Under Ieyasu’s early government–the start of the Edo period– the Christian population doubled from about 150,000 to 300,000. It was also the only period (from about 1598-1614) when a Roman Catholic bishop was allowed to reside in Japan. But scandals and various events I covered in this article shifted policy toward deportation and eventually execution as the government felt threatened by Christian lords. The government worried about colonization by the armies of Spain and Portugal. The Shogun was well aware of how the armies followed the first missionaries in the New World. They also feared popular uprisings inspired by Christians. These fears didn’t reflect the reality of Christianity of the time, however. Missionaries in Japan had little to do with the armies of Spain and Portugal, and they conformed to the rules set by the Shogunate. Christian thought at the time also didn’t want to disrupt the governmental order (Yukihiro, 1996). But these fact did little to ease the fears of the Shogunate.

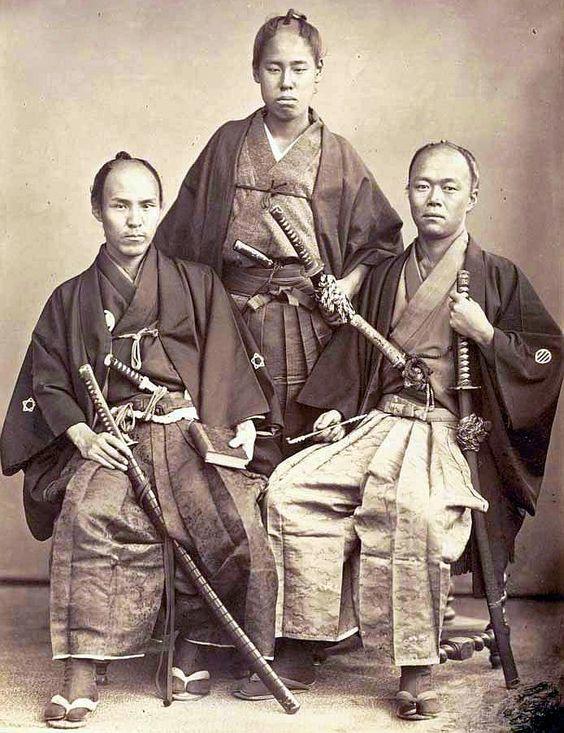

Christian executions picked up in substantial numbers around 1620. Before then, the government focused on the samurai class. One such samurai was Adam Arakawa, the Christian leader of Amakusa, who was executed in 1614 (Kaiser, 1996). I’ll list some of the major execution events.

- In 1622, 21 missionaries and 34 lay people were decapitated and burned at the stake.

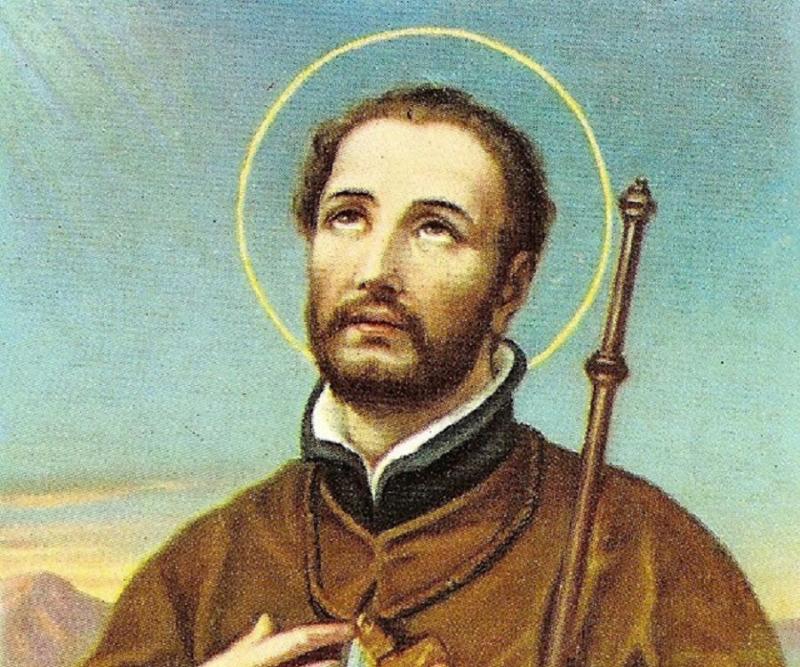

- The Great Martyrdom of Edo in 1623 saw 50 people killed, including the Jesuit Girolamo de Angelis and the Franciscan Francisco Galvez.

- In 1623, at least 60 people died in Takoku, including Diogo Carvalho. They were sent to Sendai prison nude. All of them froze to death.

Among the government’s many inquisitors, Mizuno Morinobu was most known for his cruelty. More than 300 people died by his orders, many thrown into the boiling hot spring at Unzen (Hur, 2007). Despite these incidents, the government didn’t fully set out to kill the low-class Christians. That is, until events in the regions of Shimabara and Amakusa.

The Shimabara Rebellion erupted in 1637 as a result of these persecutions, taxation, and general discontent among the peasants and ronin, masterless samurai, of the region. Led by Amakusa Shiro, the uprising shook the Shogunate enough that the government raised an army of over 120,000 soldiers. The rebellion ended about 6 months after the rebellion began. Amakusa Shiro was executed. The rebellion had a lot more to it, but covering the rebellion would require more space than I have to spare in this article. But the most important fact to keep in mind: the Shimabara Rebellion made the Shogunate realize the danger of Christian peasant rebellions and began to crack down on Christians across all classes.

Two years after the failure of the Shimabara Rebellion, the once-quiet region of Amakusa rebelled (Yukihiro, 1996). As you can imagine, the Shogun wasn’t pleased and set about the total eradication of Christianity. In 1639, only 150,000 Christians lived in Japan, from the high of around 300,000. When Japan opened to the rest of the world, an estimated 40,000 Christians were discovered in the 1860s (Breen & Williams, 1996).

The Jesuit Inquisitor

Cristorias Ferreira (in Japan between 1609-1650) was a high-ranked Jesuit, and he became the first apostate in 1633. As an apostate, he became one of the main inquisitors of the Shogunate. The torture that broke him involved being trussed and hung upside down in excrement. After he converted to Zen Buddhism, took on the name Sawano Chuan, and married a Japanese woman, he had a hand in executing and breaking several of his former brethren. Several Jesuits attempted to save him from his apostasy. The first group that tried to save him died in prison after he captured them. He handed the second group over to the same man that broke his faith, Inoue Masashige. Masashige forced this group of Jesuits to apostatize as well, and they lived out the rest of their lives in prison (Hur, 2007). The events of the novel and movie Silence are based on this.

How to Spot a Christian

In response, the Christian community rejected martyrdom in order to survive. The yearly denial of their faith created a dilemma that shaped their beliefs. Over time, the Virgin Mary was elevated into the Trinity, taking on the role of the Holy Spirit (Breen & Williams, 1996; Kentaro, 2003):

…only a mother figure, limitless in her compassion, could understand the anguish caused by denial and, moreover, forgive it.

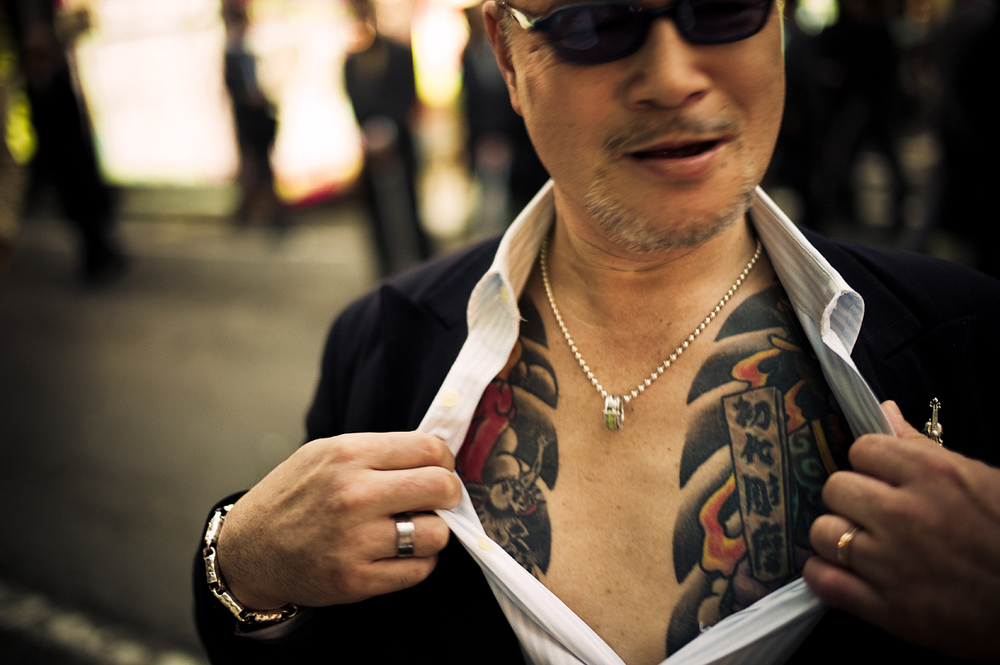

Of course, the Shogunate knew this test, called efumi, wouldn’t be enough. A spy system known as the 5-family group developed. This system grouped 5 households together, making them mutually responsible for helping each other…and spying on each other. If a member of the group denounced a family within the group as Christian, the other 4 families were free of suspicion. But if someone outside of the group accused a member, all members of the 5 families were executed (Mullins, 2003). In 1687, the government began watching the families of martyrs for Christian activity, requiring the families to submit written notices for births, deaths, marriages, moving, change of name, and other family events.

And to make sure the government didn’t miss anyone, it forced everyone to undergo a Buddhist funeral. This made sure that any Christians they missed would become Buddhist when they were laid to rest.

References

Breen, John (1996) “Accommodating the alien: Okuni Takamasa and the religion of the Lord of Heaven.” Religion in Japan. Cambridge: University Press.

Breen, John & Williams, Mark (1996) Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. MacMillan Press: New York.

Offman, Michael. (2014) Christian missionaries find Japan a tough nut to crack. The Japan Times. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/12/20/national/history/christian-missionaries-find-japan-tough-nut-crack/

Hur, Nam-lin. (2007) “Death and Social Order in Tokugawa Japan.” Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Kaiser, Stefan. (1996) “Translations of Christian Terminology into Japanese 16-19th Centuries: Problems and Solutions.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

Kentaro, Miyazaki (2003) “The Kakure Kirishitan Tradition.” Handbook of Christianity in Japan. Boston: Koninklyke & Brill.

Mullins, Mark. (2003) Handbook of Christianity in Japan. Boston: Koninklyke & Brill.

Nosco, Peter (1996) “Keeping the faith: bakuhan policy toward relgions in seventeenth-century Japan.”Religion in Japan: Arrows to Heaven and Earth. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Turnbull, Stephen (1996) “Aculturation among the Kakure Kirishitan: Some Conclusions from the Tenchi Hajimari no Koto.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

Yukihiro, Ohashi (1996) “New Perspectives on the Early Tokugawa Persecution.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

Great article! Really appreciate the scholarship involved. Will check-out the novel, “Silence”

Thank you! The film is also interesting.