He dreamed he was far away in China, walking along the banks of the great Yellow River. Everything was very strange. The people talked an entirely different language from his own; had on different clothes; and, instead of the nice shaven head and top-knot of the Japanese, every one wore a long pigtail of hair, that dangled at his heels. Even the boats were of a strange form, and on the fishing smacks perched on projecting rails, sat rows of cormorants, each with a ring around his neck. Every few minutes one of them would dive under the water, and after a while come struggling up with a fish in its mouth, so big that the fishermen had to help the bird into the boat. The game was then flung into a basket, and the cormorant was treated to a slice of raw fish, by way of encouragement and to keep the bird from the bad habit of eating the live fish whole. This the ravenous bird would sometimes try to do, even though the ring was put around his neck for the express purpose of preventing him from gulping down a whole fish at once.

It was springtime, and the buds were just bursting into flower. The river was full of fish, especially of carp, ascending to the great rapids or cascades. Here the current ran at a prodigious rate of swiftness, and the waters rippled and boiled and roared with frightful noise. Yet, strange to say, many of the fish were swimming up the stream as if their lives depended on it. They leaped and floundered about; but every one seemed to be tossed back and left exhausted in the river, where they panted and gasped for breath in the eddies at the side. Some were so bruised against the rocks that, after a few spasms, they floated white and stiff, belly up, on the water, dead, and were swept down the stream. Still the shoal leaped and strained every fin, until their scales flashed in the sun like a host of armored warriors in battle. Gojiro, enjoying it as if it were a real conflict of wave and fishes, clapped his hands with delight.

Then Gojiro inquired, by means of writing, of an old white-bearded sage standing by and looking on: “What is the name of this part of the river?”

“We call it Lung Men,” said the sage.

“Will you please write the characters for it,” said Gojiro, producing his ink-case and brush-pen, with a roll of soft mulberry paper.

The sage wrote the two Chinese characters, meaning “The Gate of the Dragons,” or “Dragons’ Gate,” and turned away to watch a carp that seemed almost up into smooth water.

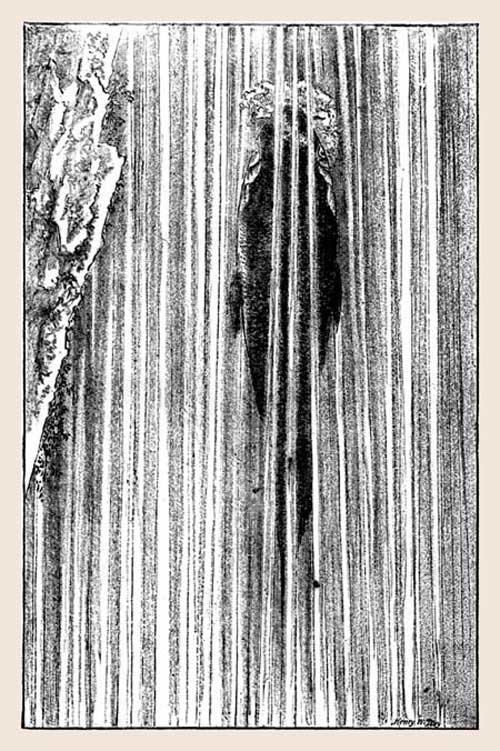

“Oh! I see,” said Gojiro to himself. “That’s pronounced Riu Mon in Japanese. I’ll go further on and see. There must be some meaning in this fish-climbing.” He went forward a few rods, to where the banks trended upward into high bluffs, crowned by towering firs, through the top branches of which fleecy white clouds sailed slowly along, so near the sky did the tree-tops seem. Down under the cliffs the river ran perfectly smooth, almost like a mirror, and broadened out to the opposite shore. Far back, along the current, he could still see the rapids shelving down. It was crowded at the bottom with leaping fish, whose numbers gradually thinned out toward the center; while near the top, close to the edge of level water, one solitary fish, of powerful fin and tail, breasted the steep stream. Now forward a leap, then a slide backward, sometimes further to the rear than the next leap made up for, then steady progress, then a slip, but every moment nearer, until, clearing foam and ripple and spray at one bound, it passed the edge and swam happily in smooth water.

It was inside the Dragon Gate.

Now came the wonderful change. One of the fleecy white clouds suddenly left the host in the deep blue above, dipped down from the sky, and swirling round and round as if it were a water spout, scratched and frayed the edge of the water like a fisher’s troll. The carp saw and darted toward it. In a moment the fish was transformed into a white dragon, and, rising into the cloud, floated off toward Heaven. A streak or two of red fire, a gleam of terrible eyes, and the flash of white scales was all that Gojiro saw. Then he awoke.

“How strange that a poor little carp, a common fish that lives in the river, should become a great white dragon, and soar up into the sky, to live there,” thought Gojiro, the next day, as he told his mother of his dream.

“Yes,” said she; “and what a lesson for you. See how the carp persevered, leaping over all difficulties, never giving up till it became a dragon. I hope my son will mount over all obstacles, and rise to honor and to high office under the government.”

“Oh! oh! now I see!” said Gojiro. “That is what my teacher means when he says the students in Tokio have a saying, ‘I’m a fish today, but I hope to be a dragon tomorrow,’ when they go to attend examination; and that’s what Papa meant when he said: ‘That fish’s son, Kofuku, has become a white dragon, while I am yet only a carp.'”

So on the third day of the third month, at the Feast of Flags, Gojiro hoisted the nobori. It was a great fish, made of paper, fifteen feet long and hollow like a bag. It was yellow, with black scales and streaks of gold, and red gills and mouth, in which two strong strings were fastened. It was hoisted up by a rope to the top of a high bamboo pole on the roof of the house. There the breeze caught it, swelled it out round and full of air. The wind made the fins work, and the tail flap, and the head tug, until it looked just like a carp trying to swim the rapids of the Yellow River—the symbol of ambition and perseverance.

This story explains the folklore origin of the nobori banner flown as a traditional wish for health and prosperity. May 5th stands as a holiday called “Children’s Day” since World War II. Koi-nobori fly for each member of the family. The festival traces back to the 18th and 19th century where boys staged battles using iris leaves as swords. Tradition calls the holiday Shobu no Sekku, festival of the irises, for this reason. The festival sought to recreate the battles between the 12th century families Genji and Heike. The festival acts as a prayer for young boys to grow up strong and courageous.

So why the carp? The carp, or koi, stands as a symbol of courage and strength because it can leap up waterfalls as we’ve seen in Gojiro’s story. Folklore captures the reasons for festivals in fantastic stories such as this. In this case, the wish for children to grow strong enough to become successful: dragons.

References

Griffis, William Elliot (1887) Japanese Fairy World: Stories from the Wonder-lore of Japan. London: Trubner and Company.