Let’s take a break from monsters and look at how insects are said to have lived in yet another of William Griffis’s collected tales from Japan.

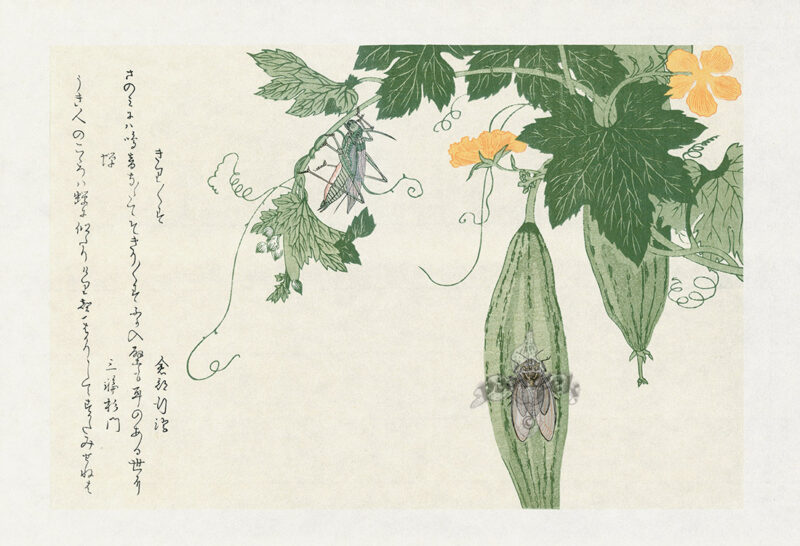

Lovely and bright in the month of May, at the time of rice-planting, was the day on which the daimio, Lord Long-legs, was informed by his chamberlain, Hop-hop, that on the morrow his lordship’s retinue would be in readiness to accompany their worshipful Lord Long-legs on his journey. This Lord Long-legs was a daimio who ruled over four acres of rice-field in Echizen, whose revenue was ten thousand rice-stalks. His retainers, who were all grasshoppers, numbered over six thousand, while his court consisted only of nobles, such as Mantis, Beetle, and Pinching-bug. The maids of honor who waited on his queen Katydid, were lady-bugs, butterflies, and goldsmiths, and his messengers were fire-flies and dragon-flies. Once in a while a beetle was sent on an errand; but these stupid fellows had such a habit of running plump into things, and bumping their heads so badly that they always forgot what they were sent for. Besides these, he had a great many servants in the kitchen—such as grubs, spiders, toads, etc. The entire population of his dominion, including the common folks, numbered several millions, and ranked all the way from horse-flies down to ants, mosquitoes, and ticks.

Many of his subjects were very industrious and produced fine fabrics, which, however, were seized and made use of by great monsters, called men. Thus the gray worms kept spinning-wheels in their heads. They had a fashion of eating mulberry leaves, and changing them into fine threads, called silk. The wasps made paper, and the bees distilled honey. There was another insect which spread white wax on the trees. These were all retainers or friendly vassals of Lord Long-legs.

Now it was Lord Long-legs’ duty once a year to go up to Yedo to pay his respects to the great Tycoon and to spend several weeks in the Eastern metropolis. I shall not take the time nor tax the patience of my readers in telling about all the bustle and preparation that went on in the yashiki (mansion) of Lord Long-legs for a whole week previous to starting. Suffice it to say that clothes were washed and starched, and dried on a board, to keep them from shrinking; trunks and baskets were packed; banners and umbrellas were put in order; the lacquer on the brass ornaments; shields and swords and spears were all polished; and every little item was personally examined by the daimio’s chief inspector. This functionary was a black-and-white-legged mosquito, who, on account of his long nose, could pry into a thing further and see it easier than any other of his lordship’s officers; and, if anything went wrong, he could make more noise over it than any one else. As for the retainers, down to the very last lackey and coolie, each one tried to outshine the other in cleanliness and spruce dress.

The Bumble-bee brushed off the pollen from his legs; and the humbler Honey-bee, after allowing his children to suck his paws, to get the honey sticking to them, spruced up and listened attentively to the orders read to him by the train-leader, Sir Locust, who prided himself on being seventeen years old, and looked on all the others as children. He read from a piece of wasp-nest paper: “No leaving the line to suck flowers, except at halting-time.” The Blue-tailed Fly washed his hands and face over and over again. The lady-bugs wept many tears, because they could not go with the company; the crickets chirped rather gloomily, because none with short limbs could go on the journey; while Daddy Long-legs almost turned a somersault for joy when told he might carry a bundle in the train. All being in readiness, the procession was to start at six o’clock in the morning. The exact minute was to be announced by the time-keeper of the mansion, Flea san, whose house was on the back of Neko, a great black cat, who lived in the porter’s lodge of the castle, near by. Flea san was to notice the opening or slits in the monster’s moony-green eyes, which when closed to a certain width would indicate six o’clock. Then with a few jumps she was to announce it to a mosquito friend of hers, who would fly with the news to the gate-keeper of the yashiki, one Whirligig by name.

So, punctually to the hour, the great double gate swung wide open, and the procession passed out and marched on over the hill. All the servants of Lord Long-legs were out, to see the grand sight. They were down on their knees, saying: “O shidzukani,” (please go slowly). When their master’s palanquin passed, they bowed their heads to the dust, as was proper. The ladies, who were left behind, cried bitterly, and soaked their paper handkerchiefs with tears, especially one fair brown creature, who was next of kin to Lord Long-legs, being an ant on his mother’s side.

The procession was closed by six old daddies (spiders), marching two by two, who were a little stupid and groggy, having had a late supper, and a jolly feast the night before. When the great gate slammed shut, one of them caught the end of his foot in it, and was lamed for the rest of the journey. This old Daddy Long-legs, hobbling along, with a bundle on his back, was the only funny thing in the procession, and made much talk among bystanders on the road.

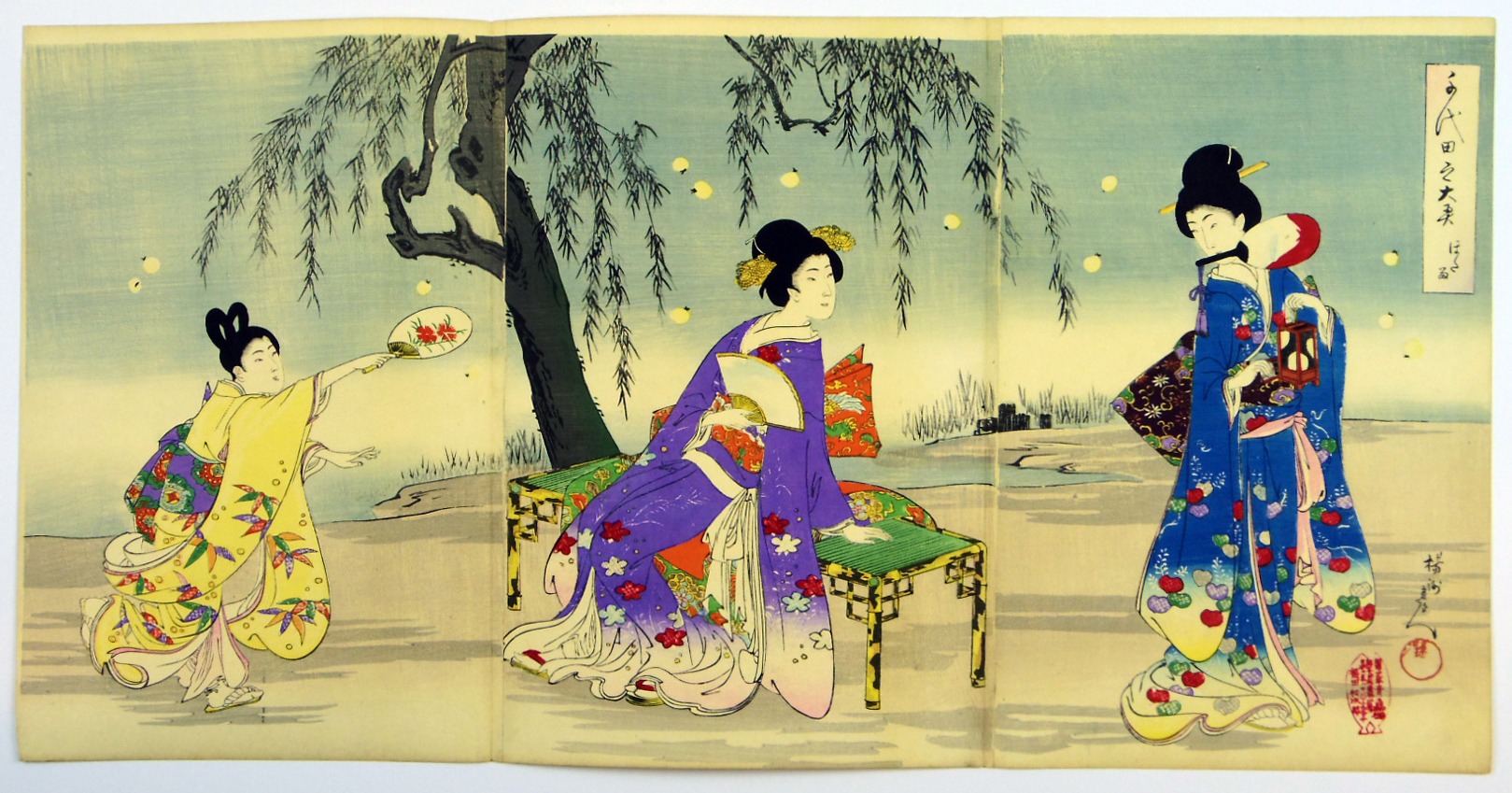

This is the order and the way they looked. First there went out, far ahead, a plump, tall Mantis, with a great long baton of grass, which he swung to and fro before him, from right to left, (like a drum-major), crying out: “Shitaniro, down on your knees! Get down with you!” Whereat all the ants, bugs and lizards at once bent their forelegs, and the toads, which were already squatting, bobbed their noses in the dust. Even the mud-turtles poked their heads out of the water to see what was going on. All the worms and grubs who lived up in trees or tall bushes had to come down to the ground. It was forbidden to any insect to remain on a high stalk of grass, lest he might look down on His Highness. Even the Inch-worm had to wind himself up and stop measuring his length, while the line was passing. And in case of grubs or moths in the nest or cocoon, too young to crawl out, the law compelled their parents to cover them over with a leaf. It would be an insult to Lord Long-legs to look down on him. Next followed two lantern-bearers, holding glow-worms for lanterns in their fore-paws. These were wrapped in cases made of leaves, which they took off at night. Behind were six fire-flies, well supplied with self-acting lamps, which they kept hidden somewhere under their wings. Next marched four abreast the band of little weevils, carrying the umbrellas of state, which were morning-glories—some open, some shut. Behind them strutted four green grasshoppers, who were spear-bearers, carrying pink blossoms. Just before the palanquin were two tall dandies, high lords themselves and of gigantic stature and imposing bellies, who, with arms akimbo and feelers far up in the air, bore aloft high over all the insignia of their Lord Long-legs. All these fellows strutted along on their hind legs, their backs as stiff as a hemp stalk, their noses pointing to the stars, and their legs striding like stilts. The priest in his robes, a praying beetle, who was chaplain, walked on solemnly.

Meanwhile a great crowd of spectators lined the path; but all were on their knees. Frogs and toads blinked out of the sides of their heads. The pretty red lizards glided out, to see the splendid show; worms stopped crawling; and all kinds of bugs ceased climbing, and came down from the grass and flower-stalks, to bow humbly before the train of Lord Long-legs. Bug mothers hastened, with their bug babies on their backs, down to the road, and, squatting down, taught their little nits to put their fore-paws politely together and bow down on their front knees. No one dared to speak out loud; but the mole-cricket, nudging his fellow under the wing, said: “Just look at that green Mantis! He looks as though ‘he would rush out with a battle-ax on his shoulder to meet a chariot.’ See how he ogles his fellow!”

“Yes; and just behold that bandy-legged hopper, will you? I could walk better than that myself,” said the other.

“‘Sh!” said the mole-cricket. “Here comes the palanquin.”

Everybody now cast a squint up under their eyebrows, and watched the palanquin go by. It was made of delicately-woven striped grass, bound with bamboo threads, lacquered, and finished with curtains of gauze, made of dragon-fly wings, through which Lord Long-legs could peep. It was borne on the shoulders of four stalwart hoppers, who, carrying rest-poles of grass, trudged along, with much sweat and fuss and wiping of their foreheads, stopping occasionally to change shoulders. At their side walked a body-guard of eight hoppers, armed with pistils, and having side-arms of sword-grass. They were also provided with poison-shoots, in case of trouble. Other bearers followed, keeping step and carrying the regalia, consisting of chrysanthemum stalks and blossoms. Then followed, in double rank, a long string of wasps, who were for show and nothing more. Between them, inside, carefully saddled, bridled, and in full housings, was a horse-fly, led by a snail, to keep the restive animal from going at a too rapid pace.

Three big, gawky helmet-headed beetles next followed, bearing rice-sprouts, with full heads of rice.

“Oh! oh! look there!” cried a little grub at the side of the road. “See the little grasshopper riding on his father’s back!”

“Hai,” said Mother Butterfly, putting one paw on her baby’s neck, for fear of being arrested for making a noise.

It was so. The little ‘hopper, tired of long walking, had climbed on his father’s back for a ride, holding on by the feelers and seeing everything.

Finally, toward the end of the procession, was a great crowd of common ‘hoppers, beetles, and bugs of all sorts, carrying the presents to be given in Yedo, and the clothing, food and utensils for the use of Lord Long-legs on the journey; for the hotels were sometimes very poor on the Tokaido high road, and the daimio liked his comforts. Besides, it was necessary for Lord Long-legs to travel with proper dignity, as became a daimio. His messengers always went before and engaged lodging-places, as the fleas, spiders and mosquitoes from other localities, who traveled up and down the great high road, sometimes occupied the places first. The procession wound up by the rear-guard of Daddy Long-legs, who prevented any insult or disrespect from the rabble. After the line had passed, insects could cross the road, traffic and travel were resumed, and the road was cleared, while the procession faded from view in the distance.

References

Griffis, William Elliot (1887). Japanese Fairy World. London: Trubner & Co. Ludgate Hill.