This story won our Japanese Fairy Tale Contest. She won the book Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide.

It is a strange event that I will tell you of, a moments when I was brushed by the shadow of something other. Do not shake your head. You know what I mean. I am sure of it; you, too, have once inadvertently hurried your step when you found yourself alone, in a silent place, in the murky light of an overcast sky, or you felt a strange shudder passing a bridge, or you saw something, in the corner of your eye, and then told yourself there was nothing, that there could not possibly have been anything… Am I right?

But they are rare, now. With every passing century, the twilight beings have receded further; I think they need a loneliness and silence lost to us. Who knows, now, what real darkness feels like, or utter silence? So, they no longer parade the streets or terrorize the traveller. But sometimes, I believe, they still lurk in the corners of our world, at borders and crossroads; when day turns to night, when summer’s heat and night’s cool intermingle in the streets during the short nights of summer, or when the sun blinds you over New Year’s snow. They may be without form, but they are waiting. Still waiting, on the threshold to elsewhere, to claim those foolish or ignorant enough to challenge them.

I was the happiest person on the planet the day they told me I won the scholarship for an exchange semester in Kyôto. Five months to explore the city, its countless temples and shrines – I would walk through the incense-infused half-light glimmering on the arms of a thousand thousand-armed gilded statues of Kannon, and sweat on the steep steps of Fushimi Inari’s mountain trek rimmed by Torii shrine gates, orange and red in the lush emerald forest, during the plum rain. And so I did. Every weekday was spent in language school, one day of every weekend I was round and about, exploring.

I was intrigued. Even more so, I was fascinated, for myth and fantasy have always been a subject close to my heart. So, although I had no idea what I hoped to find in the shop, I just dragged by bike up to the pavement, locked it to a cable pole and walked up to the entrance.

I looked in.

No, I can’t tell you what I saw, my memory is all but blank. Sometimes I think there was a man behind the counter, and another man he was talking to, standing with his back to me. But I don’t remember their faces, and I don’t remember hearing their voices either. All I can recall, so vividly it still gives me nausea when I remember it, is a wave of repulsion washing over me, an impulse so strong I was driven off like a leaf before the wind. I took a step backwards, turned, and almost broke into a run, my heart clutched by an invisible fist of fear. Unlocking my bike, I swung onto it, and tread the pedals like someone hunted by something invisible. And maybe I was. It did not occur to me to question my behaviour until I had reached the student accommodation where I lived. I guess I should have been glad they were content to scare me away… But that’s now how people are, right?

Kyôto has a long, rich and sometimes bloody history, and I wondered – had it been a summer night like this, near to a hundred and fifty years ago, when Kondô Isami took a fraction of the men of the Shinsengumi militia into what should be their most famous fight – the slaughter of the rônin conspirators at the Ikedaya Inn? They were only up against men, and they were trained warriors, while I was but a nosey girl; yet here I was, going to confront what might be anything from yakuza to yôkai. Gangsters or Monsters! What the hell am I doing, I thought, but at that point going back would have felt even more foolish.

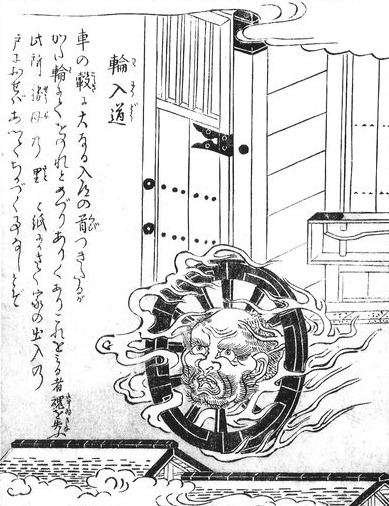

Unsurprisingly, Gion was still pretty lively. I hadn’t done much exploring in the ancient pleasure quarters yet, but I had visited the Yasaka Shrine only a few hours ago. As I passed it again, the doglike stone lions atop the stairs watching the main entrance seemed more significant to me, and less ridiculous. I retraced my steps northward on the Great Eastern Road and finally left my bike at a lamp post in a side street, a crossing or two before the weird shop. There was a great big sign telling me it was forbidden to leave bikes there, but I just hoped the Kyôto Police wouldn’t come around in the next half hour or so. Slowly, I walked on, my heart suddenly beating in my mouth as those cartwheels came back into my mind. I knew which yôkai that could be, from a book entry I had read back home. Wanyûdô, the head of a man, perhaps a monk, sitting in the middle of a burning wheel, who had murdered a woman’s child because she looked at the Night Parade of a Hundred Demons, instead of her baby. Probably there was a sutra to defend against him. Not that that would help me, now.

There were still a few pedestrians about, even though the shops were closed, and occasionally a car passed by. Yet I felt quite alone when the place I was looking for came in sight. Generally, the Japanese lit their cities as brightly as Christmas trees – but this particular house was sitting in what must have been the only comparably dark corner between here and the Pacific Ocean! That did not bode well. Warily, I approached, looking out for – what, foxfires? But no. It was just a dark, closed shop and quite prosaic on second glance, Kitarô figurine and all. I had probably only felt compelled to leave because the owner had glared at me, disapproving of a blue-eyed ginger Westerner sticking her head into his premises, I reasoned.

So I stood there for a minute or two, feeling both embarrassed and embarrassingly relieved. I had been so quick in running away before, I hadn’t even noticed what kind of shop this was! The sign, half-hidden by the junk around the upper level, was written in fading white paint, hard to read in the dark. I crossed the street, went up to the front to see better, and raised an eyebrow. The paint was not just faded; it was more like someone had tried to scrub it off, and given up halfway. But it definitely said ‘eye’ and ‘way’, and I remembered that the latter character was used in a couple of yôkai names, Wanyûdô among them. What was worse, up close the thing looked a lot like the signs used to indicate the names of temples. Where they selling leftovers from a dismantled holy site? When I went to the other side of the shop-front, squinting my eyes to peer through the gloom, I found some familiar-looking broken up carved boards up there, too. Not grey like this, but painted, brilliantly blue and green, offset with white against the orange building, such boards formed the eaves of many a temple. What might have happened to bring them here?

‘Hey, you.’

Every hair on my back stood on end. Someone had just addressed me in not-too-respectful Japanese, and there was a soft orange glow coming from behind me, a light which had not been there before and which was just strong enough to highlight a few items on the façade in front of me… and one grey, naked space. In front of the blue robot, a cartwheel was missing.

I did not turn. I did not think. I ran.

If I had been afraid in this afternoon, that was nothing compared to what I felt now. Judging by the flicker, the flames were already right behind me when I wrenched open my bike lock and jumped into the saddle, and I rushed down the street as fast as I possibly could. I did not even pause to put away my lock, instead holding it in my hand as I flew through the brightly lit streets, unaware of direction – until the steps with the stone lions appeared to my left.

This was the wrong way! I was going south, not north; away from the fragile promise of shelter in my home, instead of towards it. Panic had me in its claws, sharp and bitter. I didn’t bother to lock my bike anywhere, just left it on the side and ran up the steps, two at a time, no matter how steep they were. As I flew past bewildered late-hour shrine visitors, dark heads turned and someone said something in a disapproving tone, but I just kept going. I had no plan, no notion of where I was headed. I don’t think my conscious self had anything to do with it.

When I finally ran out of breath and clutched a stone torii for support, I found myself at a small Inari Shrine. The light of a single lamp shone on two white stone foxes guarding the entrance. Composing myself, I entered through the torii gate and walked up to them.

I have always likes these shrines. Foxes are the messengers of Inari, the god (or sometimes goddess) of rice – or alternatively, s/he likes to take their form her/himself. So, the shrines are guarded by stone foxes instead of the usual lions, making them easy to recognize. I was fond of foxes even before I came to Japan, and learning about the magic powers of the Japanese kitsune and how it grows an extra tail every hundred years of its long life, had quite intrigued me. I knew that foxes were often tricksters and shape-shifters and not exactly cuddly. But looking now upon the snarling jaws, the muscular bodies and strangely alive eyes of Inari’s foxes, I felt much safer than before. I passed the statues and walked up to the shrine proper. A small building of wood it was, of orange lacquered beams, filled in with white, their tips painted black, and the traditional bulky bronze roof was clean and shiny. Atop the miniature stairs of the shrine, in front of the gold-inlayed doors of the sanctuary housing the deity, stood a perfectly round polished mirror in a wooden stand. It reflected nothing but the bell on the rope which hung above the wooden box of offerings, but I wondered if I was looking upon a shintai – mirrors, like jewels and swords, often serve as such ‘god-bodies’ and become inhabited by the deity in rites and festivals. But would the priests expose it this way, instead of keeping it inside the sanctuary, behind the tiny golden doors?

When I pushed my hands into my pockets, I found a few coins. Small change from one of the rice cakes, mochi, I had become addicted to and bought far too often, no doubt. I bowed twice before the mirror and prayed, as good as I could. Inari-sama. I might have offended someone, but I am very sorry. Please help me. Protect me. I did not know the right words, and I was pretty sure you were supposed to address a deity in the most elaborate polite speech, but this way the extent of my Japanese proficiency, especially under duress. So I pulled the money out of my pocket, threw it into the offertory box and pulled the rope so that the bell rang merrily. Then I bowed again, took a deep breath and passed the stone foxes, leaving the way I came.

The thing was waiting for me as I stepped onto the walkway.

It was a grotesquely huge male head, twice the size of a human’s, mounted in the middle of a cartwheel; the spikes sprang from his cheeks, his temples, his chin, the crown of his head. Weirdly enough, I wasn’t even afraid now, despite the orange, strangely silent flames dancing all over the wheel, the spikes, and the grim face with its rolling eyes and enormous, yellow teeth.

‘You cannot run away!’, he said. His voice rumbled, like, well, like a cart on a bad road, and his speech was old-fashioned (or as I later assumed, regional dialect), but I recognized the word stem and the negation suffix.

‘It looks like it’, I replied after a pause. That seemed to surprise him. He stared rolling, circling me, drawing closer, and I stated back. ‘The barbarian girl speaks?!’ he thundered. Or maybe, ‘can speak?’ Evidently he had not expected me to be able to understand him, or even respond. Hope flickered up in my heart.

‘Yes.’ I lowered my head, then remembered I was in Japan and bowed, deeply, without rising. ‘I am sorry.’

He said something I didn’t quite understand, but he sounded more puzzled than angry. So I put everything on the line. I went down to my knees and cowered on the ground. ‘I am sorry I tried to enter the shop. I am sorry I came back to look at it. I am sorry I have… (I could not remember what ‘to offend’ meant) made you angry. Please forgive me.’ My heart was beating painfully now. Please, please, let this work… Please, make him go away.

‘Quite impressive’, a different voice said. Startled, I looked up, followed the gaze of the Wheel Monk, who looked surprised himself, and found a slender little fox sitting on top of Inari’s shrine gate. Now it descended, running down the post vertically for a bit, like a cat, before it jumped onto the footpath. Its red and white fur glistened in the light of the lamps in copper, gold and silver.

‘Do you still have a quarrel with this human, Wheel Monk?’ the fox asked. It spoke in the same, old-fashioned regional dialect as the Monk, but from now on I understood every word, although afterwards I have never been able to recall the words, only the meaning.

The Monk’s fiery brilliance seemed somewhat dimmed. ‘No’, he finally said. ‘I accept the apology.’

‘Then be gone’, the fox told him. ‘Your place is not here.’

So he rolled away, shimmering and fading as he went, until he was gone, like a mirage born of summer heat on the streets.

‘Thank you, thank you so much’, I said to the fox. It tilted its head and look up into my face.

‘You did well, all things considered’, it said. ‘But you called for help, and so I came. Be more careful from now on.’

‘Yes, I will. I promise.’ I put a hand on my heart.

‘Good. Remember.’ It beckoned me with its left forepaw, and as I crouched down, my braid slid over my shoulder. The fox came up to me, stood with its front legs on my thighs, the claws digging sharply into the thin jeans fabric, and sniffed. Its breath tickled my neck, smelling of sweet tofu. ‘No, you’re human’, it said. ‘With that hair, I thought you might be a granddaughter of ours.’ It sat down on its hind legs, again reminding me of a cat, and held its left paw before me. When I stretched out my hand, it put the paw in my palm, let it rest there for a moment, and then pulled back. Looking at my hand, I found a tiny bag made of silk brocade, tied with an elaborate symmetrical knot – a mamori or protective charm. ‘Thank you!’ I called out again – but the footpath was empty now, and only silent stone statues guarded Inari’s shrine.

Hugging the charm to my breast, I bowed again to the shrine a couple of times, and then I stumbled back, out of the shrine precinct, down the steep steps to the Great Eastern Road. Miraculously, my bike was still where I had left it.

I cycled home and went straight to bed. The next morning, I wondered if I had dreamt the whole thing. You may choose to believe that. But sometimes, when I show a certain green mamori to friends, they all say the same thing about the embroidered image.

‘A fox chasing a wheel? Curious!’