There lived in the village a young farmer named Heitaro, a great favorite, who had lived near the old tree all his days, as his forefathers had done ; and he was greatly against cutting it down.

Such a tree should be respected, thought he. Had it not braved the storms of hundreds of years ? In the heat of summer what pleasure it afforded the children ! Did it not give to the weary shelter, and to the love-smitten a sense of romance ? All these thoughts Heitaro impressed upon the villagers. Sooner than approve your cutting it down/ he said, “I will give you as many of my own trees as you require to build the bridge. You must leave this dear old willow alone for ever/

The villagers readily agreed. They also had a secret veneration for the old tree.

Heitaro was delighted, and readily found wood with which to build the bridge.

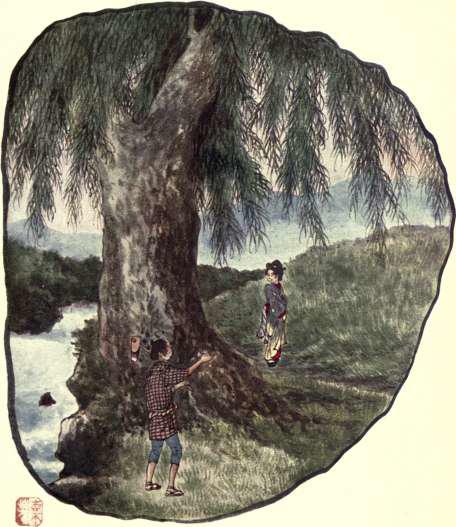

Some days later Heitaro, returning from his work, found standing by the willow a beautiful girl.

Instinctively he bowed to her. She returned the bow. They spoke together of the tree, its age and beauty. They seemed, in fact, to be drawn towards each other by a common sympathy. Heitaro was sorry when she said that she must be going, and bade him good-day. That evening his mind was far from being fixed on the ordinary things of life. “Who was the lady under the willow tree ? How I wish I could see her again!’“thought he. There was no sleep for Heitaro that night. He had caught the fever of love.

Next day he was at his work early ; and he remained at it all day, working doubly hard, so as to try and forget the lady of the willow tree ; but on his way home in the evening, behold, there was the lady again ! This time she came forward to greet him in the most friendly way.

“Welcome, good friend !”she said. “Come and rest under the branches of the willow you love so well, for you must be tired.”

Heitaro readily accepted this invitation, and not only did he rest, but also he declared his love.

Day by day after this the mysterious girl (whom no others had seen) used to meet Heitaro, and at last she promised to marry him if he asked no questions as to her parents or friends. “I have none,” she said. “I can only promise to be a good and faithful wife, and tell you that I love you with all my heart and soul. Call me, then, ” Higo,” J and I will be your wife.”

Next day Heitaro took Higo to his house, and they were married. A son was born to them in a little less than a year, and became their absorbing joy. There was not a moment of their spare time in which either Heitaro or his wife was not playing with the child, whom they called Chiyodo. It is doubtful if a more happy home could have been found in all Japan than the house of Heitaro, with his good wife Higo and their beautiful child.

Alas, where in this world has complete happiness ever been known to last ? Even did the gods permit this, the laws of man would not.

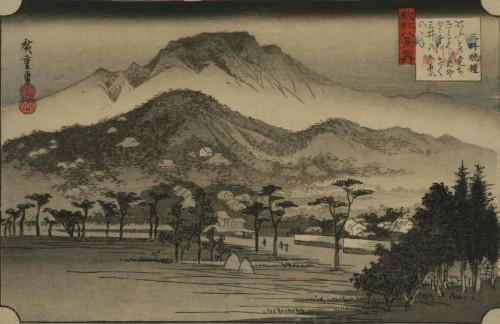

When Chiyodo had reached the age of five years— the most beautiful boy in the neighbourhood—the ex-Emperor Toba decided to build in Kyoto an immense temple to Kwannon. He would contribute 1001 images of the Goddess of Mercy.

The ex-Emperor Toba’s wish having become known, orders were given by the authorities to collect timber for the building of the vast temple ; and so it came to pass that the days of the big willow tree were numbered, for it would be wanted, with many others, to form the roof.

Heitaro tried to save the tree again by offering every other he had on his land for nothing, but that was in vain. Even the villagers became anxious to see their willow tree built into the temple. It would bring them good luck, they thought, and in any case be a handsome gift of theirs towards the great temple.

The fatal time arrived. One night, when Heitaro and his wife and child had retired to rest and were sleeping, Heitaro was awakened by the sound of axes chopping. To his astonishment, he found his beloved wife sitting up in her bed, gazing earnestly at him, while tears rolled down her cheeks and she was sobbing bitterly.

“My dearest husband,”she said with choking voice, “ pray listen to what I tell you now, and do not doubt me. This is, unhappily, not a dream. When we married I begged you not to ask me my history, and you have never done so, but I said I would tell you some day if there should be a real occasion to do so. Unhappily, that occasion has now arrived, my dear husband. I am no less a thing than the spirit of the willow tree you loved, and so generously saved six years ago. It was to repay you for this great kindness that I appeared to you in human form under the tree, hoping that I could live with you and make you happy for your whole life. Alas, it cannot be! They are cutting down the willow. How I feel every stroke of their axes! I must return to die, for I am part of it. My heart breaks to think also of leaving my darling child Chiyodo and of his great sorrow when he knows that his mother is no longer in the world. Comfort him, dearest husband! He is old enough and strong enough to be with you now without a mother and yet not suffer. I wish you both long lives of prosperity. Farewell, my dearest ! I must be off to the willow, for I hear them striking with their axes harder and harder, and it weakens me each blow they give.

Heitaro awoke his child just as Higo disappeared, wondering to himself if it were not a dream. No : it was no dream. Chiyodo, awaking, stretched his arms in the direction his mother had gone, crying bitterly and imploring her to come back.

“My darling child,”said Heitaro, “she has gone. She cannot come back. Come, let us dress, and go and see her funeral. Your mother was the spirit of the Great Willow.”

A little later, at the break of day, Heitaro took Chiyodo by the hand and led him to the tree. On reaching it they found it down, and already lopped of its branches. The feelings of Heitaro may be well imagined.

Strange ! In spite of united efforts, the men were unable to move the stem a single inch towards the river, in which it was to be floated to Kyoto.

On seeing this, Heitaro addressed the men.

“My friends,” said he, “the dead trunk of the tree which you are trying to move contains the spirit of my wife. Perhaps, if you will allow my little son Chiyodo to help you, it will be more easy for you ; and he would like to help in showing his last respects to his mother.’

The woodcutters were fully agreeable, and, much to their astonishment, as Chiyodo came to the back end of the log and pushed it with his little hand, the timber glided easily towards the river, his father singing the while an “Uta.” There is a well-known song or ballad in the “Uta”style said to have sprung from this event; it is sung to the present day by men drawing heavy weights or doing hard labor:

Is it not sad to see the little fellow,

Who sprang from the dew of the Kumano Willow,

And is thus far budding well ?

Heave ho, heave ho, pull hard, my lads.

The wagon could not be drawn when it came to the front of Heitaro’s house, so his little five-year-old boy Chiyodo was obliged to help, and they sang :—

Is it not sad to see the little fellow,

Who sprang from the dew of the Kumano Willow,

And is thus far budding well ?

Heave ho, heave ho, pull hard, my lads.

There are many different versions of this story. This is one of the most detailed. Japanese folklore rarely end “happily ever after.” The stories capture the reality of intertwined happiness and sorrow. Even the closest lovers must part for a time when one of them dies. However, these stories aren’t pessimistic. Rather, they seek to teach appreciation. We appreciate what we have more when we know it must end.

References

Smith, Richard Gordon (1918) Ancient Tales and Folklore of Japan.