After Japan was unified under Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and finished with Tokugawa Ieyasu, the Tokugawa government declared there would be no more wars. The final war is a two-part rebellion of Christian samurai, farmers, and other impoverished people. The second part of the rebellion remains the best remembered because of how it ended in a massacre of starving civilians and marked the end of war for close to 250 years.

As is usual for Japanese history, events tangle in complicated ways. The first part of the Amakusa Rebellion happened between 1589-1590. The rebellion involved the Christian samurai who lived in the Amakusa Islands as the final act of a rebellion that started in Higo province. The rebellion of Higo province began in 1587, so for the sake of simplicity, lets call the revolt the Higo-Amakusa Rebellion and declare it ran from 1587-1590. The final rebellion, sometimes called the Shimabara Rebellion or the Shimazu Rebellion (1637-1638), erupted because the underlying causes of the Higo-Amakusa Rebellion weren’t solved.

The Higo-Amakusa Rebellion was led by kunishu, also called kokujin or “people of the province.” These were local warriors who owned some land and villages. They were roughly equivalent to the barons or lords of medieval Europe. Their domains were more a feudal confederacy than the lands of the daimyo who served Hideyoshi, and kunishu domains lacked the centralized control of these daimyo. During the unification process, Higo became a battlefield for the Shimazu, the Otomo, and the Ryuzoji, with the barons splintering into various voluntary and forced alliances with these larger powers.

The Higo-Amakusa Rebellion triggered when Hideyoshi defeated the Shimazu in 1587. He left the Shimazu in control of Satsuma and Osumi provinces and left the Osumi provinces under control of the Otomo (quite generous of him!). He assigned other daimyo to the provinces of Kyushu. Trouble began when Hideyoshi moved Sassa Narimasa to Higo province. Worried that Sassa would end their independence, the kokujin began to resist Sassa’s efforts to survey the province. In a few weeks, the armed resistance ignited across the province, forcing Hideyoshi to send Kato Kiyomasa and several other generals to the province. Shimazu Yoshihiro also moved in to quell the unrest, but his entry into the province (remember, this is soon after the Shimazu fought in Higo) sparked even more ire among the kukojin.

Because of his failures, Sassa Narimasa was ordered to kill himself in 1588.

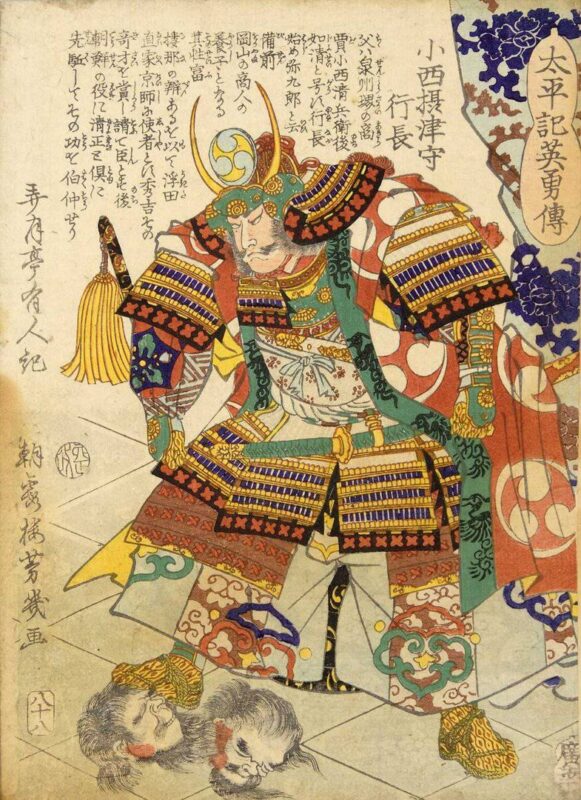

Hideyoshi eventually divided the province between two generals: Kato Kiyomasa, and his closest general, Konishi Yukinaga–who’s Christian name was Konishi Augustin. So far, the barons of the Amakusa Islands hadn’t involved themselves outside of disobeying Sassa’s orders to send troops to help put down the rebellion. They also ignored Hideyoshi’s edict to expel Jesuit missionaries.

A Little About Konishi

Let’s take a moment for an aside. Konishi Augustin numbered among the most powerful Christian daimyo. The son of a merchant, Konishi’s merchant connections and abilities as a general allowed him to serve both Oda Nobunga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Konishi also had ties with Hibiya Kudo’s family, who received Francis Xavier when the Jesuit visited. Konishi would later marry one of his daughters into the Hibiya family. So, Konishi and his family had deep ties with Japanese Christianity. Despite this, Konishi and his father numbered among Hideyoshi’s most trusted men.

The Amakusa Enter the Higo Rebellion

In September 1589, Konishi ordered the Amakusa barons to provide labor to build his castle at Uto. The barons argued that it was a private work by a neighbor and not a public work ordered by Hideyoshi, which they would undertake. Konishi used the refusal as an excuse to send troops against the baron Juan Shiki Rinsen, who was among the number of barons who refused to provide labor.

The troops were massacred in a trap. This prompted Hideyoshi to order Konishi and Kato to bring the Amakusa islanders under their control with Juan Shiki’s castle as the main objective. Juan Shiki asked for help from his fellow barons. Andreas Amakusa Tanemoto sent his best general, Giorgio Kiyama Danjo with 500 soldiers. Kata Kiyomasa encountered them and, in a rare event, fought Danjo in single combat and killed him. After receiving no more reinforcements, Juan Shiki fled his castle.

Konishi was left by Kato to handle the aftermath of the siege of Shiki. Kato marched along the coast toward Hondo castle. The castle presented desperate defense, forcing Konishi to bring his reinforcements to help Kato in his assault. The fall of the castle was described by Luis Frois and described in his History of Japan. He noted even the women of the castle fought:

In order to fight freely and without any hindrance, as one they cut off their hair,and so that their long kimonos would not get in the way they discretely tied up the hems. Certain of them put on armour, others wore swords at their belts, others too had spears, still others had various weapons about their persons, and in addition to armour they had rosaries and reliquaries hanging round their necks.

Of the 300 women who fought, only 2 survived with severe wounds.

Meanwhile, on Kato’s request, Konishi attacked the back gate of the castle. He delayed his assault to allow the Christian defenders time to escape, and, perhaps, even arranged an evacuation according to Frois, because of his shared beliefs with the people. Frois stated 1,000 Christians survived thanks to Konishi. While the numbers may be suspect, there is a letter sent by Hideyoshi that suggests Frois may not have been exaggerating even if his numbers had been inflated:

The circumstances concerning the fall of Shiki Castle have been reported to me, it was done speedily as you were ordered and I believe it to be an outstanding feat. In the matter of Shiki there was clemency shown, the wives and children without exception were led by Yukinaga to the neighbouring district and other people were substituted in this castle.

Konishi showed mercy during the siege of Shiki Castle, but that act of mercy left him at odds with Kato.

Konishi remained in the Amakusa Islands to arrange a peaceful settlement. He took the islands as his own fief, with Hideyoshi’s blessing. Juan Shiki Rinsen was allowed to return and many of the other barons also submitted peacefully. Under Konishi’s consolidation, the Amakusa Islands became a Christian area. By the year 1600, over 200 churches were built on the Amakusa Islands. The islands also had a college for training priests and even a printing press in the castle town of Kawachi no Ura.

As I mentioned, Konishi ended up on the losing side of Sekigahara where he was captured and executed. Kato had sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu and conquered the still-loyal-to-Konishi Amakusa Islands. During the conquest, Kato showed similar mercy and generosity toward his enemies, allowing the people of Uto Castle to go free in return for Konishi’s son-in-law’s suicide. Both Kato and Konishi were copying Hideyoshi’s show of mercy in the past, such as his generous dealings with the Shimazu.

When Christian suppression became national policy, the second Amakusa Rebellion ignited. This one ended with the last stand and massacre at Hara Castle. This war was said to have been the final war until the Tokugawa period’s ending.

The Final Rebellion

It’s a bit misleading to call the second Amakusa Rebellion the final one. During the Tokugawa period, there were many other rebellions, but these were more localized. Likewise, the Tokugawa fought wars against the Ainu to the north. But the age of wide-scale war and rebellion ended with Hara Castle. You can consider this rebellion as an extension of the original Higo-Amakusa Rebellion because the lingering problems weren’t solved: namely the poverty and crackdown on the Christian population.

The rebellion involved the Shimabara province and the Amakusa Islands. The rebels even raised a teenage messsiah as their figurehead: Jerome Amakusa Shiro, the son of an underground Christian preacher. The fall of Hara Castle, the Amakusa stronghold marked the end the rebellion. A few accounts of the time made it to us:

Among [the defenders] were four or five hundred bowsmen able to hit evne the eye of a needle, and some eight hundred musketeers that would not miss a board or a hare on the run, nor even a bird in flight. On earthen parapets they set up catapults to hurl stones at the approaching enemy. Even the women had their tasks apportioned to them: they were to prepare glowing hot sand and with great ladles cast it upon the attackers, and also to boil water seething hot and pour it upon them.

Hara Castle resisted attacks for 6 weeks. During the final assault in April 1638, the Tokugawa forces massacred the weak, starving men, women, and children within the castle and burned the castle to the ground.

The rebellion gave the Tokugawa a reason to finally and totally crackdown on Christianity even though some high-ranked samurai agreed poverty and deprivation were the true cause of the uprising:

When talking at Edo Castle about the cause of the riot, the chief retainer of the Omura Clan, Hikoemon, was asked whether Christians habitually had such uprisings. Hikoemon said that he doubted the insurrection was because of Christians:

“During the civil war era,” [he said], “there were many Christian lords, but they never started riots. To tell the truth, I am now 70 years old, but I was once a Christian soldiers myself.

The massacre of Hara Castle ended wide-scale war until the Meiji Restoration. It also marked the end of open Christian practices in Japan, driving Christianity underground. Often in history, unresolved roots grow into future conflicts, such as these two rebellions. Sometimes these links can be hard to see when they are separated by decades and even centuries. For example, we are still dealing with the problems caused by the Age of Colonization back in the 1700-1800s. The arbitrary countries created during that age have led to various conflicts because of the artificial way the map joined together peoples with centuries of warfare between them.

The Higo-Amakusa Rebellion and the Shimabara Rebellion have roots in poverty, autocracy, and deprivation caused by years of war. It takes a long time for an area to recover from war. Christianity acts as both a cause and a scapegoat for Hideyoshi and for the Tokugawa government. History is a chain of cause and effect, where effects become causes themselves. While in the middle of this chain, we often can’t see how everything interconnects. Even with a few centuries distance, some tangles, such as the interplay of personalities, values, and other factors leading into these rebellions and the final massacre at Hara Castle, can be difficult to tease out. The lesson for today is for us to reserve judgment on current events until we have more information and distance from those events.

References

Clements, Jonathan (2010) A Brief History of the Samurai. London: Constable & Robinson Ltd.

Turnbull, Stephen (2013) The ghosts of Amakusa: localised opposition to contralised control in Higo Province, 1589-1590, Japan Forum 25(2).

The Warring States period left such a leadership and administrative mess that starving farmers emerging from generations of essentially having to defend themselves were a ready army for anyone who arrived with the promise of something better. In many ways, the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion parallels the Ikkō-ikki movement centered around Buddhist leadership in the Osaka/Nagoya region about 50-years earlier. And personally, I suspect that Christian influences had already well seeped into Jōdo Shinshū by the latter 1500s, introducing Catholic-like traditions while substituting faith in the Amida Buddha for that in Jesus. Ironically, I think it was this challenge of faith replacing fealty to Japan’s Daimyo that ultimately united them in a fight against militant and separatist religious groups.

I need to research the Ikkō-ikki movement more. It’s interesting that Amida Buddha became the stand-in for Jesus among the hidden Christians. Your idea of Christianity’s influence on Jōdo Shinshū needs more research too. From the little I know (as I said, I need to research more), there seems to be some influence.

I should make it clear that I’m merely among those who have a strong suspicion that Shin Buddhist thought emerged from some syncretic influences. However, most who practice Jōdo Shinshū will fairly bristle at the suggestion. Curiously, however, both share a focus on salvation through faith, reverence for a “savior” of souls (Amida vs Jesus), the “Pure Land” vs a “Heavenly Kingdom”, transcendence of one’s karma vs divine forgiveness of sin, recitations, and an appeal to eschatology. There’s even a sort of spiritual triumvirate.

Shin emerged long before Catholicism and later Protestant influences arrived in Japan. However, by the 1100s, Manichaeism had been spreading through China for at least 600 years and had become a significant influence. A Persian version of the Middle Eastern savior religions, it incorporated both Jesus as well as Buddhist thought first communicated by Ashokan monks who had been dispatched to the Middle East 200-years before the time of Jesus. There’s also documented contact between the movements So while Jōdo Shinshū claims its own place, I can’t help but think that the timing of its emergence, traditions, and its curiously like-minded approach to Christian-like faith were more than mere coincidence. And much of this lends to how Christianity was so easily able to disguise itself by merging into certain Buddhist practices and iconography.

Yes, the parallels of Pure Land Buddhism and early Christianity is interesting. The apostle Thomas was said to have disappeared in India, so if true, it’s possible his influence spread to Pure Land ideas and later, to Jodo Shinshu. There’s some evidence supporting this fusion of Buddhism and Christianity with statues and what could’ve been churches scattered throughout the old Silk Road areas.

Christianity and Judaism doesn’t like the idea of Zoroastrianism influencing them either, but history is tangled and messy.