read. You’re right about Inazō Nitobe’s softening of Bushido. Interestingly, he appears to be drawing on the upstream writings of Yamaga Soko, Takuan Soho, Daidoji Yuzan, and others. It’s a small step to take the often-metaphoric writings about death into literal thinking. Even the mostly pro-death cult Yamamoto Tsunetomo often wrote about death as a means of awakening to life. Taoism appears throughout the upstream Bushido writings, even though Takuan wrote from a Zen perspective. I recommend reading Yamaga Soko and Takuan Soho. Takuan gets deep into the weeds of Buddhist philosophy, however.

That God has a personality is a *Christian* concept not a Jewish one. Judeo-Christions generally means Christian theology that has been “dressed up” by saying Jews believe it too which is mostly not the case. We (the Jewish people) are well aware that for God to be God, It must be “No Thing”. For if God was a person or personality then God would be limited by being “some thing”.

Maimonaides spent quite a bit of time on the subject. In “The Guide for the Perplexed Book III, Chapter 28”, Maimonides draws a distinction between “true beliefs,” which were beliefs about God that produced intellectual perfection, and “necessary beliefs,” which were conducive to improving social order. Maimonides places anthropomorphic personification statements about God in the latter class. He uses as an example the notion that God becomes “angry” with people who do wrong. In the view of Maimonides (taken from Avicenna), God does not become angry with people, as God has no human passions; but it is important for them to believe God does, so that they desist from doing wrong. [from wikipedia page on Maimonides https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maimonides ].

When Taoist say “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal. The name that can be named is not the eternal Name.” A Jew would agree. “Ehyeh asher Ehyeh” which to Christianity means “I am that I am.” But that’s not what the Hebrew says. It means something like “I am that which I am becoming.” The Christian God by their interpretation is fixed unlike the Jewish God which is ever creating Itself . God is not human. It has no motivations we can understand. As Isaiah said:

“For My plans are not your plans,

Nor are My ways your ways

—declares the LORD

But as the heavens are high above the earth,

So are My ways high above your ways

And My plans above your plans.”:

— Isaiah 58:8-9 Jewish Publication Society Tanakh [ https://www.sefaria.org/Isaiah.55.8?lang=bi&with=Navigation&lang2=en ]

The Taoists like the Jews believe there is power in the written word.

“So is the word that issues from My mouth:

It does not come back to Me unfulfilled,

But performs what I purpose,

Achieves what I sent it to do.” Isaiah 55:11 JPS Tanakh

This idea presents another possible Taoist influnce in Japan: the use of amulets for “magical power”. An anime / LN example is in “The Irregular at Magic High” where one of the secondary characters is a practitioner of “Ancient Magic” and uses various amulets to control elemental spirits.

Thank you for the detailed comment! You’ve given me information to explore.

The idea that God is static depends on the branch of Christianity you discuss. In my “flavor” of Christianity, God is the ground of existence, which is constantly creating or “I am that which I am becoming” as you quote. For me, God isn’t a static entity nor a human. God relates to us on a human level because that is what we can understand. It’s similar to how a parent relates to a child based on the child’s developmental level. So when I refer to Judeo-Christian, I refer more to my tradition. I don’t consider “I AM” static by any means. I should’ve clarified this better, perhaps. You are correct, however. Many branches of Christianity view God as a static entity and more akin to Zeus or some other Greek god than the God the Bible discusses (in both the Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament).