If you read Japanese folklore, you notice how different the endings seem against Western stories. In most Japanese folktales, people die in the end. Happily-ever-after endings stand out because of their rarity. Of course, most of Grimm’s fairy tales end on a similar note. The children’s versions of Grimm’s most of us in the West grew up with, such as Cinderella and Red Riding Hood, end on a happily-ever-after and are rather tame. The compilations usually lack the more gruesome stories like “The Wolf and the Seven Young Children”:

There was once an old goat who had seven little ones, and was as fond of them as ever mother was of her children. One day she had to go into the wood to fetch food for them, so she called them all round her. “Dear children,” said she, “I am going out into the wood; and while I am gone, be on your guard against the wolf, for if he were once to get inside he would eat you up, skin, bones, and all. The wretch often disguises himself, but he may always be known by his hoarse voice and black paws.” – “Dear mother,” answered the kids, “you need not be afraid, we will take good care of ourselves.” And the mother bleated good-bye, and went on her way with an easy mind.

It was not long before some one came knocking at the house-door, and crying out: “Open the door, my dear children, your mother is come back, and has brought each of you something.” But the little kids knew it was the wolf by the hoarse voice. “We will not open the door,” cried they; “you are not our mother, she has a delicate and sweet voice, and your voice is hoarse; you must be the wolf.” Then off went the wolf to a shop and bought a big lump of chalk, and ate it up to make his voice soft. And then he came back, knocked at the house-door, and cried: “Open the door, my dear children, your mother is here, and has brought each of you something.” But the wolf had put up his black paws against the window, and the kids seeing this, cried out, “We will not open the door; our mother has no black paws like you; you must be the wolf.” The wolf then ran to a baker. “Baker,” said he, “I am hurt in the foot; pray spread some dough over the place.” And when the baker had plastered his feet, he ran to the miller. “Miller,” said he, “strew me some white meal over my paws.” But the miller refused, thinking the wolf must be meaning harm to some one. “If you don’t do it,” cried the wolf, “I’ll eat you up!” And the miller was afraid and did as he was told. And that just shows what men are.

And now came the rogue the third time to the door and knocked. “Open, children!” cried he. “Your dear mother has come home, and brought you each something from the wood.” – “First show us your paws,” said the kids, “so that we may know if you are really our mother or not.” And he put up his paws against the window, and when they saw that they were white, all seemed right, and they opened the door. And when he was inside they saw it was the wolf, and they were terrified and tried to hide themselves. One ran under the table, the second got into the bed, the third into the oven, the fourth in the kitchen, the fifth in the cupboard, the sixth under the sink, the seventh in the clock-case. But the wolf found them all, and gave them short shrift; one after the other he swallowed down, all but the youngest, who was hid in the clock-case. And so the wolf, having got what he wanted, strolled forth into the green meadows, and laying himself down under a tree, he fell asleep.

Not long after, the mother goat came back from the wood; and, oh! what a sight met her eyes! the door was standing wide open, table, chairs, and stools, all thrown about, dishes broken, quilt and pillows torn off the bed. She sought her children, they were nowhere to be found. She called to each of them by name, but nobody answered, until she came to the name of the youngest. “Here I am, mother,” a little voice cried, “here, in the clock case.” And so she helped him out, and heard how the wolf had come, and eaten all the rest. And you may think how she cried for the loss of her dear children.

At last in her grief she wandered out of doors, and the youngest kid with her; and when they came into the meadow, there they saw the wolf lying under a tree, and snoring so that the branches shook. The mother goat looked at him carefully on all sides and she noticed how something inside his body was moving and struggling. Dear me! thought she, can it be that my poor children that he devoured for his evening meal are still alive? And she sent the little kid back to the house for a pair of shears, and needle, and thread. Then she cut the wolf’s body open, and no sooner had she made one snip than out came the head of one of the kids, and then another snip, and then one after the other the six little kids all jumped out alive and well, for in his greediness the rogue had swallowed them down whole. How delightful this was! so they comforted their dear mother and hopped about like tailors at a wedding. “Now fetch some good hard stones,” said the mother, “and we will fill his body with them, as he lies asleep.” And so they fetched some in all haste, and put them inside him, and the mother sewed him up so quickly again that he was none the wiser.

When the wolf at last awoke, and got up, the stones inside him made him feel very thirsty, and as he was going to the brook to drink, they struck and rattled one against another. And so he cried out:

“What is this I feel inside me

Knocking hard against my bones?

How should such a thing betide me!

They were kids, and now they’re stones.”So he came to the brook, and stooped to drink, but the heavy stones weighed him down, so he fell over into the water and was drowned. And when the seven little kids saw it they came up running. “The wolf is dead, the wolf is dead!” they cried, and taking hands, they danced with their mother all about the place.

Japanese folktales have a similar gruesome note to them. Many deal with death or injuries. We think folktales were meant for children, but people of all ages enjoyed them. They taught moral lessons, but they also challenged the social status quo of their time periods. People weren’t as separated from death as we are now. They killed animals for dinner. They experienced the death of children. War also claimed people. Their closeness with death explains why so many Japanese folktales and Grimm’s folktales end with it.

After all, that’s how we all end our life stories.

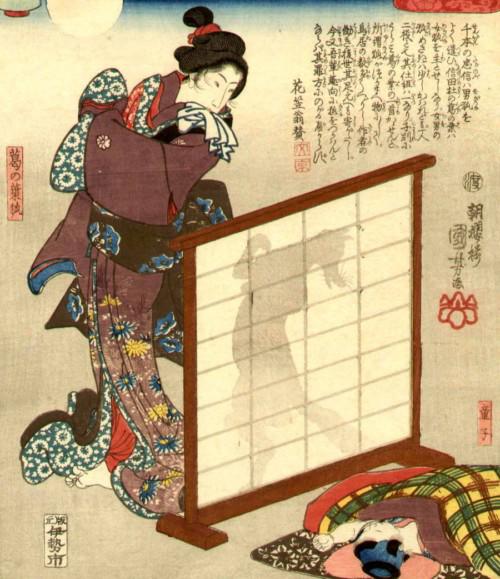

Death was a fact of life. And despite the magic and creatures, folktales reflected life. In fact, folktales contained observations about wildlife, plants, and the natural world couched in stories designed to aid memory. For example, kitsune stories involve foxes living on the borders of fields and forests. They blessed farmers with good harvests (by eating critters that ate crops). Foxes could shapeshift into women who were dedicated to their children, reflecting the fox’s dedication to her kits.

In fox stories, the fox usually left her human family. This type of death–and separation can be seen as death–reinforced the difference between the human world and the natural world, but it also meditated on separation as a part of life. Our relationships all end either through death or circumstances. Yet, those relationships can change our lives and the future. Pay attention to the ending of the first fox story of Japanese history: “Come and Sleep.” If you want to learn more about the Japanese fox, I look at her in some depth in my book, “Come and Sleep.”

In the reign of Emperor Kinmei (that is, Amekuni-oshihiraki-hironiwa no mikoto, the emperor who resided at the Palace of Kanazashi in Shikishima [510-571 AD]), a man from Ouno district of Mino province set out on horseback in search of a good wife. In a field he came across a pretty and responsive girl. He winked at her and asked, “Where are you going, Miss?” “I am looking for a good husband,” she answered. So he asked, “Will you be my wife?” and, when she agreed, he took her to his house and married her.

Before long she became pregnant and gave birth to a boy. At the same time their dog also gave birth to a puppy, it being the fifteenth of the twelfth month. This puppy barked constantly at the mistress and seemed fierce and ready to bite. She became so frightened that she asked her husband to beat the dog to death. But he felt sorry for the dog and could not bear to kill it.

In the second or third month, when the annual quota of rice [that is, the rice due to be sent to the capitol as taxes] was hulled, she went to the place where the female servants were pounding rice in a mortar to give them some refreshments. The dog, seeing her, ran after her barking and almost bit her. Startled and terrified, she suddenly changed into a wild fox and jumped up on top of the hedge.

Having seen this, the man said, “Since a child was born between us, I cannot forget you. Please come always and sleep with me.” She acted in accordance with her husband’s words and came and slept with him. For this reason she was named “Kitsune” meaning “come and sleep.”

Slender and beautiful in her red skirt, she would rustle away from her husband, whereupon he sang of his love for his wife:

Love fills me completely

After a moment of reunion.

Alas! She is gone.The man named his child Kitsune, which became the child’s surname—Kitsune no atae. The child, famous for his enormous strength, could run as fast as a bird flies. He is the ancestor of the Kitsune-no-atae family in Mino province.

Although the ending of this story is sad–Kitsune cannot stay with her family–the fox founds a family. Sorrow runs through the endings of most folktales, contrasting to the sanitized folktales of Western childhood. Japanese culture (and ancient culture in general) embraced sorrow; whereas, we moderns tend to avoid sorrow. Sad endings inoculate against the sorrows we inevitably encounter. They allow us to expect life to have a sorrowful flavor. And that flavor and expectation allows us to savor happiness.

Bittersweet endings like “Come and Sleep” point out how we don’t fully treasure our relationships until they end. The endings allow us to learn the lesson before we experience our own endings. In fact, story remains the best way for learning; we internalize the lesson as we experience the story.

Modern life has reversed the normalcy that categorized human thinking for most of history. Our obsessive avoidance of sorrow would be considered odd by those who told folktales. It can be considered a deficit of education, leaving us without the skills we need for life. In fact, after-anime depression can be a sign you lack coping skills and shows the stories are working toward helping you learn how make peace with sorrow. Our films often lack the educational aspects of folklore, falling on entertainment templates that lack observations of human behavior. Our movies end with “happily ever after.”

The endings of Japanese folktales can still teach us lessons and inoculate us against the reality of sorrow. Some anime taps into this cultural legacy, such as the ending of Samurai Champloo, but I’d like to see more stories avoid happily-ever-afters. A sorrowful or bittersweet endings can make a story more memorable while encouraging appreciation.

Reference

Grimm’s Fairy Tales 1. “The Wolf and the Seven Young Children.”

Nihon Ryouiki, I.2, “On Taking a Fox as a Wife and Bringing Forth a Child”

Hello

I have happily found (& bought) your book “Come and Sleep.” I am interested in learning about Japan’s myths & folktales, albeit finally finishing/completing (after ten years) Capcom’s game Okami.

Any suggestions on where I can find more info on the mythology of Shinto & the kami?

TYSM

KIM

Okami is a great game! Well, as an author I have to plug my collection of Japanese folklore: “Tales from Old Japan” (I will offer it on a free promotion starting June 17,2022). Shinto doesn’t really have scripture. It’s a system of practices and rituals that vary a bit by region.

With that in mind, I would recommend reading these books to learn more:

These should get you started. The Kojiki is the Book of Genesis for Japan. The other books touch on Shinto rituals and thoughts about kami.