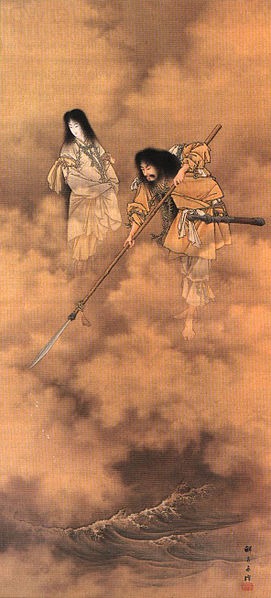

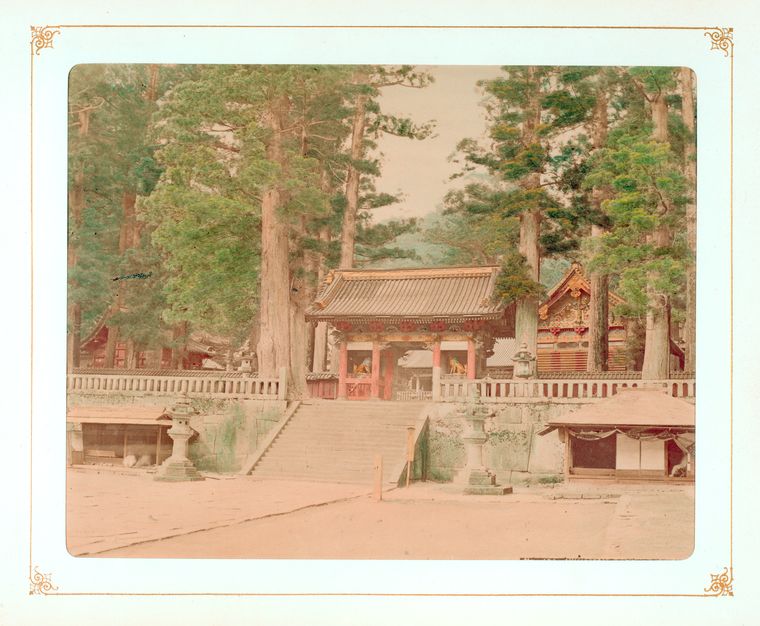

Myth is a word that gets thrown around a lot in media, and it is almost always used wrong. For many, myth is a synonym for lie. We say something is a myth in order to avoid the harsher word lie. Some of this comes from our Western Judaeo-Christian perspective. Creation stories from other religions, such as Japan’s Kojiki, are labeled as myths. That is, they are considered lies compared to Judaeo-Christian truth. This perspective is just as easily flipped. The story of Genesis is equally a myth from the perspective of Shinto and other religions.

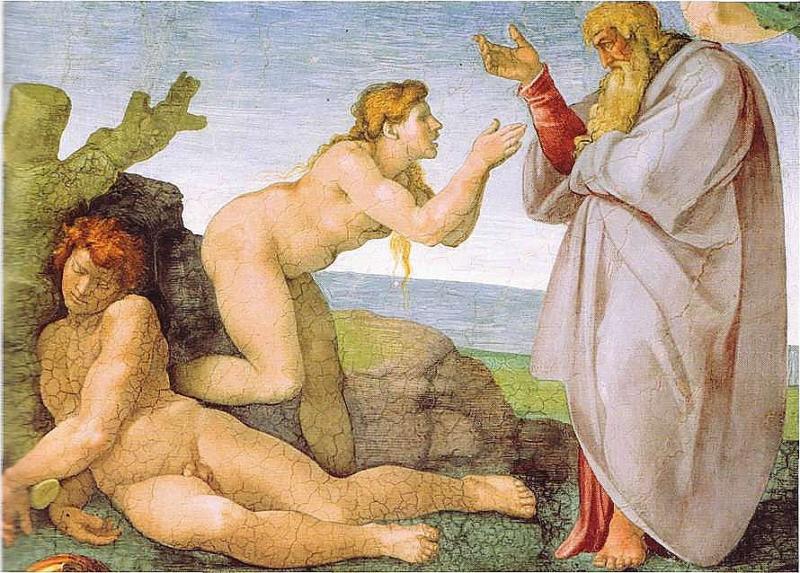

If you are a devoted Christian, your hackles are probably raising. The Story of Adam and Eve is a myth, just as the story of Amaterasu is a myth.

But the word myth is actually a good word.

Despite the misuse of the word, myth actually has more in common with the word truth. Part of the confusion comes from the postmodern view of morality and reality. Postmodernism and its close cousin Relativism do not believe in an objective truth, an objective set of morals and views of reality. Postmodernism believes some views are superior to others, but they are not universally true. Relativism believes all views are equally correct. On the other hand, myths come from a perspective that reality is governed by an objective, universal truth. Myths are stories that point to these truths.

Understanding the true meaning of the word myth is necessary to understand folklore and mythology. Myths are not concerned with facts. Our modern view equates facts with truth, but they are quite different. Facts are information without moral elements. They cannot be true or false. They can merely be correct or incorrect. We revise facts regularly as we learn more about how the physical world works. People used to believe the world was flat. This wasn’t a lie. It was merely the understanding people had based on the information available. The world is round isn’t a truth. It is a fact based on the information we have available.

Truth concerns itself with observing human nature and the nature of reality. Myths are stories that point toward truth. People may believe myths are factual, such as Genesis, but factuality isn’t as important as the truth myths reveal. People who view these as “merely” stories can still come away with Truth after reading them. Myth concerns itself with the human condition. They reveal whys behind human behavior and help explain why we view reality as we do. They explain suffering and why we suffer. Myths explain how behaviors create consequences. Trying to treat myths as literal history blinds us to the stories’ deeper messages.

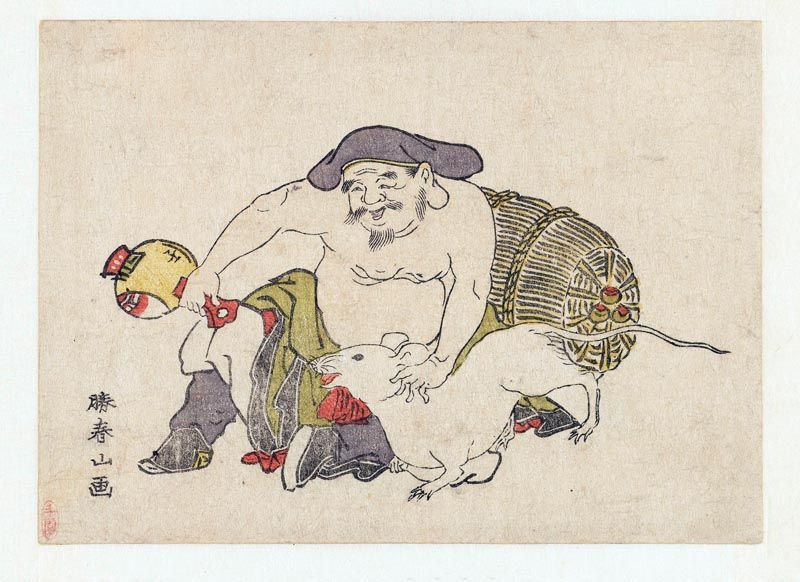

Myths and folklore and closely related. Mythology deals with provincial, top-down views of reality. Folklore deals with everyday, bottom-up experiences. Mythology starts with the elite and works down. Folklore starts with the peasant and works up. Both contain observations and lessons about reality. Sometimes folklore clashes with mythology. Folklore subverts the top-down narratives of the elite classes by poking fun at them or having simple farmers one-up some high-minded noble. Mythology seeks to establish a reason for the way society is structured, a justification for why elite classes can rule over the other social classes. The boundaries between the two types of stories are porous. Folklore can become myth.

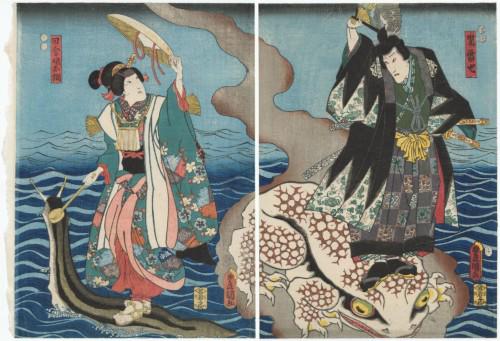

For example, the Japanese fox, Kitsune, began as a folk story that tweaked the noses of the elite classes of Japan. The fox was a create of farm fields and rural forests. Over time, the fox transformed into the avatar of Amaterasu, one of the most important Shinto goddesses. Eventually, the nine-tail fox avatars became the true form of the goddess. Amaterasu appears in the Kojiki as human, but after the folklore of kitsune became popular, she began to be portrayed as a type of fox. The fox avatar gave way to becoming the true form of the goddess.

Most myths began as folk stories. Each region had their own version, and each version contributed to the official myth as the stories merged. Kitsune was said to fertilize fields with her tail. Amaterasu gained this ability and became the Goddess of Rice. Kitsune stories were found throughout ancient and feudal Japan. Their popularity provided the groundwork for Amaterasu to become the most popular and most important god of Shinto. Yet, throughout this process the observations of these stories–what aspects of the human experience the fox symbolized–remained the same: the reality of raising food, the concerns about providing for your family, and other human concerns.

In our own time, the misunderstanding of the word myth fuels tension. The creation story in Genesis is seen as a ‘myth’ by those who do not believe it is a historical fact. Those who believe in the story’s factuality take offense to this. Both groups are missing the point. The story of Genesis concerns itself more with the nature of reality and human’s role within it than sketching a historical origin to creation. Genesis speaks about our responsibility as the gardener species. It points to how we can use our intellect selfishly in a way that damages the world, ourselves, and our loved ones (eating of the Tree of Knowledge) or in a way that benefits creation as God intended. It also speaks about the negative consequences of greed and impulsive action. Finally, it touches on the danger of words. Even a single shift in wording can change the meaning of a statement with long-lasting consequences. The story’s messages are far more important than its factual accuracy.

The debate about Genesis and other modern myths centers around our misunderstanding about facts and truth. Facts can lie. Truth can exist without fact. We know Aesop’s fables are fiction, but they contain truth.

The Lion, the Fox and the Ass entered into an agreement to assist each other in the chase. Having secured a large booty, the Lion on their return from the forest asked the Ass to allot his due portion to each of the three partners in the treaty. The Ass carefully divided the spoil into three equal shares and modestly requested the two others to make the first choice. The Lion, bursting out into a great rage, devoured the Ass. Then he requested the Fox to do him the favor to make a division. The Fox accumulated all that they had killed into one large heap and left to himself the smallest possible morsel. The Lion said, “Who has taught you, my very excellent fellow, the art of division? You are perfect to a fraction.” He replied, “I learned it from the Ass, by witnessing his fate.”

Be careful not to use the word myth when you mean to say lie or misconception. The creation story of Genesis is a myth. The Kojiki is a myth. Calling a misconception a myth slanders the truthfulness of these stories and other stories.