This week, we finish this folklore series with one more from William Griffis. This time we meet a dragon. As before, this version retains Griffis’s original text. I also included Griffis’s commentary.

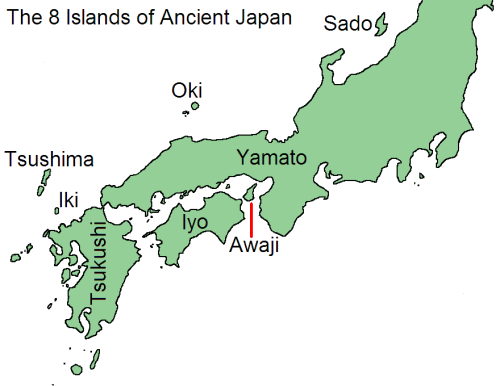

Soon after her arrival at home, the empress Jingu gave birth to a son, whom she named Ojin. He was one of the fairest children ever born of an imperial mother, and was very wise and wonderful even when an infant. He was a great favorite of Takénouchi, the prime minister of the empress. As he grew up, he was full of the Yamato Damashii, or the spirit of unconquerable Japan.This Takénouchi was a very venerable old man, who was said to be three hundred and sixty years old. He had been the counselor of five mikados. He was very tall, and as straight as an arrow, when other old men were bent like a bow. He served as a general in war and a civil officer in peace. For this reason he always kept on a suit of armor under his long satin and damask court robes. He wore the bear-skin shoes and the tiger-skin scabbard which were the general’s badge of rank, and also the high cap and long fringed strap hanging from the belt, which marked the court noble. He had moustaches, and a long beard fell over his breast like a foaming waterfall, as white as the snows on the branches of the pine trees of Ibuki mountain.

Now the empress, as well as Takénouchi, wished the imperial infant Ojin to live long, be wise and powerful, become a mighty warrior, be invulnerable in battle, and to have control over the tides and the ocean as his mother once had. To do this it was necessary to get back the Tide Jewels.

So Takénouchi took the infant Ojin on his shoulders, mounted the imperial war-barge, whose sails were of gold-embroidered silk, and bade his rowers put out to sea. Then standing upright on the deck, he called on Kai Riu O to come up out of the deep and give back the Tide Jewels to Ojin.

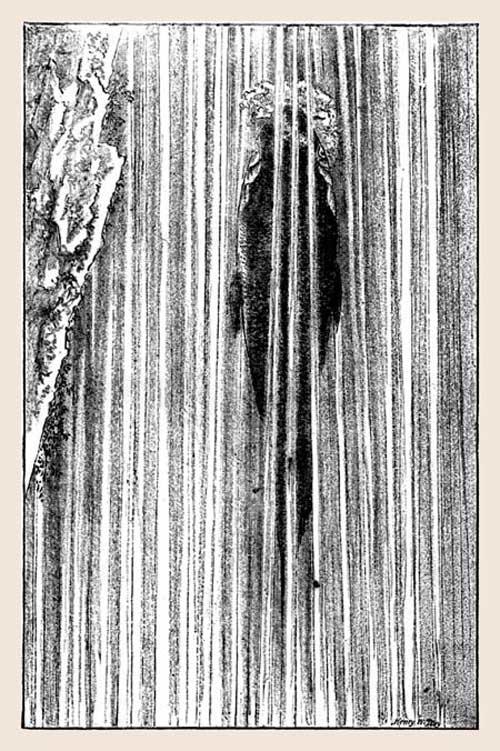

At first there was no sign on the waves that Kai Riu O heard. The green sea lay glassy in the sunlight, and the waves laughed and curled above the sides of the boat. Still Takénouchi listened intently and waited reverently. He was not long in suspense. Looking down far under the sparkling waves, he saw the head and fiery eyes of a dragon mounting upward. Instinctively he clutched his robe with his right hand, and held Ojin tightly on his shoulder, for this time not Isora, but the terrible Kai Riu O himself was coming.

What a great honor! The sea-king’s servant, Isora, had appeared to a woman, the empress Jingu, but to her son, the Dragon King of the World Under the Sea deigned to come in person.

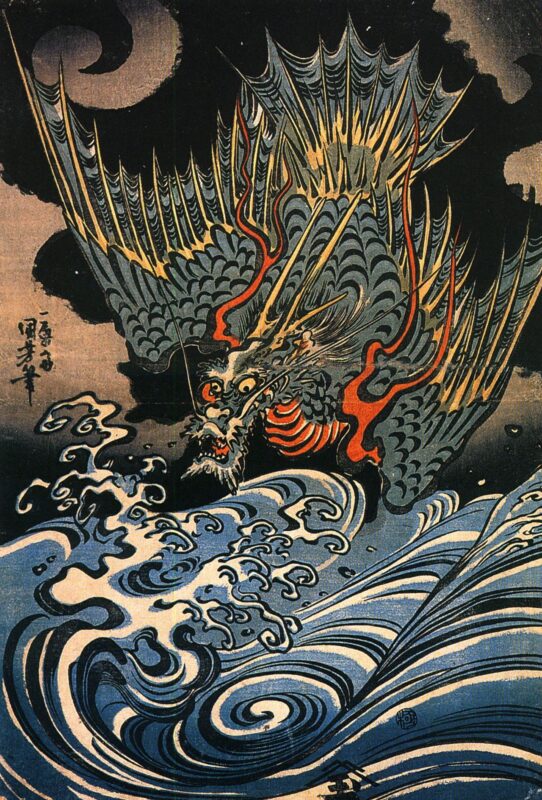

The waters opened; the waves rolled up, curled, rolled into wreaths and hooks and drops of foam, which flecked the dark green curves with silvery bells. First appeared a living dragon with fire-darting eyes, long flickering moustaches, glittering scales of green all ruffled, with terrible spines erect, and the joints of the fore-paws curling out jets of red fire. This living creature was the helmet of the Sea King. Next appeared the face of awful majesty and stern mien, as if with reluctant condescension, and then the jewel robes of the monarch. Next rose into view a huge haliotis shell, in which, on a bed of rare gems from the deep sea floor, glistened, blazed and flashed the two Jewels of the Tides.

Then the Dragon-King spoke, saying:

“Quick, take this casket, I deign not to remain long in this upper world of mortals. With these I endow the imperial prince of the Heavenly line of the mikados of the Divine country. He shall be invulnerable in battle. He shall have long life. To him I give power over sea and land. Of this, let these Tide-Jewels be the token.”

Hardly were these words uttered when the Dragon-King disappeared with a tremendous splash. Takénouchi standing erect but breathless amid the crowd of rowers who, crouching at the boat’s bottom had not dared so much as to lift up their noses, waited a moment, and then gave the command to turn the prow to the shore.

Ojin grew up and became a great warrior, invincible in battle and powerful in peace. He lived to be one hundred and eleven years old, and was next to the last of the long lived mikados of Everlasting Great Japan.

To this day Japanese soldiers honor him as the patron of war, and pray to him as the ruler of battle.

When the Buddhist priests came to Japan they changed his name to Hachiman Dai Bosatsu, or the “Great Buddha of the Eight Banners.” On many a hill and in many a village of Japan may still be seen a shrine to his honor. Often when a soldier comes back from war, he will hang up a tablet or picture-frame, on which is carved a painting or picture of the two-edged short sword like that which Ojin carried. Many of the old soldiers who fought in armor wore a little silver sword of Ojin set as a frontlet to their helmets, for a crest of honor. On gilded or lacquered Japanese cabinets and shrines, and printed on their curious old, and new greenback paper money, are seen the blazing Jewels of the Tides. On their gold and silver coins the coiled dragon clutches in his claws the Jewels of the Ebbing and the Flowing Tide. One of the iron-clad war ships of the imperial Japanese navy, on which floats proudly the red sun-banner of the Empire of the Rising Sun, is named Kōgō (Empress) after the Amazon empress who in the third century carried the arms of the Island Empire into the main land of Asia, and won victory by her mastery over the ebbing and the flowing tides.

Reference

Griffis, William Elliot (1887). Japanese Fairy World. London: Trubner & Co. Ludgate Hill.