In a certain Japanese village there grew a great willow-tree. For many generations the people loved it. In the summer it was a resting-place, a place where the villagers might meet after the work and heat of the day were over, and there talk till the moonlight streamed through the branches. In winter it was like a great half-opened umbrella covered with sparkling snow.

In a certain Japanese village there grew a great willow-tree. For many generations the people loved it. In the summer it was a resting-place, a place where the villagers might meet after the work and heat of the day were over, and there talk till the moonlight streamed through the branches. In winter it was like a great half-opened umbrella covered with sparkling snow.

Heitaro, a young farmer, lived quite near this tree, and he, more than any of his companions, had entered into a deep communion with the imposing willow. It was almost the first object he saw upon waking, and upon his return from work in the fields he looked out eagerly for its familiar form. Sometimes he would burn a joss-stick beneath its branches and kneel down and pray.

One day an old man of the village came to Heitaro and explained to him that the villagers were anxious to build a bridge over the river, and that they particularly wanted the great willow-tree for timber.

“For timber?” said Heitaro, hiding his face in his hands. “My dear willow-tree for a bridge, one to bear the incessant patter of feet? Never, never, old man!”

When Heitaro had somewhat recovered himself, he offered to give the old man some of his own trees, if he and the villagers would accept them for timber and spare the ancient willow.

The old man readily accepted this offer, and the willow-tree continued to stand in the village as it had stood for so many years.

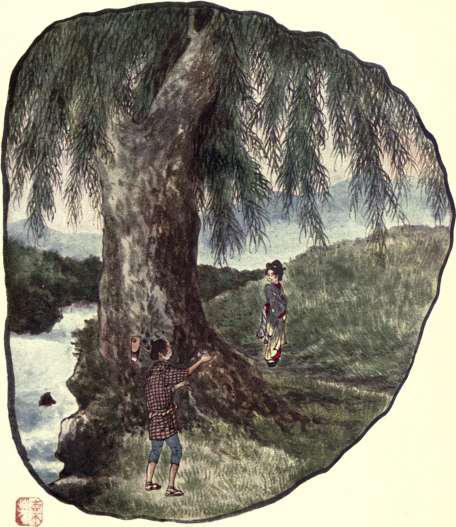

One night while Heitaro sat under the great willow he suddenly saw a beautiful woman standing close beside him, looking at him shyly, as if wanting to speak.

“Honourable lady,” said he, “I will go home. I see you wait for some one. Heitaro is not without kindness towards those who love.”

“He will not come now,” said the woman, smiling.

“Can he have grown cold? Oh, how terrible when a mock love comes and leaves ashes and a grave behind!”

“He has not grown cold, dear lord.”

“And yet he does not come! What strange mystery is this?”

“He has come! His heart has been always here, here under this willow-tree.” And with a radiant smile the woman disappeared.

Night after night they met under the old willow-tree. The woman’s shyness had entirely disappeared, and it seemed that she could not hear too much from Heitaro’s lips in praise of the willow under which they sat.

One night he said to her: “Little one, will you be my wife—you who seem to come from the very tree itself?”

“Yes,” said the woman. “Call me Higo (“Willow”) and ask no questions, for love of me. I have no father or mother, and some day you will understand.”

“Yes,” said the woman. “Call me Higo (“Willow”) and ask no questions, for love of me. I have no father or mother, and some day you will understand.”

Heitaro and Higo were married, and in due time they were blessed with a child, whom they called Chiyodō. Simple was their dwelling, but those it contained were the happiest people in all Japan.

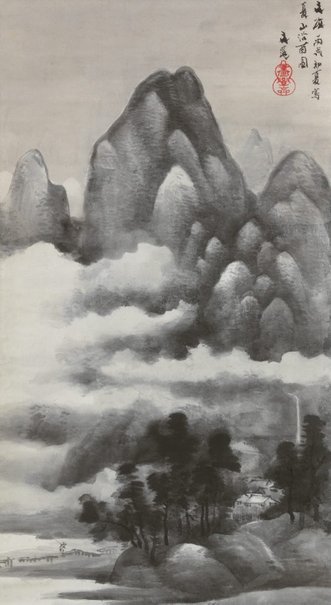

While this happy couple went about their respective duties great news came to the village. The villagers were full of it, and it was not long before it reached Heitaro’s ears. The ex-Emperor Toba wished to build a temple to Kwannon in Kyōto, and those in authority sent far and wide for timber. The villagers said that they must contribute towards building the sacred edifice by presenting their great willow-tree. All Heitaro’s argument and persuasion and promise of other trees were ineffectual, for neither he nor any one else could give as large and handsome a tree as the great willow.

Heitaro went home and told his wife. “Oh, wife,” said he, “they are about to cut down our dear willow-tree! Before I married you I could not have borne it. Having you, little one, perhaps I shall get over it some day.”

That night Heitaro was aroused by hearing a piercing cry. “Heitaro,” said his wife, “it grows dark! The room is full of whispers. Are you there, Heitaro? Hark! They are cutting down the willow-tree. Look how its shadow trembles in the moonlight. I am the soul of the willow-tree! The villagers are killing me. Oh, how they cut and tear me to pieces! Dear Heitaro, the pain, the pain! Put your hands here, and here. Surely the blows cannot fall now?”

“My Willow Wife! My Willow Wife!” sobbed Heitaro.

“Husband,” said Higo, very faintly, pressing her wet, agonized face close to his, “I am going now. Such a love as ours cannot be cut down, however fierce the blows. I shall wait for you and Chiyodo—— My hair is falling through the sky! My body is breaking!”

There was a loud crash outside. The great willow-tree lay green and disheveled upon the ground. Heitaro looked round for her he loved more than anything else in the world. Willow Wife had gone!

—

I included this and other tree stories in my book, Under the Cherry Blossoms: An Introduction to Japanese Tree Folklore.

References

Davis, F Hadland (1912). Myths and Legends of Japan. George G Harrap and Company, London.