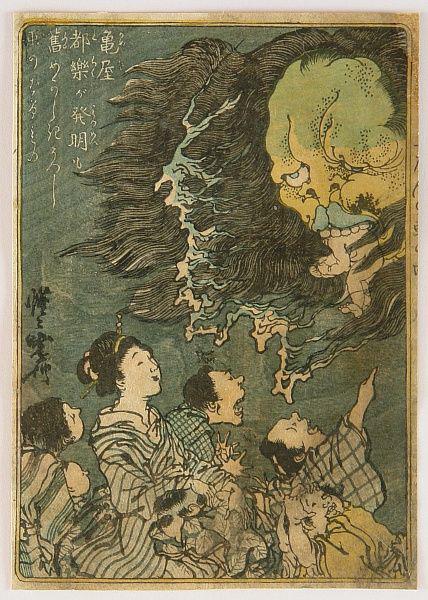

Now Yemma had under him a whole legion of oni, some green, some black, others blue as indigo, and others of a vermillion color, which he usually sent on ordinary errands.

But for so important an expedition he now called Shino a very cunning old fellow, and ordered him to kill or remove Daikoku out of the way.

Shino made his bow to his master, tightened his tiger-skin belt around his loins and set off.

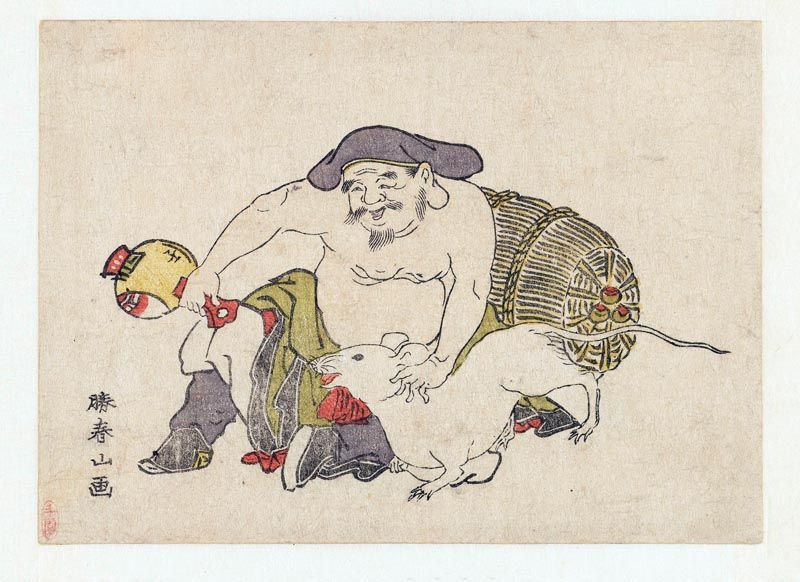

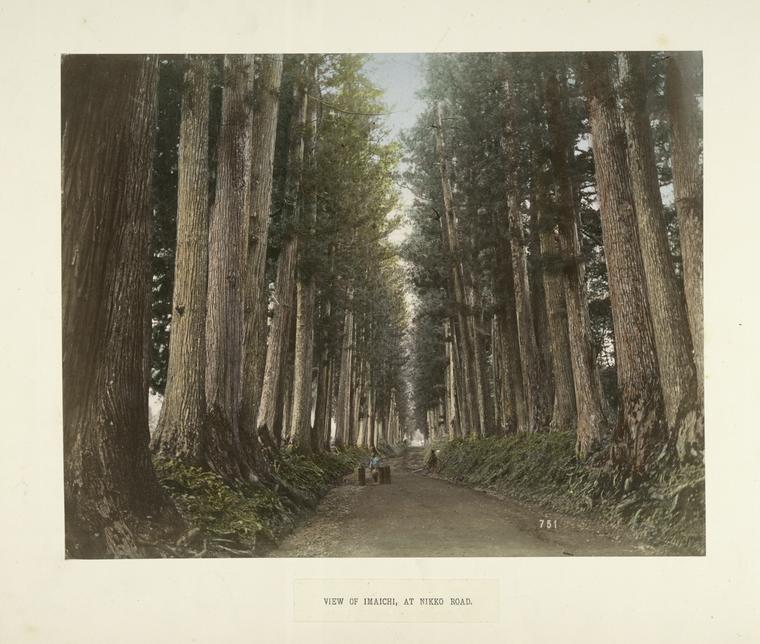

It was not an easy thing to find Daikoku, even though every one worshipped him. So the oni had to travel a long way, and ask a great many questions of people, and often lose his way before he got any clue. One day he met a sparrow who directed him to Daikoku’s palace, where among all his money-bags and treasure piled to the ceiling, the fat and loop-eared fellow was accustomed to sit eating daikon radish, and amuse himself with his favorite pets, the rats. Around him was stored in straw bags his rice which he considered more precious than money.

Entering the gate, the oni peeped about cautiously but saw no one. He went further on till he came to a large store house standing alone and built in the shape of a huge rice-measure. Not a door or window could be seen, but climbing up a narrow plank set against the top edge he peeped over, and there sat Daikoku.

The oni descended and got into the room. Then he thought it would be an easy thing to pounce upon Daikoku. He was already chuckling to himself over the prospect of such wealth being his own, when Daikoku squeaked out to his chief rat.

“Nedzumi san, (Mr. Rat) I feel some strange creature must be near. Go chase him off the premises.”

Away scampered the rat to the garden and plucked a sprig of holly with leaves full of thorns like needles. With this in his fore-paw, he ran at the oni, whacked him soundly, and stuck him all over with the sharp prickles.

The oni yelling with pain ran away as fast as he could run. He was so frightened that he never stopped until he reached Yemma’s palace, when he fell down breathless. He then told his master the tale of his adventure, but begged that he might never again be sent against Daikoku.

So the Buddhist idols finding they could not banish or kill Daikoku, agreed to recognize him, and so they made peace with him and to this day Buddhists and Shintōists alike worship the fat little god of wealth.

When people heard how the chief oni had been driven away by only a rat armed with holly, they thought it a good thing to keep off all oni. So ever afterward, even to this day, after driving out all the bad creatures with parched beans, they place sprigs of holly at their door-posts on New Year’s eve, to keep away the oni and all evil spirits.

People see oni as a type of demon. While this is mostly true, oni don’t have to be evil. In Japanese folklore, stories speak of honest oni. This story of Daikoku touches on this. Folklore classifies oni as a type of low-spirit kami (as opposed to the high spirit classification, which includes deities). Oni fall into their own classification. Today, people call oni yokai. Yokai umbrellas a wide range of folklore creatures: ghosts, demons, goblins, and various other spirits. However, it used to be a specific classification. Only corrupted human spirits belonged to this category. Oni have more in common with natural creatures like kappa than with yokai. In Japanese folklore, spirits and creatures can move from low level to high level if people venerate them. Some deities started as oni, but they graduated as people used rituals and veneration to tame the oni and channel his abilities to their benefit. These enshrined oni lose their oni classification and become kami. Conversely, kami can fall into the low spirit status if people forget them.

While few believe in demons and the like today, folklore reveals how people from different periods viewed their world. The fluidity of kami and oni across different periods reflects how people’s needs changed over time. Some deities lost favor because they no longer remained relevant. Some oni became deities because their stories and traits resonated. For those of us in the West, this fluidity strikes us odd. But all the different deities found across Shinto are all parts of a single Kami. They merely have different functions, similar to how fingers and elbows differ in function but remain a part of the body. This allows beliefs to be fluid without appearing to be fickle.

References

Griffis, William Elliot. Japanese Fairy World: Stories from the Wonder-Lore of Japan. London: Trubner & Co. Ludgate Hall. 1887.

Appreciate the re-telling of the folklore. Please keep it coming!

You might like a project my editor is working on. I re-told 177 Japanese folktales and compiled them into a single volume. The project aims at casual, modern readers who don’t want to slog through Victorian commentary. I hope the project will be finished by the holidays, but they are coming up fast now.