World War II marks a dramatic shift in Japanese history, equal in impact to the Meiji Restoration on the culture. The proverbs I will discuss trace deep into Japan’s cultural views of women and to the Confucian influence China had on Japanese culture. Women’s roles and freedom varied across the different eras of Japan, and some proverbs seem to trace to this differing periods. Periods are not separate to each other. They influence and build upon the culture, and proverbs capture the shifting perspective of the common people. The meaning behind many of the following proverbs may not sit well. It’s important to engage with history from history’s context, not our own perspective. Sometimes what appears from our modern perspective (and every generation considers their view as modern) as backward were progressive for the period.

A fan in autumn.

There’s no need for a fan in autumn. This proverb often refers to a divorced or deserted woman. The proverb is harsh, but it also suggests she will see her season return.

Beautiful women are unfortunate.

Beauty can be a danger. It can lead people to make assumptions about you that aren’t true. Beauty can also lead women to doubt they are loved and respected for who their inner persons are. Beauty brings its own self-image problems, confidence issues, and other problems.

Though a beautiful woman does not say anything, she cannot be hidden.

A beautiful woman stands out, even when she doesn’t want to. This and the previous proverb take a sinister turn when you put them into the Warring States period of Japan and other violent periods. Beautiful women became war prizes in such instances.

A lotus flower in the mud.

This proverb refers to a woman who keeps her chastity and character despite a morally unhealthy environment. Lotus imagery associate closely with Buddhism. A lotus flower becomes beautiful because of the mud while not falling into the mud. So too a woman becomes of strong character because of the challenges of her surroundings.

A conference by the wellside.

Before phones and running water, the village well served as a common meeting area. Women, who were typically responsible for gathering the day’s water, would gather at the well and gossip and talk. Because gathering water was a regular routine, you can imagine most of the village women meeting at the same time.

Cherry blossoms in the recesses of a mountain.

This proverb describes beautiful women who grow up isolated or are otherwise unknown. It also refers to how their beauty will fade quickly before it is noticed, like the fleeting cherry blossoms hidden in a mountain area.

When the mirror is foggy the heart is cloudy.

In various periods of Japanese history, a woman’s chastity was symbolized by a polished metal mirror. Mirrors were prized. So a mirror that was foggy plays into a double meaning. First, the mirror wasn’t cared for, showing how its owner is neglectful. This refers to a woman who failed to polish her character. Second, mirrors had supernatural associations. In some folktales, a mirror could review the true self. So, a fogged mirror reflected a cloudy, troubled soul.

Unlike the singing cicadas, the silent fireflies burn themselves.

When a woman is deep in love and remains silent, her desire can consume her like a fire. Anime and manga romances like this theme, but it has deep roots in Japanese history. Women often married young, usually in arranged marriages. So this proverb refers to wives who love someone but are unable to acknowledge their feelings.

The disagreements of women give birth to the wars of men.

Many proverbs like this one paint women in a dim light: as troublemakers, manipulators, and other negative stereotypes. However, you can also read this proverb with an eye to history. Women may be mostly silent in historical records, but they still influenced history behind the scenes. Perhaps the best example of this is Kitanomandokoro, Hideyoshi’s wife.

A woman’s wisdom is at the end of her nose.

Many proverbs serve as variations of this one, referring to women’s wisdom as monkey-wisdom and other derogatory metaphors. This proverb suggests that women are intuitive and impulsive but not wise. Proverbs like these offer a historical outlook, but we also don’t know how many people actually believed in proverbs like this one. Japanese literature often holds women up as sources of wisdom, but then there’s just as many stories that follow proverbs like this one.

A woman’s will power will pierce even a rock.

On the opposite end of the previous proverb, we have this one. Will power and discipline was honored, especially among the samurai. So saying women’s will power could pierce a rock recognizes a virtue.

Don’t give you heart over to a woman, even though she has borne you seven children.

This refers to a Buddhist doctrine that characterizes women as lustful and lecherous. It’s a warning not to trust women completely. Proverbs like this, grounded in some branches of Buddhism, may have been ignored by most. I haven’t encountered this general attitude in the literature and folktales I’ve read: villains and supernatural women don’t really count. I decided to include this proverb here because it points toward the lusty girls we often see in anime and manga stories. This character type extends all the way back to India and Buddhism.

A harlot with sincerity and a square egg do not exist.

This serves as a warning for men who frequented the pleasure districts of Japan. Those areas sold a dream, a lie. The proverb hides the cost of that dream women paid, however.

Women with fellow-women.

In the past, Japanese culture saw women as different from men in sentiments and abilities. So, many thought women should be educated and associate with other women. This proverb served as an argument against coeducation.

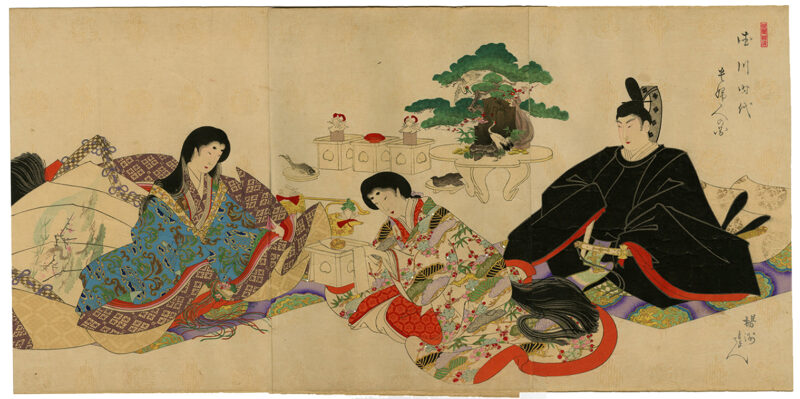

Seen at night, seen at a distance, or under a paper umbrella.

These three instances were thought to be when women appear at their most beautiful. In literature you will often find scenes of women in these three circumstances, with the moon being the most popular. You can also find all three together. In Heian literature, men like Genji were sometimes depicted in circumstances similar to these.

Further Thoughts

Many of these proverbs–and many more in the collection I referenced them from–take a poor view of women. What’s interesting is how these ideas have held on. You can find these negative stereotypes alive and well online and within anime and manga in some cases. Chastity among women wasn’t always considered a virtue in Japan’s history. Some eras allowed trial periods for marriages. If things didn’t work out–usually complications between the wife and the mother-in-law–the marriage ended and the wife returned home without any stigma attached to her. Proverbs often pass to us from multiple time periods, and each time period had different values. Some proverbs appear to be a reaction to a previous time period.

References

Buchanan, Daniel Crump (1965) Japanese Proverbs and Sayings. University of Oklahoma Press.