The Kojiki, which translates to “Records of Ancient Matters”, contains Japan’s native creation myths and other mythology. Like all mythology, it was considered both factually true and Truth through most of history. This translation comes from Basil Hall Chamberlain and dates to 1932. This excerpt includes the introduction of the first volume and Japan’s creation story. The story about the creation of Japan’s deities comes from a 1929 translation by Yaichiro Isobe. I include these two different translations to give you an idea of how these ancient texts can feel different depending on who is translating.

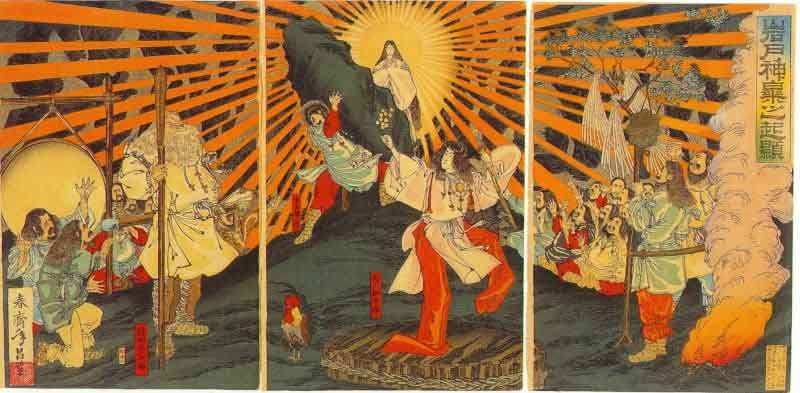

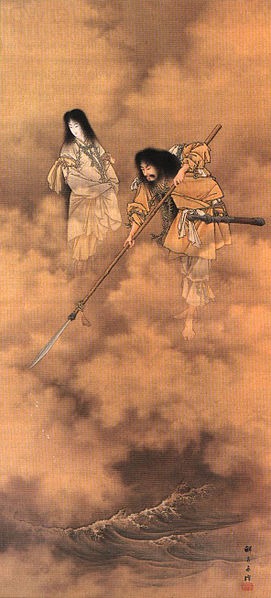

Hereupon all the ‘heavenly Deities commanded the two Deities His Augustness the Male-Who-Invites and her Augustness the Female-Who-Invites, ordering them to “make, consolidate, and give birth to this drifting land.” Granting to them a heavenly jewelled spear, they deigned to charge them. So the two Deities, standing upon the Floating Bridge of Heaven, pushed down the jewelled spear and stirred it, whereupon, when they had stirred the brine till it went curdle-curdle, and drew the spear up, the brine that dripped down from the end of the spear was piled up and became an island. This is the island of Onogoro.

Birth of the Eight Great Islands

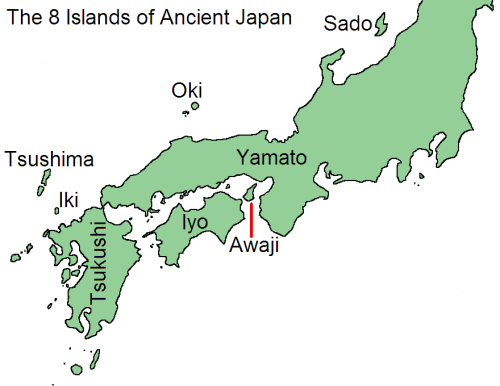

Hereupon the two Deities took counsel, saying: “The children to whom we have now given birth are not good. It will be best to announce this in the august place of the Heavenly Deities.” They ascended forthwith to Heaven and inquired of Their Augustnesses the Heavenly Deities. Then the Heavenly Deities commanded and found out by grand divination, and ordered them, saying: “They were not good because the woman spoke first. Descend back again and amend you words.” So thereupon descending back, they again when round the heavenly august pillar as before. Thereupon his Augustness the Male-Who-Invites spoke first: ” Ah! What a fair and lovely maiden!” Afterward; his younger sister Her Augustness the Female-Who-Invites spoke: “Ah! what a fair ad lovely youth!” In such way did they give birth to a child the Island of Ahaji, Honosawake. Next they gave birth to the Island of Futa-na in Iyo. This island has one body and four faces, and each face as a name. So the Land of Iyo is called Lovely Princess, the Land of Sanuki is called Prince Good Boiled Rice; the Land of Aha is called Princess of Great Food; the Land of Tosa is called Brave Good Youth. Next they gave birth to the Islands of Mitsugo near Oki, another nae for which is Heavenly Great Heart Youth. Next they gave birth to the island of Tsukushi. This island likewise has one body and four faces, and each face has a name. So the Land of Tsukushi is called White Sun Youth; the Land of Toyo is called Luxuriant Sun Youth; the Land of Hi is called Brave Sun Confronting Luxuriant Wonderous Lord Youth; the Land of Kumaso is called Brave Sun Youth.

Next they gave birth to the island of Iki, another name for which is Heaven’s One Pillar. Next they gave birth to the Island of Tsu, another name for which is Heavenly Hand net Good Princess. Next they gave birth to the Island of Sado. Next they gave birth to Great Yamato the Luxuriant Island of the Dragon Fly, another name for which is Heavenly August Sky Luxuriant Dragon fly Lord Youth. The name of Land of the Eight Great Islands therefore originated in these eight islands having been born first. After that, when they had returned, they gave birth to the Island of Ko in Kibi, another name for which is Brave Sun Direction Youth. Next they gave birth to the Island of Adzuki another name for which is Ohonudehime. Next they gave birth to he Island of Oho, another name for which is Tamaru-wake. Next they gave birth to he Island of Hime, another name for which is Heaven’s One Root. Next they gave birth to he Island of Chika, another name for which is Heavenly Great Male. Next they gave birth to he Island of Futago, another name for which is Heaven’s Two Houses.

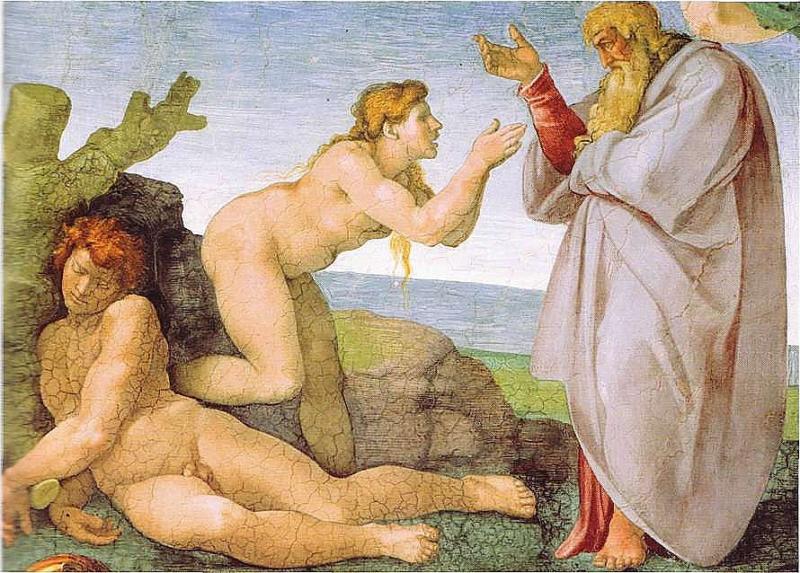

The Birth of the Deities

Having, thus, made a country from what had formerly been no more than a mere floating mass, the two Deities, Izanagi and Izanami, about begetting those deities destined to preside over the land, sea, mountains, rivers, trees, and herbs. Their first-born proved to be the sea-god, Owatatsumi-no-Kami. Next they gave birth to the patron gods of harbors, the male deity Kamihaya-akitsu-hiko having control of the land and the goddess Haya-akitsu-hime having control of the sea. These two latter deities subsequently gave birth to eight other gods.

Next Izanagi and Izanami gave birth to the wind-deity, Kami-Shinatsuhiko-no-Mikoto. At the moment of his birth, his breath was so potent that the clouds and mists, which had hung over the earth from the beginning of time, were immediately dispersed. In consequence, every corner of the world was filled with brightness. Kukunochi-no-Kami, the deity of trees, was the next to be born, followed by Oyamatsumi-no-Kami, the deity of mountains, and Kayanuhime-no-Kami, the goddess of the plains. . . .

The process of procreation had, so far, gone on happily, but at the birth of Kagutsuchi-no-Kami, the deity of fire, an unseen misfortune befell the divine mother, Izanami. During the course of her confinement, the goddess was so severely burned by the flaming child that she swooned away. Her divine consort, deeply alarmed, did all in his power to resuscitate her, but although he succeeded in restoring her to consciousness, her appetite had completely gone. Izanagi, thereupon and with the utmost loving care, prepared for her delectation various tasty dishes, but all to no avail, because whatever she swallowed was almost immediately rejected. It was in this wise that occurred the greatest miracle of all. From her mouth sprang Kanayama-biko and Kanayama-hime, respectively the god and goddess of metals, whilst from other parts of her body issued forth Haniyasu-hiko and Haniyasu-hime, respectively the god and goddess of earth. Before making her “divine retirement,” which marks the end of her earthly career, in a manner almost unspeakably miraculous she gave birth to her last-born, the goddess Mizuhame-no-Mikoto. Her demise marks the intrusion of death into the world. Similarly the corruption of her body and the grief occasioned by her death were each the first of their kind.

By the death of his faithful spouse Izanagi was now quite alone in the world. In conjunction with her, and in accordance with the instructions of the Heavenly Gods, he had created and consolidated the Island Empire of Japan. In the fulfillment of their divine mission, he and his heavenly spouse had lived an ideal life of mutual love and cooperation. It is only natural, therefore, that her death should have dealt him a truly mortal blow.

He threw himself upon her prostrate form, crying: “Oh, my dearest wife, why art thou gone, to leave me thus alone? How could I ever exchange thee for even one child? Come back for the sake of the world, in which there still remains so much for both us twain to do.” In a fit of uncontrollable grief, he stood sobbing at the head of the bier. His hot tears fell like hailstones, and lo! out of the tear-drops was born a beauteous babe, the goddess Nakisawame-no-Mikoto. In deep astonishment he stayed his tears, a gazed in wonder at the new-born child, but soon his tears returned only to fall faster than before. It was thus that a sudden change came over his state of mind. With bitter wrath, his eyes fell upon the infant god of fire, whose birth had proved so fatal to his mother. He drew his sword, Totsuka-no-tsurugi, and crying in his wrath, “Thou hateful matricide,” decapitated his fiery offspring. Up shot a crimson spout of blood. Out of the sword and blood together arose eight strong and gallant deities. “What! more children?” cried Izanagi, much astounded at their sudden appearance, but the very next moment, what should he see but eight more deities born from the lifeless body of the infant firegod! They came out from the various parts of the body,–head, breast, stomach, hands, feet, and navel, and, to add to his astonishment, all of them were glaring fiercely at him. Altogether stupefied he surveyed the new arrivals one after another.

Meanwhile Izanami, for whom her divine husband pined so bitterly, had quitted this world for good and all and gone to the Land of Hades.

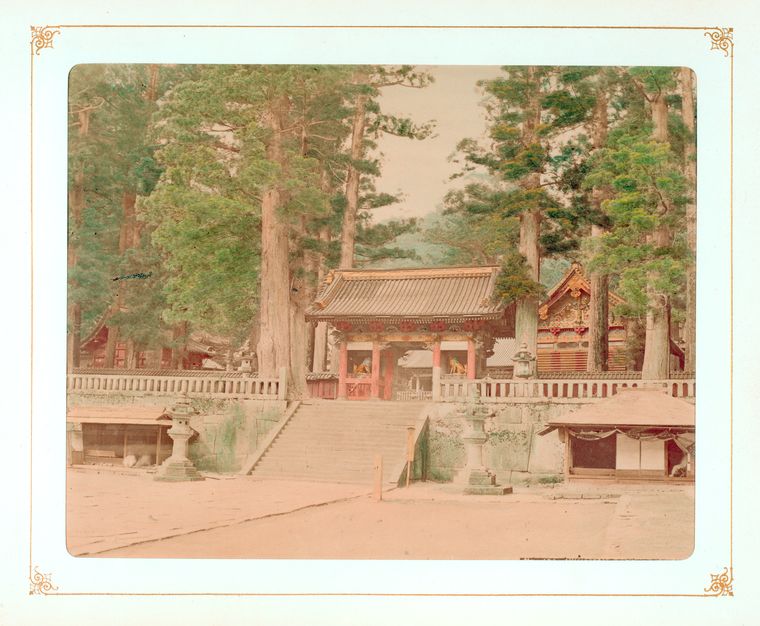

These creation stories, though strange to modern readers, speak of several truths. First, the story speaks with affection about the Japanese homeland. Much of Japanese history is characterized by a special affinity toward the land. Several times throughout Japanese history there were movements to restore the forests and other habitats. When everything has a spirit or god behind it, people tend to hold a respectful, reverent view of the environment and how it supports their lives. This can also be seen in Native American cultures. This myth and those like it suggest how we should retain our respect for the world around us and its resources. To do otherwise disrespects the divine and jeopardizes our ability to live.

The story about the gods’ births sets the stage for several reoccurring themes in Japanese literature and culture. Harmony is emphasized. Japanese culture places the quest for harmony between people and between people and nature in the center. Their honorific system grew out of this. The story shows how the decay of harmony and the reality of sorrow can lead to unintended consequences. In his grief, Izanagi kills his son, creating more sons and daughters in the process–much to his surprise. The story lays out a thread found throughout Japanese literature. The blissful, harmonious life Izanagi and Izanami shared couldn’t last. Izanami’s tragic death introduces sorrow to what was a happy story. Japanese literature enjoys balancing happiness with sorrow. Tragedy completes the story. Without sorrow, happiness cannot be understood. Few stories end “happily ever after” but this reflects a clear-eyed view of reality. Buddhism carries a similar thread. Buddhism stories focus on how suffering permeates our experiences. This overlap helped Shintoism (which is what these creation stories originate from) and Buddhism mingle. Whenever you read Japanese literature, you will see this interweaving of religions.

When you read some of these old translations, archaic Japanese is either depicted in Old English as you will see here or in Latin. Chamberlain’s excerpt contained a few sections of Latin that I translated for you. During the time these stories were written, the Imperial Court used a different dialect of Japanese than the rest of the country. This dialect fell out of style rather quickly but reappeared in literature. Imperial characters and gods spoke it to emphasize their separateness. The use of the language is similar to the Western use of Latin after the fall of Rome. Latin become the language of the Catholic Church and of educated noble elites. It was used to write court and religious documents. This similarity prompted some early translators to use Latin for Imperial Court Japanese. Unlike Latin, which still appears in academia and the Catholic Church, Imperial Court Japanese disappeared. A few remnants appear in Japanese language, but it lacks the cohesion that endures in Latin. You can still find vestiges of it in the speaking style in joseigo, the speaking style of Japan’s Lolita subculture, and with the Japanese Imperial family.

References

Chamberlain, B. (1939) Translation of Kojiki. Kobe: J.L. Thompson & Co.

Yaichiro, I. (1929) The Story of Ancient Japan or Tales from the Kojiki. San Kaku Sha.