In the village of Iwahara, in the province of Shinshiu, there dwelt a family which had acquired considerable wealth in the wine trade. On some auspicious occasion it happened that a number of guests were gathered together at their house, feasting on wine and fish; and as the wine-cup went round, the conversation turned upon foxes. Among the guests was a certain carpenter, Tokutarô by name, a man about thirty years of age, of a stubborn and obstinate turn, who said—

“Well, sirs, you’ve been talking for some time of men being bewitched by foxes; surely you must be under their influence yourselves, to say such things. How on earth can foxes have such power over men? At any rate, men must be great fools to be so deluded. Let’s have no more of this nonsense.”

Upon this a man who was sitting by him answered—

“Tokutarô little knows what goes on in the world, or he would not speak so. How many myriads of men are there who have been bewitched by foxes? Why, there have been at least twenty or thirty men tricked by the brutes on the Maki Moor alone. It’s hard to disprove facts that have happened before our eyes.”

“You’re no better than a pack of born idiots,” said Tokutarô. “I will engage to go out to the Maki Moor this very night and prove it. There is not a fox in all Japan that can make a fool of Tokutarô.”

“Thus he spoke in his pride; but the others were all angry with him for boasting, and said—

“If you return without anything having happened, we will pay for five measures of wine and a thousand copper cash worth of fish; and if you are bewitched, you shall do as much for us.”

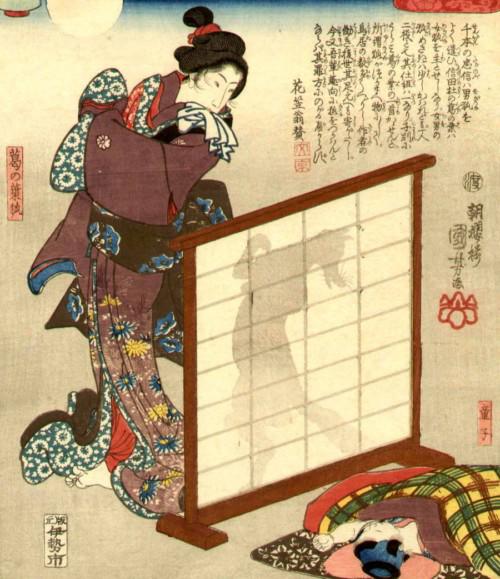

Tokutarô took the bet, and at nightfall set forth for the Maki Moor by himself. As he neared the moor, he saw before him a small bamboo grove, into which a fox ran; and it instantly occurred to him that the foxes of the moor would try to bewitch him. As he was yet looking, he suddenly saw the daughter of the headman of the village of Upper Horikané, who was married to the headman of the village of Maki.

“Pray, where are you going to, Master Tokutarô?” said she.

“I am going to the village hard by.”

“Then, as you will have to pass my native place, if you will allow me, I will accompany you so far.”

Tokutarô thought this very odd, and made up his mind that it was a fox trying to make a fool of him; he accordingly determined to turn the tables on the fox, and answered— “It is a long time since I have had the pleasure of seeing you; and as it seems that your house is on my road, I shall be glad to escort you so far.”

With this he walked behind her, thinking he should certainly see the end of a fox’s tail peeping out; but, look as he might, there was nothing to be seen. At last they came to the village of Upper Horikané; and when they reached the cottage of the girl’s father, the family all came out, surprised to see her.

“Oh dear! oh dear! here is our daughter come: I hope there is nothing the matter.”

And so they went on, for some time, asking a string of questions.

In the meanwhile, Tokutarô went round to the kitchen door, at the back of the house, and, beckoning out the master of the house, said—

“The girl who has come with me is not really your daughter. As I was going to the Maki Moor, when I arrived at the bamboo grove, a fox jumped up in front of me, and when it had dashed into the grove it immediately took the shape of your daughter, and offered to accompany me to the village; so I pretended to be taken in by the brute, and came with it so far.”

On hearing this, the master of the house put his head on one side, and mused a while; then, calling his wife, he repeated the story to her, in a whisper.

But she flew into a great rage with Tokutarô, and said—

“This is a pretty way of insulting people’s daughters. The girl is our daughter, and there’s no mistake about it. How dare you invent such lies?”

“Well,” said Tokutarô, “you are quite right to say so; but still there is no doubt that this is a case of witchcraft.”

Seeing how obstinately he held to his opinion, the old folks were sorely perplexed, and said—

“What do you think of doing?”

“Pray leave the matter to me: I’ll soon strip the false skin off, and show the beast to you in its true colours. Do you two go into the store-closet, and wait there.”

With this he went into the kitchen, and, seizing the girl by the back of the neck, forced her down by the hearth.

“Oh! Master Tokutarô, what means this brutal violence? Mother! father! help!”

So the girl cried and screamed; but Tokutarô only laughed, and said—

“So you thought to bewitch me, did you? From the moment you jumped into the wood, I was on the look-out for you to play me some trick. I’ll soon make you show what you really are;” and as he said this, he twisted her two hands behind her back, and trod upon her, and tortured her; but she only wept, and cried—

“Oh! it hurts, it hurts!”

“If this is not enough to make you show your true form, I’ll roast you to death;” and he piled firewood on the hearth, and, tucking up her dress, scorched her severely.

“Oh! oh! this is more than I can bear;” and with this she expired.

The two old people then came running in from the rear of the house, and, pushing aside Tokutarô, folded their daughter in their arms, and put their hands to her mouth to feel whether she still breathed; but life was extinct, and not the sign of a fox’s tail was to be seen about her. Then they seized Tokutarô by the collar, and cried—

“On pretence that our true daughter was a fox, you have roasted her to death. Murderer! Here, you there, bring ropes and cords, and secure this Tokutarô!”

So the servants obeyed, and several of them seized Tokutarô and bound him to a pillar. Then the master of the house, turning to Tokutarô, said—

“You have murdered our daughter before our very eyes. I shall report the matter to the lord of the manor, and you will assuredly pay for this with your head. Be prepared for the worst.”

And as he said this, glaring fiercely at Tokutarô, they carried the corpse of his daughter into the store-closet. As they were sending to make the matter known in the village of Maki, and taking other measures, who should come up but the priest of the temple called Anrakuji, in the village of Iwahara, with an acolyte and a servant, who called out in a loud voice from the front door—

“Is all well with the honourable master of this house? I have been to say prayers to-day in a neighbouring village, and on my way back I could not pass the door without at least inquiring after your welfare. If you are at home, I would fain pay my respects to you.”

As he spoke thus in a loud voice, he was heard from the back of the house; and the master got up and went out, and, after the usual compliments on meeting had been exchanged, said—

“I ought to have the honour of inviting you to step inside this evening; but really we are all in the greatest trouble, and I must beg you to excuse my impoliteness.”

“Indeed! Pray, what may be the matter?” replied the priest. And when the master of the house had told the whole story, from beginning to end, he was thunderstruck, and said—

“Truly, this must be a terrible distress to you.” Then the priest looked on one side, and saw Tokutarô bound, and exclaimed, “Is not that Tokutarô that I see there?”

“Oh, your reverence,” replied Tokutarô, piteously, “it was this, that, and the other: and I took it into my head that the young lady was a fox, and so I killed her. But I pray your reverence to intercede for me, and save my life;” and as he spoke, the tears started from his eyes.

“To be sure,” said the priest, “you may well bewail yourself; however, if I save your life, will you consent to become my disciple, and enter the priesthood?”

“Only save my life, and I’ll become your disciple with all my heart.”

When the priest heard this, he called out the parents, and said to them—

“It would seem that, though I am but a foolish old priest, my coming here to-day has been unusually well timed. I have a request to make of you. Your putting Tokutarô to death won’t bring your daughter to life again. I have heard his story, and there certainly was no malice prepense on his part to kill your daughter. What he did, he did thinking to do a service to your family; and it would surely be better to hush the matter up. He wishes, moreover, to give himself over to me, and to become my disciple.”

“It is as you say,” replied the father and mother, speaking together. “Revenge will not recall our daughter. Please dispel our grief, by shaving his head and making a priest of him on the spot.”

“I’ll shave him at once, before your eyes,” answered the priest, who immediately caused the cords which bound Tokutarô to be untied, and, putting on his priest’s scarf, made him join his hands together in a posture of prayer. Then the reverend man stood up behind him, razor in hand, and, intoning a hymn, gave two or three strokes of the razor, which he then handed to his acolyte, who made a clean shave of Tokutarô’s hair. When the latter had finished his obeisance to the priest, and the ceremony was over, there was a loud burst of laughter; and at the same moment the day broke, and Tokutarô found himself alone, in the middle of a large moor. At first, in his surprise, he thought that it was all a dream, and was much annoyed at having been tricked by the foxes. He then passed his hand over his head, and found that he was shaved quite bald. There was nothing for it but to get up, wrap a handkerchief round his head, and go back to the place where his friends were assembled.

“Hallo, Tokutarô! so you’ve come back. Well, how about the foxes?”

“Really, gentlemen,” replied he, bowing, “I am quite ashamed to appear before you.”

Then he told them the whole story, and, when he had finished, pulled off the kerchief, and showed his bald pate.

“What a capital joke!” shouted his listeners, and amid roars of laughter, claimed the bet of fish, and wine. It was duly paid; but Tokutarô never allowed his hair to grow again, and renounced the world, and became a priest under the name of Sainen.

There are a great many stories told of men being shaved by the foxes; but this story came under the personal observation of Mr. Shôminsai, a teacher of the city of Yedo, during a holiday trip which he took to the country where the event occurred; and I have recorded it in the very selfsame words in which he told it to me.

—

This tales starts are pretty gruesome with Tokutaro roasting a young girl alive. Then it flips expectations on its head. In Japanese folklore, foxes (or kitsune – きつね) are mischievous creatures and messengers of the gods. In this story, foxes seem to be both. They are both tricksters and a spiritual call for the men they trick. Tokutaro gives up a worldly life and becomes a priest because of the lesson he learned from his encounter with the foxes.

If you want to learn more about kitsune, I wrote a book about them: Come and Sleep: The Folklore of the Japanese Fox.

References

Milford, A. (1871). Tales of Old Japan. http://ftp.utexas.edu/projectgutenberg/1/3/0/1/13015/13015-h/13015-h.htm