Kiyohimé was written down around 1887 and contains dated language and spellings. This period brought many stories from Japan to the West. I left the language unchanged; I find the language charming. A bonze is another name for a Japanese or Chinese monk. A bonzerie is a monastery.

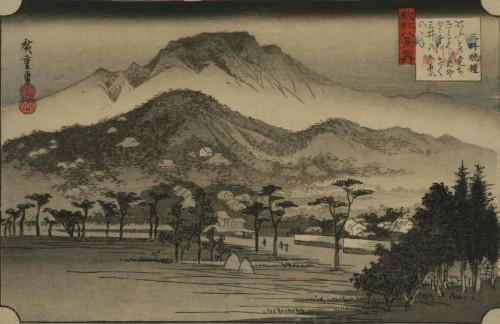

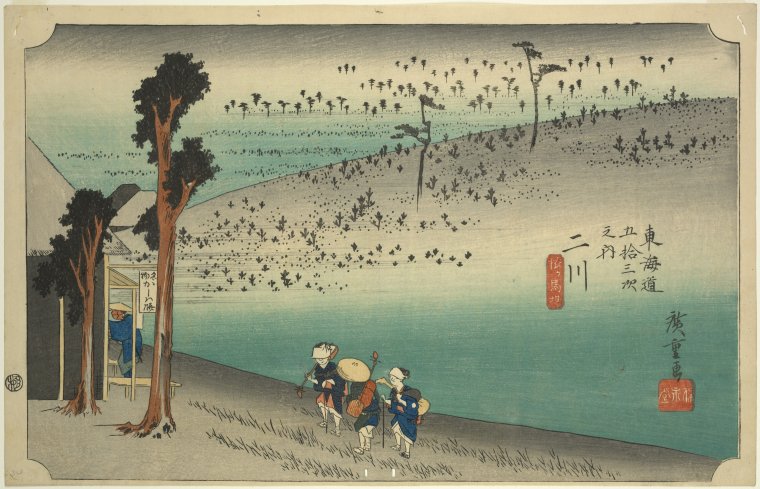

Quiet and shady was the spot in the midst of one of the loveliest valley landscapes in the empire, near the banks of the Hidaka river, where stood the tea-house kept by one Kojima. It was surrounded on all sides by glorious mountains, ever robed with deep forests, silver-threaded with flashing water-falls, to which the lovers of nature paid many a visit, and in which poets were inspired to write stanzas in praise of the white foam and the twinkling streamlets. Here the bonzes loved to muse and meditate, and anon merry picnic parties spread their mats, looped their canvas screens, and feasted out of nests of lacquered boxes, drinking the amber saké from cups no larger nor thicker than an egg-shell, while the sound of guitar and drum kept time to dance and song.

The garden of the tea-house was as lovely a piece of art as the florist’s cunning could produce. Those who emerged from the deep woods of the lofty hill called the Dragon’s Claw, could see in the tea-house garden a living copy of the landscape before them. There were mimic mountains, (ten feet high), and miniature hills veined by a tiny, path with dwarfed pine groves, and tiny bamboo clumps, and a patch of grass for meadow, and a valley just like the great gully of the mountains, only a thousand times smaller, and but twenty feet long. So perfect was the imitation that even the miniature irrigated rice-fields, each no larger than a checker-board, were in full sprout. To make this little gem of nature in art complete, there fell from over a rock at one end a lovely little waterfall two feet high, which after an angry splash over the stones, rolled on over an absurdly small beech, all white-sanded and pebbled, threading its silver way beyond, until lost in fringes of lilies and aquatic plants. In one broad space imitating a lake, was a lotus pond, lined with iris, in which the fins of gold fish and silver carp flashed in the sunbeams. Here and there the nose of a tortoise protruded, while on a rugged rock sat an old grandfather surveying the scene with one or two of his grand-children asleep on his shell and sunning themselves.

The fame of the tea-house, its excellent fare, and special delicacy of its mountain trout, sugar-jelly and well-flavored rice-cakes, drew hundreds of visitors, especially poetry-parties, and lovers of grand scenery.

Just across the river, which was visible from the verandah of the tea-house, stood the lofty firs that surrounded the temple of the Tendai Buddhists. Hard by was the pagoda, which painted red peeped between the trees. A long row of paper-windowed and tile-roofed dwellings to the right made up the monastery, in which a snowy eye-browed but rosy-faced old abbot and some twenty bonzes dwelt, all shaven-faced and shaven-pated, in crape robes and straw sandals, their only food being water and vegetables.

Not the least noticeable of the array of stone lanterns, and bronze images with aureoles round their heads, and incense burners and holy water tanks, and dragon spouts, was the belfry, which stood on a stone platform. Under its roof hung the massive bronze bell ten feet high, which, when struck with a suspended log like a trip-hammer, boomed solemnly over the valley and flooded three leagues of space with the melody which died away as sweetly as an infant falling in slumber. This mighty bell was six inches thick and weighed several tons.

Among the priests that often passed by the tea-house on their way to the monastery, were some who were young and handsome.

It was the rule of the monastery that none of the bonzes should drink saké (wine) eat fish or meat, or even stop at the tea-houses to talk with women. But one young bonze named “Lift-the-Kettle” (after a passage in the Sanscrit classics) had rigidly kept the rules. Fish had never passed his mouth; and as for saké, he did not know even its taste. He was very studious and diligent. Every day he learned ten new Chinese characters. He had already read several of the sacred sutras, had made a good beginning in Sanskrit, knew the name of every idol in the temple of the 3,333 images in Kioto, had twice visited the sacred shrine of the Capital, and had uttered the prayer “Namu miō ho ren gé kiō,” (“Glory be to the sacred lotus of the law”), counting it on his rosary, five hundred thousand times. For sanctity and learning he had no peer among the young neophytes of the bonzerie.

Alas for “Lift-the-Kettle!”. One day, after returning from a visit to a famous shrine in the Kuanto, (Eastern Japan), as he was passing the tea-house, he caught sight of Kiyohimé, (the “lady” or “princess” Kiyo), and from that moment his pain of heart began. He returned to his bed of mats, but not to sleep. For days he tried to stifle his passion, but his heart only smouldered away like an incense-stick.

Before many days he made a pretext for again passing the house. Hopelessly in love, without waiting many days he stopped and entered the tea-house.

His call for refreshments was answered by Kiyohimé herself!

As fire kindles fire, so priest and maiden were now consumed in one flame of love. To shorten a long story, “Lift-the-Kettle” visited the inn oftener and oftener, even stealing out at night to cross the river and spend the silent hours with his love.

So passed several months, when suddenly a change come over the young bonze. His conscience began to trouble him for breaking his vows. In the terrible conflict between principle and passion, the soul of the priest was tossed to and fro like the feathered seed-ball of a shuttlecock.

But conscience was the stronger, and won.

He resolved to drown his love and break off his connection with the girl. To do it suddenly, would bring grief to her and a scandal both on her family and the monastery. He must do it gradually to succeed at all.

Ah! how quickly does the sensitive love-plant know the finger-tip touch of cooling passion! How quickly falls the silver column in the crystal tube, at the first breath of the heart’s chill even though the words on the lip are warm! Kiyohimé marked the ebbing tide of her lover’s regard, and then a terrible resolve of evil took possession of her soul. From that time forth, she ceased to be a pure and innocent and gentle virgin. Though still in maiden form and guise, she was at heart a fox, and as to her nature she might as well have worn the bushy tail of the sly deceiver. She resolved to win over her lover, by her importunities, and failing in this, to destroy him by sorcery.

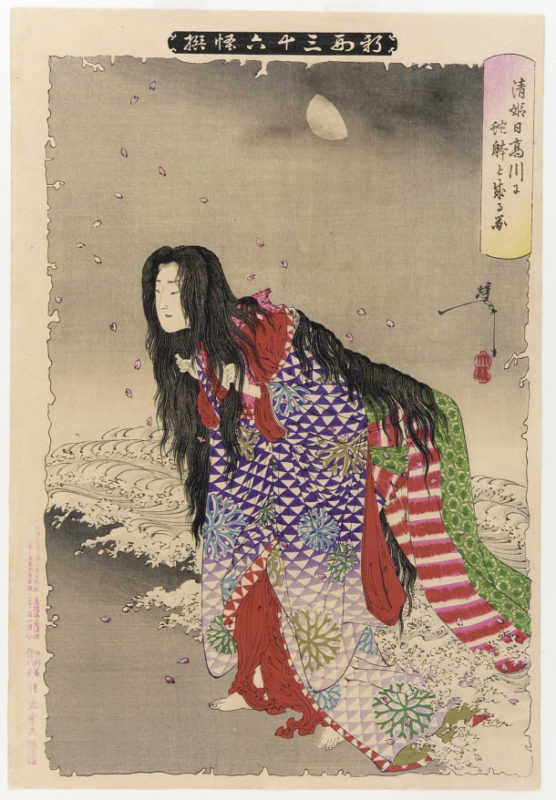

One night she sat up until two o’clock in the morning, and then, arrayed only in a white robe, she went out to a secluded part of the mountain where in a lonely shrine stood a hideous scowling image of Fudo, who holds the sword of vengeance and sits clothed in fire. There she called upon the god to change her lover’s heart or else destroy him.

Thence, with her head shaking, and eyes glittering with anger like the orbs of a serpent, she hastened to the shrine of Kampira, whose servants are the long-nosed sprites, who have the power of magic and of teaching sorcery. Standing in front of the portal she saw it hung with votive tablets, locks of hair, teeth, various tokens of vows, pledges and marks of sacrifice, which the devotees of the god had hung up. There, in the cold night air she asked for the power of sorcery, that she might be able at will to transform herself into the terrible ja,—the awful dragon-serpent whose engine coils are able to crack bones, crush rocks, melt iron or root up trees, and which are long enough to wind round a mountain.

It would be too long to tell how this once pure and happy maiden, now turned to an avenging demon went out nightly on the lonely mountains to practice the arts of sorcery. The mountain-sprites were her teachers, and she learned so diligently that the chief goblin at last told her she would be able, without fail, to transform herself when she wished.

The dreadful moment was soon to come. The visits of the once lover-priest gradually became fewer and fewer, and were no longer tender hours of love, but were on his part formal interviews, while Kiyohimé became more importunate than ever. Tears and pleadings were alike useless, and finally one night as he was taking leave, the bonze told the maid that he had paid his last visit. Kiyohimé then utterly forgetting all womanly delicacy, became so urgent that the bonze tore himself away and fled across the river. He had seen the terrible gleam in the maiden’s eyes, and now terribly frightened, hid himself under the great temple bell.

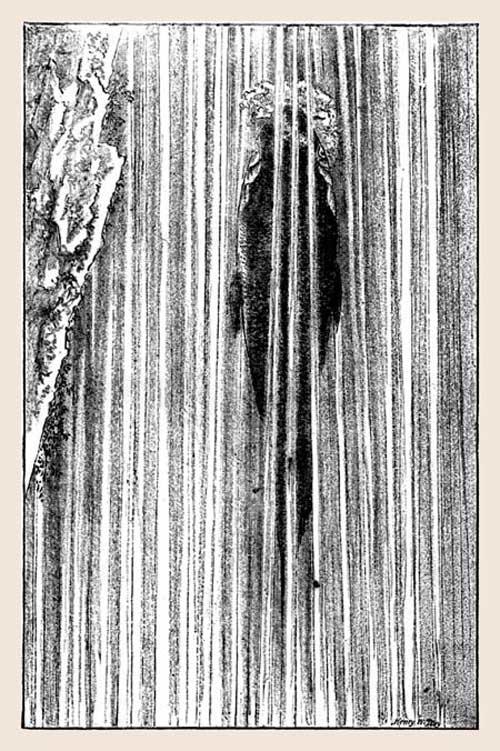

Forthwith Kiyohimé, seeing the awful moment had come, pronounced the spell of incantation taught her by the mountain spirit, and raised her T-shaped wand. In a moment her fair head and lovely face, body, limbs and feet lengthened out, disappeared, or became demon-like, and a fire-darting, hissing-tongued serpent, with eyes like moons trailed over the ground towards the temple, swam the river, and scenting out the track of the fugitive, entered the belfry, cracking the supporting columns made of whole tree-trunks into a mass of ruins, while the bell fell to the earth with the cowering victim inside.

Then began the winding of the terrible coils round and round the metal, as with her wand of sorcery in her hands, she mounted the bell. The glistening scales, hard as iron, struck off sparks as the pressure increased. Tighter and tighter they were drawn, till the heat of the friction consumed the timbers and made the metal glow hot like fire.

Vain was the prayer of priest, or spell of rosary, as the bonzes piteously besought great Buddha to destroy the demon. Hotter and hotter grew the mass, until the ponderous metal melted down into a hissing pool of scintillating molten bronze; and soon, man within and serpent without, timber and tiles and ropes were nought but a few handfuls of white ashes.

Reference

Griffis, William Elliot (1887) Japanese Fairy World. London: Trubner and Co.