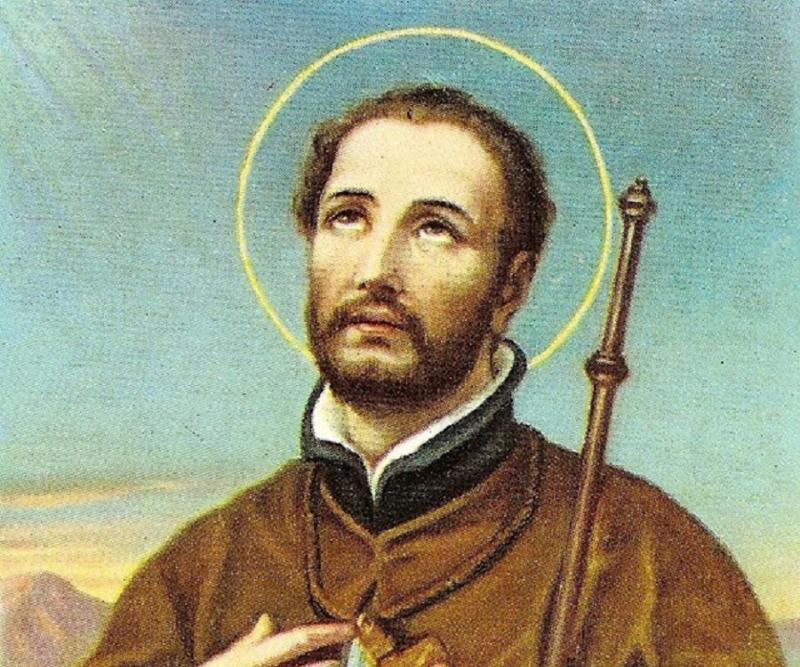

The people whom we have met so far, are the best who have as yet been discovered, and it seems to me that we shall never find among heathens another race to equal the Japanese. They are a people of very good manners, good in general, and not malicious.

–Francis Xavier c. 1551

Note: This is the first of a three-part series. The series was originally posted as a single long article.

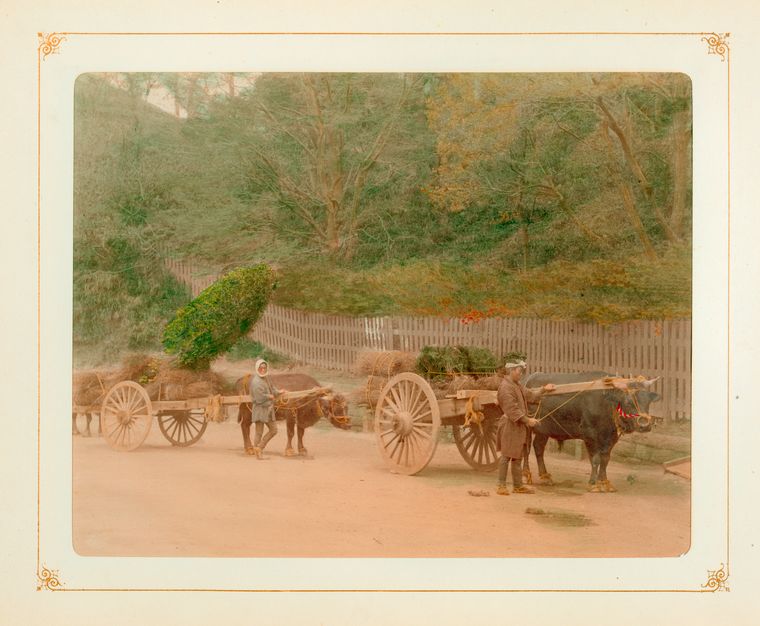

Today less than 1% of Japan’s population are Christian. In the beginning of the 1600s, 1.5% of Japan were Christians (Offman, 2014; Breen & Williams 1996). Christianity has struggled to spread within Japan, and it has had a troubled history. It all began in 1549 when Francis Xavier and Yajiro, a Japanese man Xavier met in Malacca, landed in Kagoshima. Two years later, he abandoned Japan to focus on China, leaving the country in the hands of his colleagues Allessandro Valignano and Matteo Ricci. All three decided to change the policies that had devastated the New World–the eradication of the native religions. Instead, they held Chinese and Japanese culture in such high esteem that they tried to accommodate rather than exterminate (Hur, 2007).

Japanese-Christian Terminology

…bateran sectarians by their free choice, are of the lower classes, shall be unmolested, this being a matter of Eight sects or Nine sects.

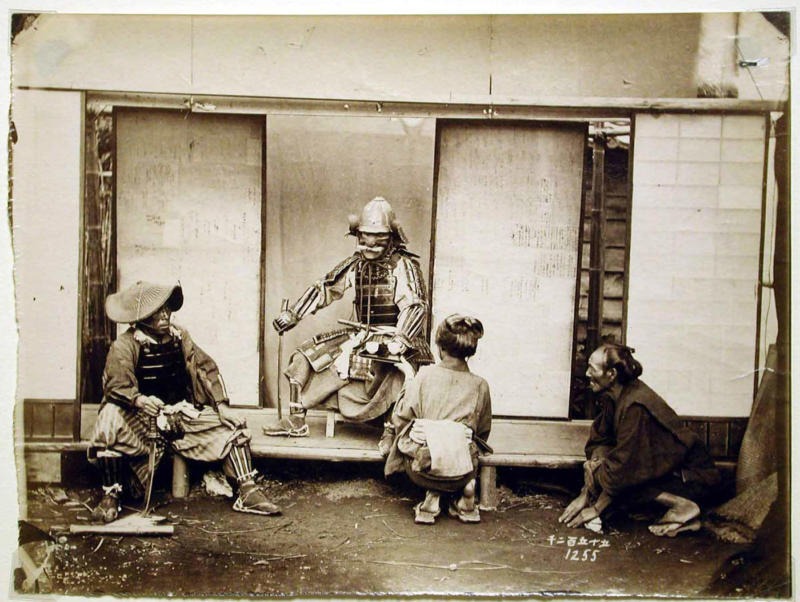

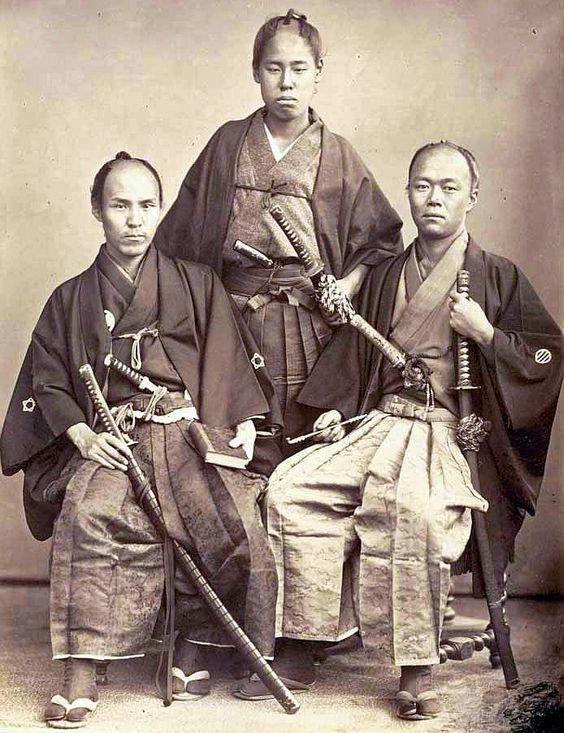

Bateran, here is used to encompass all classes, but we already see a distinction. Over time, the term bateran comes to refer to the upper classes exclusively. In 1638, an edit by Iemitsu was the first time Kirishitan was used to refer to lower-class, lay Christians (Hur, 2007). Now, this seems a little odd. However, the peasant population typically bowed to the desires of their local lords. When their lords converted, many samurai and lower-class people did as well. This, later, causes problems as Yukihiro (1996) explains:

Christianity was accommodated by the populace owed much to its readiness to acknowledge the authority of government in secular matters. Caught in a dilemma between a desire to practice Christianity on one hand, and a reluctance to rebel–for such was the nature of their faith–on the other, Christians had no choice but to recant or to go underground.

By targeting bateran, the Tokugawa government could force this problem on the lower-classes, making many recant. This is why the distinction in terms matters. However, by 1638, the government decided to extend its reach to the rest of the population. For my purpose, I won’t use bateran or Kirishitan in this article. However, I wanted to mention these terms because they are important in the academic literature you may encounter in your own research. For the sake of readability, I’ll just use Christian even though Kirishitan identify as their own branch of Christianity (Kentaro, 2003).

Yajiri, the Translator

The language barrier limited Xavier’s success, but it prompted the Jesuits to create dictionaries and found a school to teach incoming missionaries the language and culture. Valignano started the school at Sakaguchi, and he even urged missionaries to live like the Japanese people they taught. Valignano wrote a manual in 1581 about proper manners, the proper way to eat, the proper way to dress, and even covered architecture for church buildings. It was something of a textbook for the school (Mullins, 2003). Because of the problems Xavier and Yajiro faced with word substitutions, the Jesuits and the Spanish Franciscans took to using Japanese transliterations of Portuguese and Latin terms. But otherwise, they translated prayers and passages in popular language to make them accessible. Sanctos no gosaguyo no uchi nukigaki, printed in 1591 is an example of this. It contains extracts from the Acts of the Apostles, but written in popular language (Kaiser, 1996).

However, this wasn’t to be. Later Protestant incursion after Japan opened its borders in the late 19th century found few surviving references to Portuguese traditions. Christianity, during the closed Tokugawa period all but disappeared.

Christianity under Tokugawa Ieyasu

Under Ieyasu’s government, the Christian population doubled from about 150,000 to 300,000. It was also the only period (from about 1598-1614) when a Roman Catholic bishop was allowed to reside in Japan. Ieyasu’s tolerance of the religion was a part of his plans to develop a trade network that connected Japan with Manila and New Spain (Mexico). The Franciscan order, at first, helped him establish these connections. The missionary Jeromino de Jesus Castro had official permission to teach in Edo and establish a church in 1599. In return, trade from Portugal and Spain entered Japan. It’s unclear how well Ieyasu understood Christianity. He, like many others at the time, likely thought it was a branch of Buddhism (Nosco, 1996; Hur, 2007).

However, soon a scandal that reached right into Ieyasu’s home fired his suspicions toward Christianity, leading him to reverse his tolerance and begin the age of expulsion. Under Ieyasu, even after the scandal, didn’t execute Christians (Nosco, 1996).

The event known as the Okamoto Scandal of 1612 began back in 1608 with a clash in Macao between the crew of the Christian vessel of the daimyo Arima Harunobu (1567-1612) and Portuguese sailors. Sixty Japanese died in the clash. A few years later the Portuguese vessel, captained by Andre Pesoa, returned. When Harunobu heard of this, he appealed to Ieyasu for permission to avenge the 60 slain Japanese. This sort of grudge holding was common for the samurai class, even its Christian members. Seeing his chance, Harunobu and the Nagaski magistrate attacked Pesoa for 4 days, eventually sinking the vessel and all of her crew. The scandal begins after these events, which while they would strain relations between the Shogunate and Portugal, wouldn’t have been too off base from Japanese customs at the time.

However, Harunobu and his co-commander Hasegawa Fujihiro believed they should’ve been rewarded for their good deed of defending Japanese honor. The retainer Okamoto Daihashi saw an opportunity and made the two believe he was lobbying for a reward. In return, Harunobu and Fujihiro offered him the usual bribes. Daihashi then forges a letter from Ieyasu, a serious crime. Well, this goes on for a time before Harunobu decided to speak with Daihashi’s lord Honda Masazumi about why the land transfer was taking so long. Of course, Masazumi had no idea a land transfer was happening and launched an investigation that ended with Daihashi being burned at the stake for his forgery.

The scandal should’ve ended there, but Harunobu and Fujihiro, who was a shogunal deputy of Nagasaki, clashed over the mistaken reward. Harunobu tried to murder Fujihiro, which was an attack on the shogunate itself. Harunobu was ordered to commit seppuku, and an investigation was launched. The investigation revealed how Christianity has spread throughout the ruling class and even among Ieyasu’s personal bodyguards. It also discovered a conspiracy to undermine the shogunate.The investigation ended with the exile of 26 Christian vassals (Hur, 2007).

This convoluted scandal turned Ieyasu against Christians. In a letter, Ieyasu laid out his resistance to Christianity by grounding his government in a pledge toward the gods and buddhas (Hur, 2007):

Since the creation, [the Japanese people] have worshiped kami and revered the Buddha. The Buddha and kami are like…traces of each other, identical and not different. The matters of solidifying loyalty and righteousness between the lord and vassals, of ensuring no perfidy, and of building up a strong nation in unity are all pledged to the kami. This is the proof of mutual trust.

Ieyasu’s statement laid the groundwork for the persecutions to come. In response, the Society of Jesus attempted to bride lords to reverse the policy. Under their pressure, a Portuguese trade ship refused to unload its Chinese silk, causing a jump in prices. But their brides and trade threats didn’t move the government–Christian deportations increased (Hur, 2007). This set the stage for the next phase of the government’s policy toward Christians.

References

Breen, John (1996) “Accommodating the alien: Okuni Takamasa and the religion of the Lord of Heaven.” Religion in Japan. Cambridge: University Press.

Breen, John & Williams, Mark (1996) Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. MacMillan Press: New York.

Offman, Michael. (2014) Christian missionaries find Japan a tough nut to crack. The Japan Times. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/12/20/national/history/christian-missionaries-find-japan-tough-nut-crack/

Hur, Nam-lin. (2007) “Death and Social Order in Tokugawa Japan.” Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Kaiser, Stefan. (1996) “Translations of Christian Terminology into Japanese 16-19th Centuries: Problems and Solutions.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

Kentaro, Miyazaki (2003) “The Kakure Kirishitan Tradition.” Handbook of Christianity in Japan. Boston: Koninklyke & Brill.

Mullins, Mark. (2003) Handbook of Christianity in Japan. Boston: Koninklyke & Brill.

Nosco, Peter (1996) “Keeping the faith: bakuhan policy toward relgions in seventeenth-century Japan.”Religion in Japan: Arrows to Heaven and Earth. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Turnbull, Stephen (1996) “Aculturation among the Kakure Kirishitan: Some Conclusions from the Tenchi Hajimari no Koto.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

Yukihiro, Ohashi (1996) “New Perspectives on the Early Tokugawa Persecution.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

そういや景教が平安か奈良か其れ以前に日本に伝わったって聞いたことがあるな

It is possible Nestorian Christians were in Japan before Francis Xavier. After all, Nestorian Christians were in China, and Prince Shotoku seems to have had a Nestorian advisor. However, this branch of Christianity doesn’t seem to have spread like the Jesuit/Catholic branch did.

Great article Chris. As someone who is interested in East Asia and religion in general (in a sociological/historical way as I don’t consider myself religious or even spiritual), I found this thoughtful and well-sourced intro really useful. Sorry in advance about the upcoming short essay but I think you might find this interesting to know. So the comment of Nestorians in Japan: Scholars seem to be in a consensus that there’s no conclusive evidence that Nestorians were in Japan before the Jesuits (at least in any organized way). One scholar has stated that “…there is no evidence that Nestorians missionaries were ever active in Japan.” (Wilmshurst p.169). Same scholar is also doubtful about any Nestorian presence in Japan during the Mongol period, much less a religiously organized one (Ibid. p. 170).

Another writer also lays out the information that there was very likely not an organized presence of Nestorians in Japan and even reports of so-called Nestorian artifacts said to be in Japan are of dubious reliability. The veracity of a Nestorian advisor to Prince Shotoku are similarly dubious. (Moffett p. 459-460).

Even among scholars that are sympathetic to the inconclusive claim of a Nestorian advisor in ancient Japan or other Christians in pre-16th century Japan, they still admit that there’s little to no evidence of a continuous or organized effort and that these contacts can only be called possibilities. See (Gilman & Klimkeit p. 360-361) and (Baum & Winkler p. 65).

TL;DR – No good evidence of any organized presence of Nestorians in Japan exists, reports of Nestorian artifacts or influence are dubious, a general Nestorian presence in pre-16th century Japan are inconclusive at best, and the Jesuits are the earliest organized Christian community in Japan in the 16th century. Again, sorry about the essay but I just wanted to chime in and let other possible readers or lurkers know what some of the literature says about the subject. I also hope everyone here can learn a thing or two about the fascinating subject of Christianity in Japan.

Sources:

1. Moffett, Samuel (1998). A History of Christianity in Asia, Vol. 1: Beginnings to 1500. New York: Orbis Books

2. Wilmshurst, David (2011). The Martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing

3. Gilman, Ian; Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (1999). Christians in Asia Before 1500. London: Routledge

4. Baum, Wilhelm (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London: Routledge

Thank you for the great information! It is interesting.

Given what happened to other countries like the Americas when Christian missionaries and subsequent colonial conquest ensured, as in the extermination of local cultures and belief-systems that resulted, no wonder the shogunate reacted in such a forthright manner to ensure the continual survival of Japanese culture and religion, and if they hadn’t, no doubt Japanese culture and religion would have been likewise demolished and would not have survived today.

The possibility of Japanese culture’s destruction was real. However, in the writings of early Christian missionaries, Japanese culture was held up as a superior culture that would create a “superb” Christian nation. I don’t believe Japan would have shared the fate of the Americas, but the culture would certainly be different without Shinto and Buddhism, although I suspect Japanese Christianity would have fused with Zen Buddhism in interesting ways. It is a fun thought experiment, at the least.

What a callous and cruel comment that reveals the biases of modern, secular westerners.

Christians were a 10% minority population (300-500k). Is there any other event in human history where you support the eradication of a 10% minority population? Tell me one besides Japan, because you justify it here.

I’d also agree with Chris that the colonialism argument is invalid. The persecutions continued AFTER the foreigners were kicked out, and Japan had a large, well armed military even by the 16th century. Couldn’t be conquered.

Christian civilians were dipped upside down into piles of human excrement with their temples cut so they wouldn’t pass out. This was one of many torture mechanisms to eliminate the faith from society. Worse of all was torture of civilians if a different civilian wouldn’t apostatize (leave the faith).

Torturing innocent people to make you give up your faith places a Christian in a harder spot than any other method. If you allow the torture to continue, you violate Jesus’s teachings. If you apostatize, you also violate Jesus’s teachings. This is especially true if the torturers kept their word and stopped after Christians denounced their faith. I can see why Japan’s Christians became hidden. Publicly they would denounce their faith while inwardly keeping it to spare others from torture.