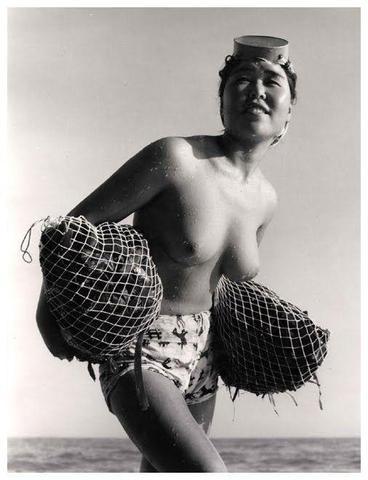

Ama come from a tradition that dates back over 2,000 years, and the tradition is dying. Today, about 2,000 ama dive off the coast of Japan, and fewer dive each year. Most ama are well into their 60s and 70s (LeBlanc, 2015; McCurry, 2016). Before we continue, I have to leave you with a disclaimer. This article contains nudity. Before the 1900s, ama dived naked except for a traditional loincloth. The earliest images of ama, naked from the waist up, appear in 18th century ukiyo-e. Ama have worn wetsuits since the 1960s (LeBlanc, 2015).

Ama come from a tradition that dates back over 2,000 years, and the tradition is dying. Today, about 2,000 ama dive off the coast of Japan, and fewer dive each year. Most ama are well into their 60s and 70s (LeBlanc, 2015; McCurry, 2016). Before we continue, I have to leave you with a disclaimer. This article contains nudity. Before the 1900s, ama dived naked except for a traditional loincloth. The earliest images of ama, naked from the waist up, appear in 18th century ukiyo-e. Ama have worn wetsuits since the 1960s (LeBlanc, 2015).

The Ama Tradition

No one knows exactly how women became deep sea divers. Westerners assume ama dived for pearls, but most dived to collect seaweed, fish, and shellfish to supplement their meals and sell on the marketplace. Ama are almost exclusively women. They dive in the cold sea without the aid of scuba gear, using only rocks to help them sink as far as 30 feet below the sea. Most traditional ama were wives of fishermen. They would dive so they can earn extra money while their husbands were away on prolonged fishing trips (Martinez, 2004; LeBlanc, 2015; Tanaka, 2016).

On Shima peninsula, ama once dominated. After World War II, 6,000 of the 10,000 total divers lived in the area. Today only 750 live there (McCurry, 2016). Ama break with Japanese culture norms, particularly the ama of Shima. Since feudal Japan, women were relegated to a limited role, based upon class. In samurai classes, women were shut off from society and were expected to manage the household and raise children. The lower classes granted women more freedom, but she was still subject to her husband. Merchant class women, for example, were expected to help manage the household and provide help with the family business. Farming class women helped plant the fields in addition to her household duties.

However, ama in the Shima area flipped these expectations. In some situations, the husband assisted her. He would wait topside for her to tug on her safety rope. Then, he would haul her up and help with her catch. During the Tokugawa period, these women were seen as strong and a match for their husbands. Many started their profession as children to continue to dive well into their 80s (LeBlanc, 2015).

When the husbands were away, ama dived in groups. Each woman would tie themselves to a wooden bucket that acted as a float. Diving in groups helped reduce danger, but whenever you dive up to 30 feet in cold water for up to 2 minutes, people can die. In a typical day, these women dive 100-150 times (Tanaka, 2016). Ama developed a culture of beliefs and practices to help reduce this danger.

Superstitions of the Ama

Ama fishing villages feature a special temple for the women to pray before heading off and their own communal warming huts for when they return from a cold day’s work. They developed their own protective symbols. The seiman, or 5-pointed star, adorn their head scarves and tools. Written in a single stroke, starting and ending at the same point, the star represents their safe return to the surface. Another design, the dohman, a lattice design that keeps danger away and represents watchfulness. Before each dive, the women knock on the side of the boat with their chisel and recite a short mantra (LeBlanc, 2015).

Ama fishing villages feature a special temple for the women to pray before heading off and their own communal warming huts for when they return from a cold day’s work. They developed their own protective symbols. The seiman, or 5-pointed star, adorn their head scarves and tools. Written in a single stroke, starting and ending at the same point, the star represents their safe return to the surface. Another design, the dohman, a lattice design that keeps danger away and represents watchfulness. Before each dive, the women knock on the side of the boat with their chisel and recite a short mantra (LeBlanc, 2015).

Men ama divers exist, but the profession is dominated by women. Diving is done relatively close to shore. While men took trips out into open waters, women could dive nearby to help the family’s income. Men would take the best boats, while women could make do with less seaworthy craft. Women were also thought to be better at diving than men. First, women have an extra layer of fat that helps them tolerate cold water better than men (LeBlanc, 2015). Women were also thought to be better able to hold their breath and for longer than men (Tanaka, 2016).

Today’s Ama

Ama is a dying profession. Several reasons go into this. First, young women don’t have any interest in learning the special breathing techniques ama have perfected. Second, the profession doesn’t pay. While their staple crop abalone can net $80.00 for 2lbs, abalone are getting harder to find due to overfishing and environmental changes (McCurry, 2016). Ama is a sustainable fishing system. It allows the diver to be selective. While the lack of nets and other gear protects the environment, oceans face pressures from industrial methods that impacts the ability of ama to find their catches. The profession may soon disappear because of these factors.

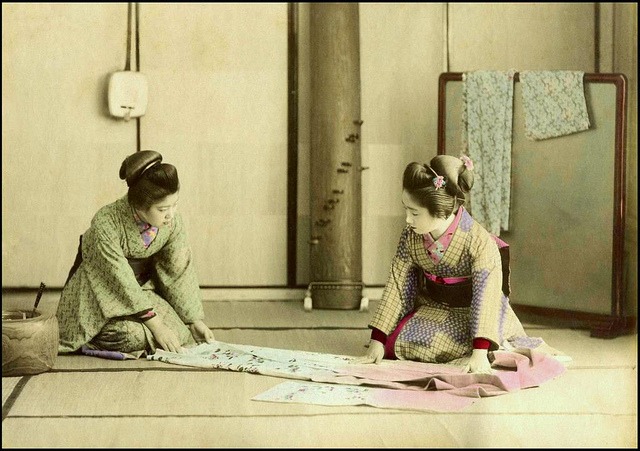

Topless Diving and the Mysterious, Exotic Orient

I have to comment on the images I chose to use. For a good portion of Japanese history, nudity among women carried little shame, particularly for the lower classes. Nudity is natural. I selected these images because they are a part of history. It was a part of who the ama were. That said, these photos were often intended for Western audiences. Soon after Japan opened, postcards of the exotic East began to be sent by visitors. Geisha, samurai, and ama numbered among the topics Westerners considered strange. Topless women who dived in cold waters. How strange! How erotic!

Never mind they dived nearly nude for safety. Clothing could snag on rocks. Although after the 1900s, many wore cotton gowns.

The exoticness of Japan was fetishized by the West since Japan modernized in the late 1800s. Today, Japanese women face continued fetishes by many Western men. These photos are not intended to cater to either fetish. Rather, I decided to use them to give a glimpsed of the women called ama while pointing out how these glimpses need to be understood. Today we sexualize far too much. The women you saw in this article felt the cold salt water on their skin. They knew hunger and joy. They were mothers and grandmothers. These photographs provide a small window in their lives, a window distorted by Western exoticism and by modern sexuality.

References

LeBlanc, P. (2015). UT professor studies group of traditional Japanese pearl divers. Austin American-Statesman.

McCurry, J. (2016) “Japan’s women of the sea hope G7 will boost their dying way of life; The ama divers of the Shima peninsula, who harvest shellfish from the seabed, see the nearby gathering of world leaders as a chance to promote their culture”. The Guardian (London).

Martinez, D. (2004) Identity and Ritual in A Japanese Diving Village: The Making and Becoming of Person and Place. University of Hawaii Press.

Tanaka, H. and others (2016) “Arterial Stiffness of lifelong Japanese female pearl divers.” Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310.

Photos are by Yoshiyuki Iwase unless otherwise noted.

Don’t know which Rabbit hole caused me to end up here, but I thoroughly enjoyed the read. Superb work!

Growing up in So Cal during the 70’s, I remember SeaWorld had a staged/Hollywood version of the Ama.

If anyone has a link to the NHK doc, please email me a link.

Thanks!

Here is one NHK documentary:

https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/ondemand/video/5006043/

It is an interesting rabbit hole. More interesting though is that in Edo Japan men in the Townsman and Peasant class could read and write and that the women helped with the family business. Also that fishermen were peasants and that the women in their family did the fishing that required diving.

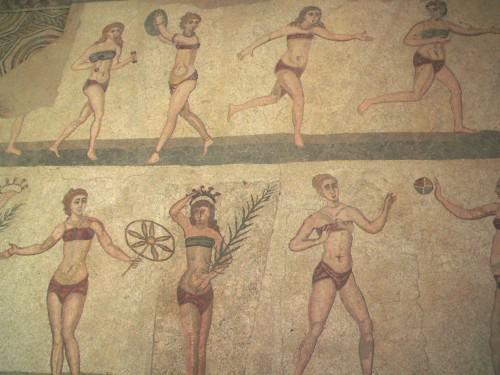

Historians often point out that the past wasn’t as patriarchal as once thought. In ancient Egypt, for example, especially during the Kushite period, women could own land and businesses and even be political leaders. In the Edo period, samurai women tended to have fewer rights than the farming classes but more access to education. Matriarchal structures appear to be rather common, especially in family units, even in patriarchal societies like Edo period Japan.

My mom had a two strings of pearls from shellfish retrieved by Ama, both acquired in the 60s. One string was of cultured pearls, from Mikimoto (near Ise), which was more oriented toward tourism. She mentioned that by that time the divers there wore white body-coverings so as not to offend Western visitors. The other string was from Uwajima in Shikoku, which she said was still a very traditional pearling area at that time.

Her take on photos of Ama was that except for those taken by Fosco Maraini, they were merely models posing for pictures usually sold to American servicemen and tourists. It would be interesting to know where Maraini documented the Ama he photographed.

I watched a documentary on NHK that spoke about how Ama tradition was ending in part because of climate change’s effects on the ocean.

The photos I could find in the library databases had a pin-up quality to them. It’s similar to how early Meiji photographs were aimed at the West for similar reasons. Thanks for pointing this out!

I don’t know much about shellfish farming; but while in Matsushima a few years back, it seemed that the large-scale oyster production in the bay didn’t require divers. Perhaps modern pearl production has simply rendered Ama an unnecessarily costly anachronism? I also wonder if it’s become a saturated market. Early on, Akoya pearls introduced a (relatively) affordable high-fashion item, creating a whole new market. But the only pearl I own (just one) is from Tahiti. Supply and demand?

I also surmise industrialization has more to do with the Ama’s decline than climate change, but the documentary was still interesting.

Just what I was able to discover regarding Fosco Maraini’s photos of the Ama, though you may already know this. In 1954, he took a film crew to document the daily lives of the “Ama” (海女), or “sea-women” of Hegura-jima, a small island in The Sea of Japan, north of Kanazawa. Maraini later included some of the collected still images in an Italian publication titled, “l’Isola delle Pescatrici” (The Isle of Fisherwoman). It looks like there was a Japanese edition as well, and it was apparently translated into English in 1962.

I think all of the photos in your article can be credited to Maraini. And looking through his collection, I believe he was also making a statement about the joy of life in a kind of unspoiled paradise. Much of his photography seems to show an appreciation for human beauty, especially in the smiles of his subjects.

I’d also be interested in knowing about the documentary you mentioned.

Thanks for the extra information! I did a poor job researching the photographs when I wrote this article. I found them on a library database that flagged them as Fair Use but didn’t have good bibliographic information. Libraries, like the Internet, sometimes lacks a chain of ownership. And, sometimes, I don’t do my due diligence, if I’m being honest.

I will hunt for the film. It sounds interesting!

One of the best I’ve read on the Ama. Thanks so much.

I’m glad you found it helpful.

Excellent article, thank you.