The Jomon Period is the era before writing that extends from the late Pleistocene to 410 BCE. Little is known about the religious and daily life of the earliest Japanese peoples. But they left us with the best-studied and oldest ceramic sequences in the world. Some of the oldest dates to around 15,000 years ago (Craig, 2013; Pearson, 2006). Most of what we know of the Jomon has been teased from this pottery, remains of their settlements, and the few graves we’ve discovered. Jomon pottery predates farming (appearing around 8,000 BCE in China), showing how pottery is a hunter-gatherer invention instead of an invention of farming cultures as originally thought (Craig, 2013; Pearson, 2006).

The Jomon Period is divided into 6 sub-periods (Perason, 2006; Habu, 1996):

| Sub-period | Date BCE |

| Incipient | 13,680-9250 |

| Initial | 9250-5300 |

| Early | 5300-3360/3500 |

| Middle | 3360/3500 – 2580/2510 |

| Late | 2580/2510 -1260/1230/1220 |

| Final | 1260/1230/1220 – 410 |

The dates are hazy because they mostly come from radiocarbon dating methods. They use volcanic ash layers as a foundation and also date any char that remains on potsherds from cooking. Using this, the changes in pottery and tools can then be ordered. For perspective, I like to link dates like this (which can be abstract) to history elsewhere in the world. Around 4500 BCE saw the rise of the Mesopotamian civilization. Somewhere around 4435-3200 BCE Predynastic Egypt appeared, and by 1481 BCE the Pharaoh Thutmosis III was born. Alexander the Great was born in 356 BCE. The Jomon Period stretched across all of these events.

Jomon culture changed across these periods and across the regions of Japan, but for the most part, society existed upon hunting, gathering, fishing, and some small-scale gardening or farming (Crawford, 2008; Habu, 1996). Evidence for buckwheat, millet, and other early crops have been found in some Jomon settlements, but the primary food source remained a seasonable variety. During winter, they hunted deer and wild boar. During summer, they fished and collected shellfish. They also ate chestnuts, walnuts, and acorns (Habu, 1996). Crawford (2008) suggests the wide available of tree nuts across the settlements we’ve found suggest the Jomon cultivated, or at least encouraged, the growth of the trees.

Historians disagree about the nature of Jomon villages. Evidence suggests some regions were fully sedentary. That is, the people lived in the same area all year. Other regions suggest seasonal settlements; the people traveled to different settlements based on seasonal food sources (Pearson, 2006; Habu, 1996). The oldest year-round village is found in Southern Kyushu and dates to about 12,800 BP. BP stands for “before the present era,” and is used in radiocarbon dating. It simply means about 12,800 years ago. So this village dates to the Incipient Period, the very beginning. However, Sanai Maruyama has a settlement that dates between the Early and Middle Periods. The village has more than 500 pit-homes, longhouses, raised-floor buildings, grave pits, and middens. This village appears to reach its population peak by the Final Period. The peaks of population vary based on region. Chubu and Kanto saw their population peak during the Middle Period before declining (Habu, 1996). Most Jomon settlements were arranged in a horse-shoe shape.

Jomon Beliefs and Beads

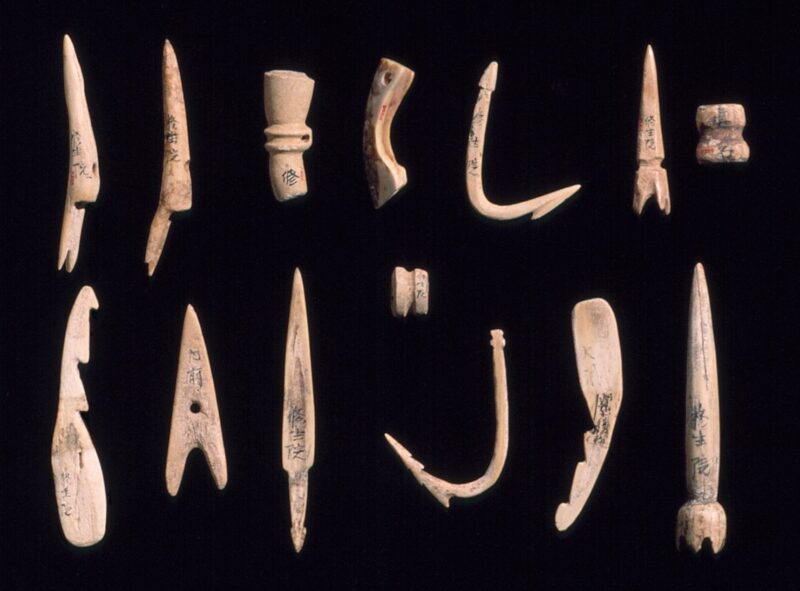

We know nothing about Jomon beliefs. They didn’t leave a written record. While artifacts like beads, figurines, pendants, and other items have been found in graves, we don’t know their significance. Aside from their pottery, the Jomon people are known for their magatama, a comma-shaped stone bead. Magatama appear early in Jomon history in small quantities before becoming commonplace by the Late Period. The beads became rare ritual and status objects during the Yayoi (300/410 BCE – 250 CE) and Kofun (250 CE – 538 CE) periods. Magatama even became a part of the Imperial Regalia (Nishimura, 2018).

The beads were designed to hang as a single pendant, as a chain necklace, or as a bracelet interspaced with other types of beads. Some researchers think the beads were linked with the magical powers of animals, the moon, or the soul (Nishimura, 2018):

Representative accounts treat the magatama shape as emulating a bear- or wolf-fang, fish or fish-hook, animal liver,crescent moon,constellation,or fetus,spirit,or soul.As well as suggesting a specific referent for the magatama symbol, these accounts explore connections with beliefs in the magical powers of symbolically-represented animals, the moon or the celestial world, or the soul and spirit. Non-representational accounts suggest that the meaning of magatama is not patterned after any specific shape, but that people may use magatama for specific purposes, such as to possess their magical powers, contact and pacify gods and the dead, exorcise evil spirits, restore youth, pray for a safe journey or good harvest, or securely attach the soul to the body.

Until the Late Period, they are found in homes. During the Early Period, they appear to be household objects, but by the Late Period, when they become grave goods, the beads appear to belong to individuals. They don’t appear to be related to social status, family, or anything else. Rather, they seem to be associated with the person. The beads are also found embedded in pots, dishes, pounders, scrapers, spoons, arrowheads, axes, weights, stone rods, and figurines. The abundance of the beads suggests by the Late Period, people had a relatively comfortable material culture, allowing people at all society levels to enjoy jewelry and other goods (Nishimura, 2018).

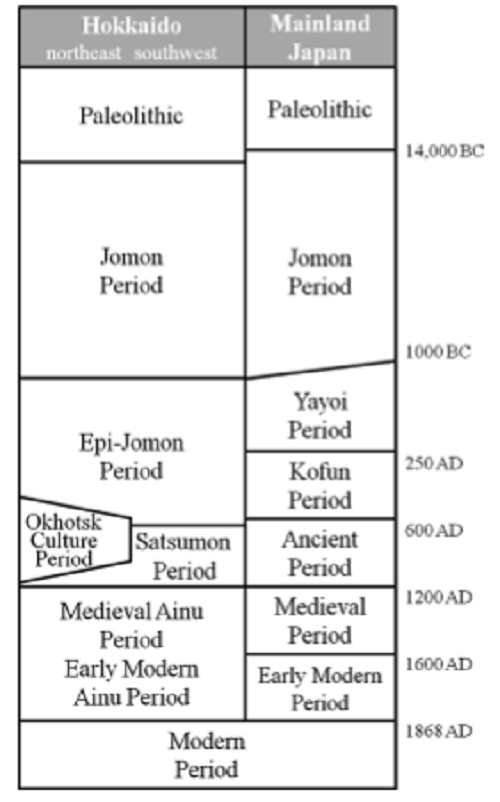

The Ainu’s Timeline

So where were the Ainu through this period? The Ainu are Japan’s indigenous people. Well, the Ainu followed a similar course as the Jomon people until they diverged in the Yayoi Period. The Ainu lived in Hokkaido, the southern part of Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands. While the Jomon adopted agriculture, the Ainu kept to the earlier Jomon ways until they moved away from the Jomon-pattern settlements in the Satsumon period. During this time, they traded with the mainland for iron tools and other goods (Onishi, 2014). It stands to reason that the Ainu traded with the Jomon throughout the periods.

As you can see from the above diagram, mainland Japan and the Ainu split after the widespread adoption of focused agriculture during the Yayoi Period. Keep in mind that this wouldn’t be a knife-cut division. It would have been a gradual process. For much of recorded Japanese history the lands of the Ainu were seen as a frontier, a wild area. The interaction between the Ainu and the Jomon in history stands as a point of contention. When historians discuss the Jomon, Ainu culture and development remains absent. The development of agriculture among the Jomon and the “failure” of the Ainu to do so suggests an inferiority in Ainu culture by contrast (Habu, 1996):

Many Japanese archaeologists interpret the complexity of Jomon culture from the perspective of long-term cultural evolution and suggest that the high level of complexity of the Jomon culture facilitated the adoption of rice cultivation and other advanced techniques from mainland Asia at the beginning of the Yayoi period.

Others disagree because rice cultivation developed in China long before it appeared in Japan, around the Initial Jomon period. But the implication against the Ainu stands. Crawford (2018) points out this problem:

An unfortunate subtext of establishing what is central to the archaeology of the Japanese nation is that the peoples of the north east and extreme south west, the Ainu and their Satsumon ancestors as well as the Ryukyu Islanders including Okinawans, are marginalized in terms of their contribution not only to Japanese history, but also to archaeological discourse in general. This perspective is not unusual in Japanese archaeology, a subject that is still grounded in writing a history of the Japanese nation that, until 1997, was officially ethnically homogeneous.

The evidence we have of the Jomon Period reminds us that Japan has always been a patchwork of, though similar in culture, regions with their own practices and habits. Different areas of Japan today still have their own unique festivals, building habits, cooking, and other regional differences. The Jomon settlements we’ve uncovered show similar signs of small differences, such as when they reached their peak of population. While we can’t know, I surmise each region had the same types of differences in practices we see in Japan today. More work needs to be done to trace the contributions of the Ainu and other groups on the earliest history of Japan. There’s much to discover from the 13,000 year stretch we call the Jomon Period.

References

Craig, O. E., Saul, H., Lucquin, A., Nishida, Y., Taché, K., Clarke, L., Thompson, A., Altoft, D. T., Uchiyama, J., Ajimoto, M., Gibbs, K., Isaksson, S., Heron, C. P., & Jordan, P. (2013). Earliest evidence for the use of pottery. Nature, 496(7445), 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12109

Crawford, G. (2008). The Jomon in early agriculture discourse: issues arising from Matsui, Kanehara and Pearson. World Archaeology, 40(4), 445. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438240802451181

Habu, J. (1996). Jomon sedentism and intersite variability: Collectors of the early Jomon Moroiso phase in Japan. Arctic Anthropology, 33(2), 38.

Ōnishi, H. (2014). The Formation of the Ainu Cultural Landscape: Landscape Shift in a Hunter-Gatherer Society in the Northern Part of the Japanese Archipelago. Journal of World Prehistory, 27(3/4), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-014-9080-2

Nishimura, Yoko. (2018). The Evolution of Curved Beads (Magatama 勾玉/曲玉) in Jōmon Period Japan and the Development of Individual Ownership. Asian Perspectives: Journal of Archeology for Asia & the Pacific, 57(1), 105–158. https://doi.org/10.1353/asi.2018.0004

Pearson, R. (2006). Jomon hot spot: increasing sedentism in south-western Japan in the Incipient Jomon (14,000–9250 cal. bc) and Earliest Jomon (9250–5300 cal. bc) periods. World Archaeology, 38(2), 239. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438240600693976

This was great, thanks for the research and writing. I think a lot of historical narrative suffers from the same thing as you’ve outlined here: the majority and current culture owns the story, and controls how its told. You see it in the Balkans a lot, and even in the US where we conveniently don’t teach major events of genocide committed by and on our own people in the last 200 years.

I wonder what we can learn about the language of the Jomon, if its even possible to have any knowledge of how they spoke. Linguistics often tells us a lot about history where material culture fails to…materialize. I also wonder what Japanese archeology says about the Korean origins of the majority of their population – is this even openly addressed by the status quo?

The migration of people across the globe, especially during pre-history, is a fascinating topic. If people understood those times better, I’d hope that they would be less tied to harmony-disrupting ideas such as rights to land based on one’s ethnicity, a concept which itself is now understood to be cultural and not static.

My point is that its not just the Japanese that are guilty of choosing which ancient evidence to highlight in order to reinforce current power structures. In fact I would argue that this is in fact the norm in all sciences, and I do not believe my viewpoint is cynical. Rather I think its subconscious in most cases, and should be expected, especially in the study of human history. Scientists are, after all, human, and therefore incapable of pure objectivity. Where it concerns history, I suspect this subtle bias toward current authoritative structures is likely magnified during the analysis of discoveries. Maybe I am cynical.

I didn’t see anything about the Jomon language while I dug through the research. Likely, it will require a fluent understanding of Japanese to dig into that.

I remember seeing an NHK piece that briefly touch upon Korean migration as an origin for many Japanese people, but it didn’t go into much detail.

You are right about the human element inside of science and historical research. Fortunately, science is designed to remove human bias over time, even if such bias can never be fully removed. Arguably, bias is necessary for objectivity because objectivity itself is a bias! After all, what defines objectivity except the biased-human mind? Likewise, pure objectivity can miss important cultural data that biased stories can reveal.