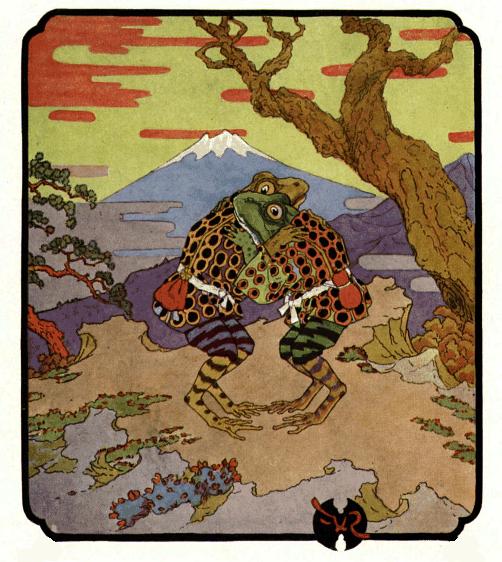

Between the years 1750 and 1760 there lived in Kyoto a great painter named Okyo-Maruyama Okyo. His paintings were such as to fetch high prices even in those days. Okyo had not only many admirers in consequence, but had also many pupils who strove to copy his style; among them was one named Rosetsu, who eventually became the best of all.

When first Rosetsu went to Okyo’s to study he was, without exception, the dullest and most stupid pupil that Okyo had ever had to deal with. His learning was so slow that pupils who had entered as students under Okyo a year and more after Rosetsu overtook him. He was one of those plodding but unfortunate youths who work hard, harder perhaps than most, and seem to go backwards as if the very gods were against them.

I have the deepest sympathy with Rosetsu. I myself became a bigger fool day by day as I worked; the harder I worked or tried to remember the more manifestly a fool I became.

Rosetsu, however, was in the end successful, having been greatly encouraged by his observations of the perseverance of a carp.

Many of the pupils who had entered Okyo’s school after Rosetsu had left, having become quite good painters. Poor Rosetsu was the only one who had made no progress whatever for three years. So disconsolate was he, and so little encouragement did his master offer, that at last, crestfallen and sad, he gave up the hopes he had had of becoming a great painter, and quietly left the school one evening, intending either to go home or to kill himself on the way. All that night he walked, and half-way into the next, when, tired out from want of sleep and of food, he flung himself down on the snow under the pine trees.

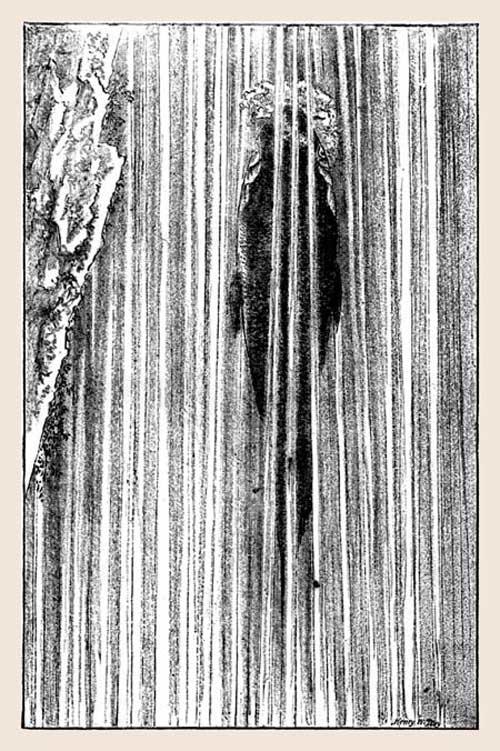

Some hours before dawn Rosetsu awoke, hearing a strange noise not thirty paces from him. He could not make it out, but sat up, listening, and glancing towards the place whence the sound—of splashing water—came.

As the day broke he saw that the noise was caused by a large carp, which was persistently jumping out of the water, evidently trying to reach a piece of sembei (a kind of biscuit made of rice and salt) lying on the ice of a pond near which Rosetsu found himself. For full three hours the fish must have been jumping thus unsuccessfully, cutting and bruising himself against the edges of the ice until the blood flowed and many scales had been lost

Rosetsu watched its persistency with admiration. The fish tried every imaginable device. Sometimes it would make a determined attack on the ice where the biscuit lay from underneath, by charging directly upwards; at other times it would jump high in the air, and hope that by falling on the ice bit by bit would be broken away, until it should be able to reach the sembei; and indeed the carp did thus break the ice, until at last he reached the prize, bleeding and hurt, but still rewarded for brave perseverance.

Rosetsu, much impressed, watched the fish swim off with the food, and reflected.

‘Yes,’ he said to himself: ‘this has been a moral lesson to me. I will be like this carp. I will not go home until I have gained my object. As long as there is breath in my body I will work to carry out my intention. I will labour harder than ever, and, no matter if I do not progress, I will continue in my efforts until I attain my end or die.’

After this resolve Rosetsu visited the neighbouring temple, and prayed for success; also he thanked the local deity that he had been enabled to see, through the carp’s perseverance, the line that a man should take in life.

Rosetsu then returned to Kyoto, and to his master, Okyo, told the story of the carp and of his determination.

Okyo was much pleased, and did his best for his backward pupil. This time Rosetsu progressed. He became a well-known painter, the best man Okyo ever taught, as good, in fact, as his master; and he ended by being one of Japan’s greatest painters.

Rosetsu took for crest the leaping carp.

References

Smith, Richard Gordon (1918) Ancient Tales and Folklore of Japan.