Ask most English speakers about what makes Japanese so hard to learn and you will most likely hear kanji. The Japanese writing system consists of kana, or a phonetic script, and kanji, which are pictorial symbols Japan inherited and adopted from China. During the Meiji Restoration (beginning around 1868 following the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate period), intellectuals and statesmen aimed at modernizing and reforming the entirety of Japan so the country could stand up to and stand beside the nations of the period. Japan sent people all over the world to learn about different approaches to government, finance, military, and so on. The Japanese language itself came under scrutiny for reform. Many thinkers worried that the complexity of the language and the immense time and effort literacy took would hold Japan back. The military soon ran into real problems thanks to the unwieldy nature of the language during the Sino-Japanese War in 1894 and the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 (Takatori, n.d.):

[F]irst because the number of kanji had become too large to memorize without an exceptional effort, and second because the assignment of sounds to kana had become so archaic that they no longer reflected pronunciations then current in the language. The average fighting man, having received only an elementary-level education, was not a master of kanji, much less a student of historical spelling, and therefore the likelihood that he would misunderstand written instructions, or worse, fail to execute orders, if such were composed in traditional text, was intolerably high.

The number of kanji made it difficult for soldiers to sort machine parts, perform repairs on Japan’s newly modernized equipment, and other tasks. The military realized something drastic had to be done as Japan became a colonial power.

Back in the governmental and academic spaces, four movements arose. The first aimed at simplifying and systematizing kana and kanji. The second wanted to eliminate kanji and convert kana into a phonetic alphabet. The third movement, which also favored moving to the Roman alphabet, proposed adopting English as Japan’s official language. And the fourth wanted to write Japanese using the Roman alphabet.

Simplifying Kanji

While a small faction, the group that wanted to keep kanji and kana around would eventually win the tussle. They created the version of Japanese people use today. The movement, called kanbun kundokutai aimed at simplifying kanji from its 80,000 or so phrases down to more-manageable numbers. The aim was to make kanji flex between meaning and phoneme so it could expand to hold all the new Western ideas that were entering Japan. The system still proved more complex and daunting for the less-literate than Roman alphabet proposals. But print media backed this system, and it presented a simpler writing system than in the past (Ueda, 2021):

Newspapers were one of the primary media that did much to foster the popularity of kanbun kundokutai, not only as the dominant style used in newspaper reports and columns, but also as a means to disseminate many translations of scholarly works, not to mention the newly established laws and declarations.

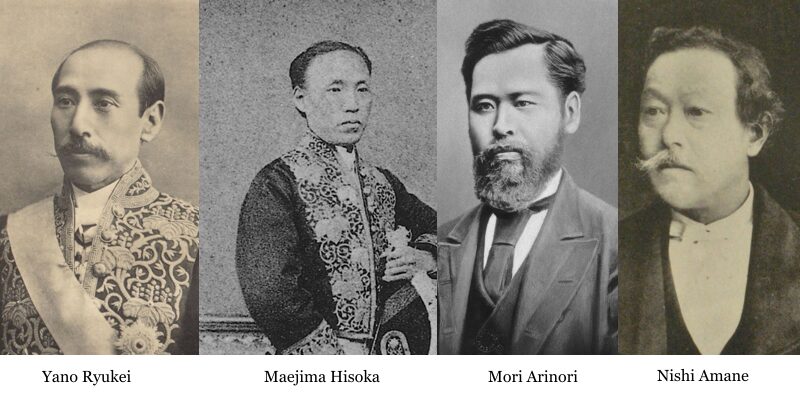

Yano Ryukei, an author and a journalist, argued for reducing kanji to 3,000 characters from the 80,000 or so kanji that existed during his time for popular use. He claimed most kanji were from classical literature and so obsolete. The system proved to be a middle ground. However, the military still found it too cumbersome. The War Ministry became directly involved in the language debate, proposing various options for all the different factions, while favoring the Roman Alphabet factions above the kanji and kana factions. By 1942–which shows just how long the language reform debates continued–the War Ministry proposed reducing kanji to 500 or 600 characters. Today, Japanese still uses around 4 times that number (Takatori, n.d.).

The public eventually supported the simplification faction, which still used kana, because of how the print industry backed it. It was an improvement over the older system. Japan’s literary world saw this system as a compromise. It valued the old writing system. By 1908 all books were published with the simplified system. The new compromise still created a gap between the “literate” and the rest of the population. Kanji supporters argued that the system allowed the most meaning to be seen in the smallest amount of time. Kanji could “more concisely and economically pass along necessary information than kana or the Roman alphabet” (Ueda, 2021).

Within this movement, and overlapping with all the others, was a push to eliminate the different dialects for a single dialect: Tokyo’s. Ueda Kazutoshi, a Japanese language scholar, wished to “exterminate” dialects by imposing Tokyogo, the Tokyo dialect, over the entire country. He argued that a national language was the “spiritual lifeblood” of Japan and a requirement for it to unite and compete with the West. Politicians also pushed for this, but schools resisted the effort through 1931. Schools even promoted dialects, calling them the “wild grass that grows naturally in this fine pasture called national language” (Laanien, 2018). The effort to create a single dialect eventually failed despite the rest of the unifying movement succeeding.

The Plan to Kill Kanji

I am in support of any group that seeks to abolish kanji, whatever conjugation system said group advocates in promoting kana. I will support any group with the most people. Actually, I will support any group—whether the Tsuki or the Yuki factions, whether advocates of kana or the Roman alphabet—as long as they seek to abolish kanji. I will not hesitate to give my support. There is nothing I hate more than kanji these days.

–Toyama Masakazu (1848–1900): writer, sociologist and the teacher of Inazo Nitobe.

Despite losing the reform movement, the plans to kill kanji remain interesting and might even be relevant for Japan’s future as its population declines. I will touch on this later. For now, let’s look into the movements to end kanji. There were many reasons why Meiji Restorationists wanted to end kanji. Some had nationalistic motivations. They viewed kanji as archaic in the face of Western writing systems. Others saw kanji as too Chinese at a time when anti-Chinese sentiments were rising. They wanted a purely Japanese writing system. Still others wanted a system that would be easy to learn for everyone in their country.

Kana as an Alphabet

The first anti-kanji movement wanted to eliminate kanji for a kana-based alphabet system. Many of the Roman alphabet proponents also favored a kana-based alphabet system. They saw kanji as a matter of national security. Kanji would hinder Japan’s progress on the world political stage. Maejima Hisoka was a statesman and founded Japan’s postal system. He wanted kana to become a phonetic, indigenous alphabet to produce “a language that, once uttered becomes spoken language (danwa) and once written becomes written language (bunsho)” (Ueda, 2021). He equated kana with the Roman alphabet and wanted to make hiragana the national writing system:

When we rely on old methods of education by using kanji, or even when we change the methods of education but use kanji, kanji would not only be trying for students’ brains (shin’nō) and interfere with their intellect, but would also interfere with the development of the students’ physical constitution (taishitsu) and weaken their physical frame (taikaku). There would be no hope to equal the physically and intellectually well-equipped people of Euro-America.

Maeijima’s mention of physical constitution refers to Japan’s old education system, called Sodoku. Under this system, students would repeat texts until they were memorized without understanding the meaning of the words they spoke. The practice required physical posture to be a part of the memorization process: legs bent at 60 degrees with feet on the floor, sitting with lower back only slightly touching the back of the chair, knees at a right angle, body tilted slightly forward, chest puffed out and 13 more details for sitting and standing learning. The idea was the entire body “consumed the text of recitation” (Ueda, 2021). Maejima saw all of this as a waste of time. He wanted a language and learning system that would increase understanding by unifying phonetics with word meaning, which was what the old kanji system failed to do. Maeijima Hisoka argued that “by abolishing kanji from the education of the public, we will reduce the amount of time spent on reading and writing, that is to say, on memorizing the pronunciation and figures of ideographs.”

Kanji learning, in other words, focused too much on the means of conveying ideas and content and not enough time on those ideas and content. This also served as one of the arguments for the Roman alphabet movement.

Adopting the Roman Alphabet

Even before the Meiji period, scholars of Dutch studies, the Tokugawa period phrase for Western learning, viewed the Roman alphabet as superior to kanji. The Roman Alphabet, also called the Latin Alphabet, is the writing system English, Spanish, and other Western languages use. It’s mostly a phonetic system. Although Mori Arinori, the founder of Japan’s modern education system, argued that it was a partially hieroglyphic writing system because English still used silent letters to spell words like though. Mori favored dropping the Japanese language altogether for simplified English. He proposed dropping all silent letters from English and standardizing all irregular words. So though would be spelled tho. Saw would become seed. Spoke would become speaked. He placed more value in spoken language than on written language, wanting the written to match what was said. In a 1872 letter Mori wrote in English to William Whitney, an American linguist at Yale, Mori explained why he thought English was best for Japan (Ueda, 2021):

The spoken language of Japan being inadequate to the growing necessities of the people of that Empire, and too poor to be made, by phonetic alphabet, sufficiently useful as a written language, the idea prevails among us that, if we would keep pace with the age, we must adopt a copious and expanding European language. The necessity for this arises mainly out of the fact that Japan is a commercial nation; and also that, if we do not adopt a language like that of the English, which is quite predominant in Asia, as well as elsewhere in the commercial world, the progress of Japanese civilization is evidently impossible. Indeed a new language is demanded by the whole Empire…. All the schools the Empire has had, for many centuries, have been Chinese; and, strange to state, we have had no schools nor books, in our own language for educational purposes. These Chinese schools, being now regarded not only as useless, but as a great drawback to our progress, are in the steady progress of extinction…. The only course to be taken, to secure the desired end, is to start anew, by first turning the spoken language into a properly written form, based on a pure phonetic principle. It is contemplated that Roman letters should be adopted… It may be well to add, in this connection, that the written language now in use in Japan, has little or no relation to the spoken language, but is mainly hieroglyphie—a deranged Chinese, blended in Japanese, all the letters of which are themselves of Chinese origin.

Like the other reformers, Mori didn’t favor English because of an infatuation with the West. Rather, he had a distinct nativist and nationalist motivation. Mori represents the anti-Chinese sentiment that ran through the anti-kanji movements. Mori wanted to get away from kanji. He wanted to turn the “spoken language of Japan” into a written form “based on pure phonetic principles.” Mori stood in his own camp while still supporting those who favored the Roman alphabet, such as Nanbu Yoshikazu and Nishi Amane.

Nanbu Yoshikazu wanted to get rid of “inconvenient kanji” for the Roman alphabet so that “the new language could be understood whether it was heard or seen.” Nanbu wrote (Ueda, 2021):

In order to change the script and establish grammar, we must first decipher the correct sound (oto o tadasu) and designate appropriate script. Our country has fifty sounds, in fact, seventy-five including voiced consonants (dakuon), and all words are produced with these sounds. As such, we must first of all identify the correct sounds; in order to do so we must designate appropriate scripts to them.

He favored the Roman alphabet over kana because vowels and consonants were separate, creating more convenience and flexibility than kana has. Kana folds vowels and consonants together: か, ka, for example. Kana scripts need to be “improvised” when representing “contracted sounds” like kya (2 kana characters) and voiced sounds like da だ and “ga” が which require additional glyphs on the phoneme to transform the sound. The Roman alphabet doesn’t need to do this (although it does use some compounds for sounds like ch and sh) and solves other problems, Nanbu explains. He wanted the use the Roman alphabet to present the 50-sound syllabary in a simple, systematized way. He would later carry this goal to the kana faction.

Nishi Amane, a philosopher and political advisor who served in the Ministry of War, the Ministry of Education, and other areas, agreed with Nanbu. Nishi wanted speaking and writing to follow the same rules. Mori would’ve seen Nishi’s proposals has “hieroglyphic” because he wanted to retain Japanese’s silent letters in word spellings. Mori favored dropping all non-phonetic parts of writing. Both Nishi and Nanbu prioritize written word over spoken.

Many other politicians were in favor of adopting romaji as we now call this Roman alphabet system. The Japanese military wanted to use the Roman alphabet because, even with simplification, kanji and kana continued to pose logistical problems (Takatori, n.d.). At first, the military favored James Curtis Hepburn’s system, created for English speakers who were learning Japanese, before favoring Nipponsiki. Nipponsiki was created by Tanakadate Aikitu as a counter to the Hepburn system. The army’s Land Survey Division adopted Nipponsiki in 1917. The Navy started using the system for some maps in 1922. Eventually, the government settled on a compromise between Hepburn and Nipponsiki that favored Nipponsiki. This writing system was called Kunrei.

The Importance of the Written Word

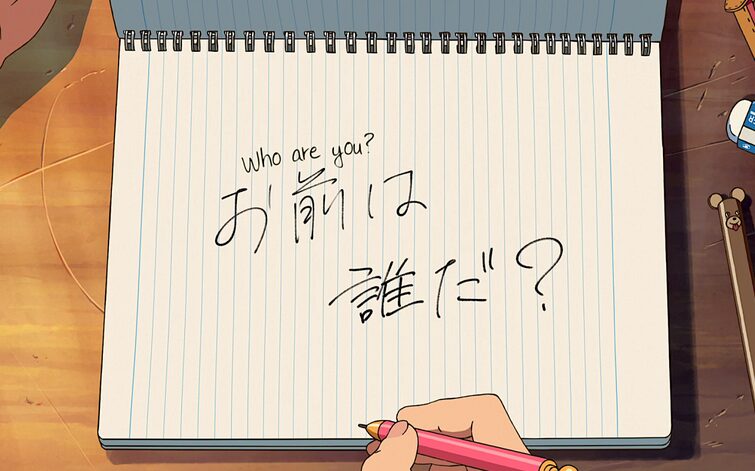

The tangle I sketch–and I’ve simplified this tangle–continues today. Kanji has grown in number and kana is split between hiragana and katakana. While kanji hasn’t approached the 80,000 characters used in the past, it is still far higher than the number the Japanese army wanted back in 1942: around 500 characters. So why didn’t the Meiji effort to simplify the writing system work? The compromise that retained kana and kanji did simplify Japanese compared to the past, but it failed to reach the goals the founder of Japan’s modern education system wanted or even want the military deemed best–adopting the Roman alphabet. Takatori summarizes the reasons why the reform efforts “failed”:

Historically, the Japanese as a whole have shown little interest in devising a system which would make possible effortless and unambiguous reading or quick and simple writing. As a consequence, they have allowed the haphazard addition of kanji into their lexicon, with no long-term and persistent attempt at trimming the excess. Even today, when Westerners, stumped by enigmatic place or personal names, complain about the dreadful nature of Japanese writing, it causes the Japanese to feel secret pleasure and pride in its complexity, and a disdain for exclusively phonetic writing.

Mori and other Meji reformers were concerned that kanji would hold Japan back. These concerns proved unfounded. Japan arose to become a powerful nation and remains a world leader today. However, Japan faces a new problem: population decline. Many concerned experts are calling for the government to aim at stopping Japan’s population decline at 80 million. At the current rates, the country may hit 63 million people by 2100, which is half of Japan’s population in 2023 (Yokota, 2024). Many reasons sit behind Japan’s population decline, including Japan’s immigration policies. But kanji is also a factor. The US’s National Security Agency Japanese ranks as one of the most difficult languages for English speakers to learn. The difficulty of the written language poses a barrier for immigration. If Japanese use the Roman alphabet, this would ease the written language barrier for all nationalities that use the Roman alphabet. The population decline poses a reduction in military personnel, so kanji again impacts military operations, if indirectly. As Japan’s population and world standing falls, language reform may again become a debate, along with immigration policy. Mori’s concern about kanji holding the country back may become a salient point. Even if kanji ends up abolished in the future, kanji and kana will remain relevant for art and literature. Japan has a rich literary history which will require scholars and translators, which is needed anyway under the simplified kanji system. Calligraphy using kanji and kana will remain an art as well.

And this brings up the question of identity. Would Japan lose a piece of its identity if the writing system would change to romaji or some form of it? All the arguments I read from the Meiji period in favor of the Roman alphabet argued such a change would enhance the Japanese identity. It would allow wider access to Japanese literature and ways of thinking. Anime and manga prove the point. When they became accessible world-wide, mainly in English, their industries’ profits took off. Japanese culture and ways of thinking became more familiar, which is a form of soft power. Also consider how many cultures use the Roman alphabet. Even some tribes like the !Kung, a group of people in Southern Africa, use the Roman alphabet for their language, which includes tongue-click sounds. Native American culture was also preserved through using the Roman alphabet to transcribe their oral traditions (Granted, that was not always a matter of choice). All of these cultures remain unique and have their own unique ways of thinking despite sharing the same alphabet. None of the Meiji reformers seemed concerned about losing their heritage by jettisoning kanji. Even the kanji-simplification faction didn’t deem the reduction to be much of a loss.

It’s too soon to say if Japan will face a similar push for language reform as it had during the Meiji Restoration. But we may see such a discussion in the coming years depending on how immigration reform and population decline concerns shift.

References

Laaninen, Mark (2018). The Complexity of Modernization: How the Genbunitchi and Kokugo Movements Changed Japanese. Aisthesis.

Takatori, Yuki (n.d.) The Forgotten Script Reform: Language Policy in Japan’s Armed Forces. George State University.

Ueda, Atsuko (2021) Language, Nation, Race: Linguistic Reform in Meiji Japan (1868-1912). Oakland, California : University of California Press.

Yokota, Ai (2024) Business leaders, expert call on gov’t to stabilize Japan’s population at 80 million in 2100. The Mainichi .https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20240111/p2a/00m/0na/020000c

It’s probably inevitable. But it will only happen after the generations that have learned little more than Jōyō kanji age to the point where the cultural shift can occur. And I doubt that it will mark a prosperous era. At that point, perhaps they will be reduced to few hundred abbreviated forms, or tossed altogether for kana with a few more grammatical particles to flag kanji alternatives. And for a number of reasons, I don’t see English replacing Japanese any more than I do Esperanto.

And then there’s Taiwan…

Any time a language disappears, we are worse off for it. I’ve long wondered if the force of centralization would reduce the world’s languages to a handful of main languages and the rest would fade into academic and culture niches. We see similar forces in technology, literature, and economics. Of course, periods of centralization are usually followed by periods of fragmentation. Greek and Latin were the main languages of the Roman Empire. When the Western Empire collapsed, languages fragmented and developed into what we see today.

(´・ω・`)?

(ノ´Д`)ノ

Ironic… I just finished interpreting the traditional Chinese kanji on a probably Hong Kong Cantonese poster for someone… and no, I don’t speak Chinese. While I did have to look up a specific meaning for a compound (moth orchid), an advantage to a shared logographic writing system is that it can be used to communicate across different languages and dialects.

Also, while Japanese might be phonetically represented in an accurate manner through kana (I would resist the use of rōmaji), the language has a remarkably limited number of sounds.

As a consequence, there a lot of homophones that can become confused with one another.

“Sore wa ōkina hanadesu ne!” Did someone pick a sunflower… or was that an insult!

Even in spoken conversation, you’ll occasionally see someone turn away to draw a kanji in the air in order to more precisely make a point, express a concept, or just make something understandable. So while I can understand the impetus for simplifying the writing system, I’m not so sure that it will work for everything in Japanese.

The sources I read as I worked on this article–I didn’t reference all of them since they just confirmed the the sources I used–didn’t discuss homophones. The Meiji Restorationists didn’t mention them or seemed concerned in what I read. Mori likely would’ve used the homophone argument to support his desire to move to English as Japan’s national language. You make a good point about how Japanese and Chinese kanji can act as a bridge. My Chinese friends have told me that they hate (their word) Chinese writing and prefer English for similar reasons the Meiji writers list. I’ve been told English is “much more precise and requires less guessing.” It’s interesting that you’d mention air-drawing kanji with that context in mind. Conversations with them prompted me to go looking into Japan’s anti-kanji movement.

Japanese culture has historically internalized foreign ideas and concepts perceived to have a benefit… mirrors and metalwork, Buddhism, writing… exemplified today in “loan words” phonologically approximated with katakana. However, difficulties arise from the inconsistent way in which kanji was implemented as a means to preserve the spoken language. On one hand, Chinese character pronunciations could be used to approximate Japanese linguistic sounds or names. But then they were also applied to meanings, resulting in the “on” versus “kun” dichotomy that results in two ways to say everything. For example, the compound of “water” and the “character of a thing” can be read in onyomi as “suisei” (watery), or kunyomi as “mizushō” (a promiscuous woman). So kanji usage requires context… why kanji tattoos are a bad idea.

BTW… Perhaps exemplifying that context issue, I misinterpreted the Chinese kanji for “moth orchid” (phalaenopsis) mentioned above. My husband, who can speak Mandarin and some Cantonese, recognized the kanji as being the name, Hu Die, a famous Chinese actress from the ’30s. And my literal interpretation of “shadow star” implied a “movie star”. (The poster was an old perfume ad.)

Do you think language reform may reappear in Japan’s future as the population declines?