Baptism remained a vital part of their practice. Men assigned to be a baptizer in the local Christian community were called ojiyaku and served as the local leader. These baptizers had special purity requirements: bathing first, laundry washed separate from the rest of the family, separate wash basin, soap, and towel. Baptizers couldn’t care for cows or even hold a baby; he couldn’t be peed upon. Before baptizing someone, the ojiyaku would be doused with cold water and not dry off with a towel. Instead, his wife handed him a special baptismal kimono, no underwear allowed. He also had a special mat to keep from sitting on a tatami floor before baptizing. All of these ideas to avoid becoming polluted came from folk beliefs of the time (Kentaro, 2003).

Japanese Christian Documents and Confusion

The work begins with a version of Genesis and jumps into the New Testament. It mentions nothing of Jesus’s teachings, but it has a long Passion narrative with the Resurrection and Ascension. The long version of the book goes into the Communion of the Saints, the End of the World, and the Last Judgment. Segments of the Rosary is also found in the book along with non-canonical materials the Jesuits used to teach simple theology to new converts. For example, a short story involving Mary appears in a similar form in the “Arabic Infancy Gospel” (Turnbull, 1996):

When three days had passed, Mary asked for a bath. Then she recommended that the son of the house take a bath in the same hot water. The house-wife said, “Although I appreciate your thoughtfulness, our son is suffering from the pox, and in danger of his life. Please forgive me.” But Mary insisted he took a bath, and was suddenly cured of the pox and lived, to the great thanks of all.

Some scholars believe some of the passages and traditions may be memories of images like the pieta. For example, Mary conceives Jesus when a butterfly enters her mouth, but this could come from the memory of icons that depicted a dove flying in the background near Mary’s mouth. Time could’ve muddied the memory slightly. The book also has passages that have been localized (Turnbull, 1996):

They tied him [Jesus] up as they had been ordered and flogged him hard enough to break his bones until the bamboo rods split into pieces. They pushed various things that were bitter and hot into his mouth, and pressed an iron crown onto his head. Blood ran down from his body like a waterfall.

The book tries to explain various Japanese cultural practices. The custom of women shaving their eyebrows and blackening their teeth was thought to date from the time of Noah.

Accommodating Christianity

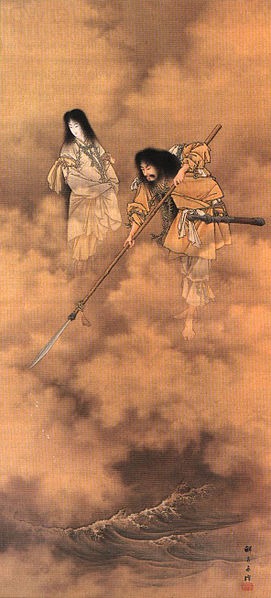

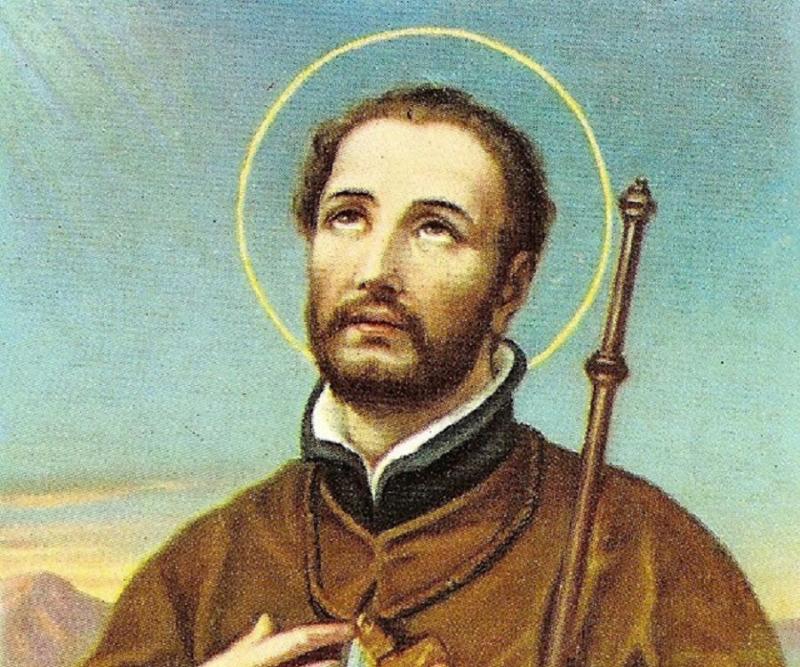

As the Tokugawa period ended and Japan opened to the rest of the world, serious thought was given to making accommodation toward Christianity. Okuni Takamasa (1792-1871) proved to be the most influential. He believed Christianity was a branch of Shintoism, if a distorted one, and while it shouldn’t be vilified, it also shouldn’t be allowed inside the center of Shintoism. The 2500th anniversary of the 1st emperor of Japan marked an epoch, according to Okuni, where Japan would become the center of a new global order centered on Shinto. He thought the Western science Japan was adopting were a legacy of Sukunahikona, one of the deities involved in the creation of the world.

Okuni examined Christianity through his Shinto beliefs and through his political beliefs. He considered the story of Genesis in the Bible as an example of spirits born from Shinto deities. Adam came from Itakeru no kami. Even Jesus, to Okuni, came from the deity Takamimusubi (Breen, 1996). He accepted Christianity and then attempted to explain it, a shift from the past rejection of the religion. However, despite his belief of accommodation, he believed Christianity had no place in Japan as a distorted branch of true Shintoism and for political reasons (Breen, 1996):

The reason for the frequent visits of foreign vessels to our shores is quite simply that they wish to disseminate throughout Japan the Christian way of friendship and love. It is a frightful prospect. It is not that Confucianism, Buddhism, and Christianity have nothing to say about the virtues of loyalty, piety, and chastity. It is simply that they dilute them. They are diluted by comparisons with loyalty, piety, and chastity here in Japan.

He goes on and writes “the headquarters of Christian religion are sited overseas; this could mean the national wealth is transported out of Japan, and the nation could suffer impoverishment as a result.” For Okuni, Christianity would dilute both Japan’s spiritual code and political welfare, but that didn’t mean he was against it. He viewed it as “a rather good religion.”

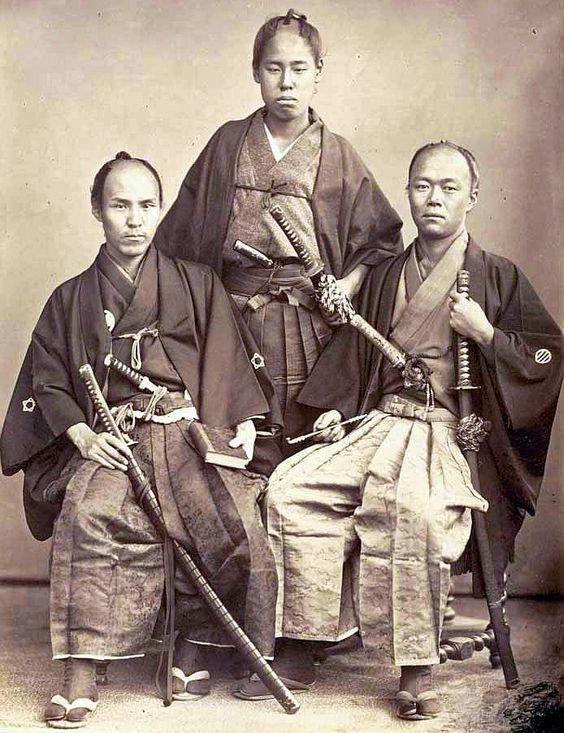

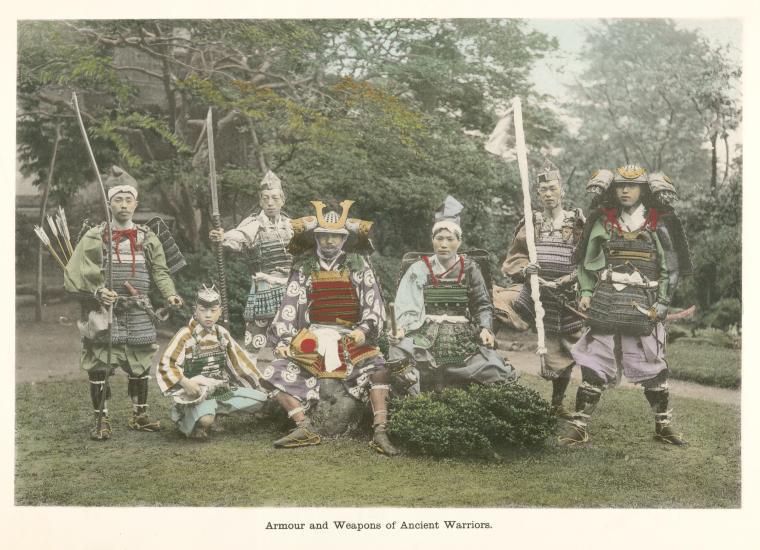

Okuni and other thinkers at the time–along with pressure from the Western powers like the United States and Britain–helped Japan move from persecution to a wary accommodation. The historical memory of Christian uprising and meddling by Christian nations remained in their thinking. However, their limited acceptance eventually allowed Japan’s hidden Christians to come out of hiding. Some groups merged with the Catholic Church, while others preferred to remain separate and continue their distinct practices. However, they no longer had to fear eradication at the hands of the samurai.

References

Breen, John (1996) “Accommodating the alien: Okuni Takamasa and the religion of the Lord of Heaven.” Religion in Japan. Cambridge: University Press.

Breen, John & Williams, Mark (1996) Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. MacMillan Press: New York.

Offman, Michael. (2014) Christian missionaries find Japan a tough nut to crack. The Japan Times. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/12/20/national/history/christian-missionaries-find-japan-tough-nut-crack/

Hur, Nam-lin. (2007) “Death and Social Order in Tokugawa Japan.” Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Kaiser, Stefan. (1996) “Translations of Christian Terminology into Japanese 16-19th Centuries: Problems and Solutions.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

Kentaro, Miyazaki (2003) “The Kakure Kirishitan Tradition.” Handbook of Christianity in Japan. Boston: Koninklyke & Brill.

Mullins, Mark. (2003) Handbook of Christianity in Japan. Boston: Koninklyke & Brill.

Nosco, Peter (1996) “Keeping the faith: bakuhan policy toward relgions in seventeenth-century Japan.”Religion in Japan: Arrows to Heaven and Earth. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Turnbull, Stephen (1996) “Aculturation among the Kakure Kirishitan: Some Conclusions from the Tenchi Hajimari no Koto.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.

Yukihiro, Ohashi (1996) “New Perspectives on the Early Tokugawa Persecution.” Japan and Christianity. Impacts and Responses. New York: MacMillan Press.