The Unfettered Mind contains essays and letters written by the Zen monk Takuan Soho, who was a friend and a teacher of Miyamoto Musashi. As Takuan neared death, he reportedly told his students: “Bury my body in the mountain behind the temple, cover it with dirt, and go home. Read no sutras, hold no ceremony. Receive no gifts from either monk or laity. Let the monks wear their robes, eat their meals, and carry on as a normal day.”

The essays in The Unfettered Mind delve into Takuan’s understanding of the mind (Duh! It’s in the title.) and how that understanding relates to swordsmanship. Swordsmanship, in turn, relates to life. Takuan’s essays assume a certain knowledge of Chinese classics and Zen philosophy. After all, he’s writing letters to specific people. Yet, under this density and sometimes tangled explanations lay gems of wisdom that are easy for anyone to understand:

Knowing what is evil but not refraining from it is a sickness of one’s own desires. Whether it be from a love of sensuality or self-indulgence, it is a matter of the mind desiring something.

Desire plays an important role into these essays. Desire is a result of being alive, Takuan argues. Let me give you his text and then unpack it. This bedrock argument falls deep into Buddhist thinking. And this ties into Takuan’s idea of an unfettered mind (which I will explain shortly).

Form, feeling, conception, volition, consciousness–then from consciousness back to form–if these are condensed over and over again, the linkage of the Five Skandhas according to the flow of the Twelve Links in the Chain of Existence, having received this body, begins with a single thought of our consciousness. Consciousness is, therefore, desire. This desire, this consciousness, gives rise to this body of the Five Skandhas.[…]Within this body solidified by desire is concealed the absolutely desireless and upright core of the mind.

As I said, Takuan assumes a lot of background knowledge. Basically, he argues the nature of being human is desire, yet within all the desires of the body rests a core that exists beyond desire. This core is what concerns him. A skandha is a collection of things we cling to and consider reality. Buddhism centers on the idea of attachment as the source for our suffering, so the five attachments–The Five Skandhas–are form, sensations, perceptions, thoughts, and consciousness. All of these are desires and have other desires associated with them. Perceptions, for example, desire us to hold firm to our opinions and the view them as truth.

All of this leads to his idea of an unfettered mind. For Takuan, an unfettered mind is a mind that doesn’t cling to anything. It moves naturally without stopping on any desire. An unfettered mind is a mind that has been trained so that it engages with life, letting the aspects of life come and go without clinging to them or resisting attachment to them. After all, to be human is to love and attach to people, animals, and things. Yet, we don’t have to cling to that attachment when it–as it always does–leaves.

Training the mind numbers among the things we shouldn’t cling to:

Because the mind is stained and stopped by things, we are warned against letting this happen, and are urged to seek after it and to return it to ourselves. This is the very first stage of training. We should be like the lotus which is unstained by the mud from which it rises. Even though the mud exists, we are not to be distressed by this. One makes his mind like the well-polished crystal that remains unstained even if put in the mud. He lets it go where it wishes. The effect of tightening up on the mind is to make it unfree. Bringing the mind under control is a thing done only in the beginning. If one remains this way all through life, in the end he will never reach the highest level. In fact, he will not rise above the lowest.

Our minds are well-polished crystals, separate from our thoughts yet also the source of our thoughts. Think of our mind as the source of a river. It is both different from the river and the river itself. You can’t separate where a spring starts and the river starts. We have to train our minds in order to polish them and, to comprehend the mind, we have to train the mind to focus. This is where meditation comes into play in Buddhism. Yet, after a certain point, this single-focus can become something we cling to. Something that holds you back. The ability to let things go, including training the mind, is what Takuan means by the phrase unfettered mind. It’s a mind that flows.

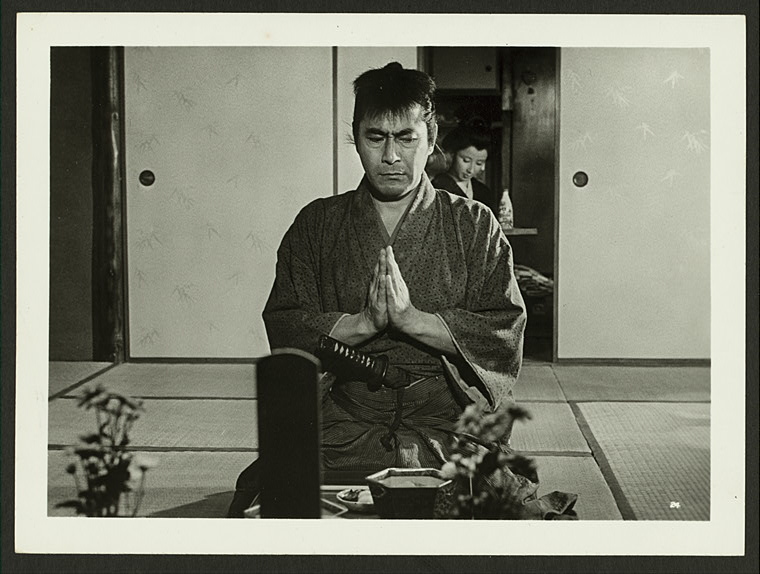

Now we are deep in the weeds of Buddhist thinking. Takuan had taught samurai who were concerned with swordsmanship. Yet this idea of an unfettered mind proves critical to being a good swordsman:

“Well, then, where does one put his mind?” I answered, “If you don’t put it anywhere, it will go to all parts of your body and extend throughout its entirety. In this way, when it enters your hand, it will realize the hand’s function. When it enters your foot, it will realize the foot’s function. When it enters your eye, it will realize the eye’s function. If you should decide on one place and put the mind there, it will be taken by that place and lose its function. If one thinks, he will be taken by his thoughts.”

In order to be a good swordsman, Takuan said, you have to keep a wide perception and not focus on any single aspect of a fight or of training. To tie this back to Takuan’s idea of desire: if a swordsman allows the desire to win, the desire to become stronger, the desire to become more skillful, he will fail to realize those desires because he is focusing the mind. The better way is to not focus on any single body part, to allow the mind not to desire, but to act naturally, moving across all the parts of the body. Takuan touches on the idea of muscle memory: of natural, trained movement. In the same way, training the mind allows it to move naturally as its been trained.

Nestled in all of this philosophy and deep analysis sits pointed advice and observations:

This is something nobody knows: from some offbeat inclination, one may be pulled along into bad habits and fall into evil. While you think no one knows about these faults, as “there is nothing as clear as that which is dimly seen,” if they are known in your own mind, they will also be known by heaven, earth, the gods, and the people.

Not understanding the principle of things, people often put on knowing faces and criticize those who do understand.

Applying Takuan’s Ideas Today

Most of this might seem abstract to you. The idea of an unfettered mind, one that isn’t chained to any single thought, event, or body part, offers a wide perspective. It allows you to not only have a mind more open to ideas, but also a mind that is more resilient to the challenges of life.

However, an unfettered mind isn’t a mind that moves along impulsive. An unfettered mind must first be trained. You have to chain it using focus practices, such as meditation, until you understand your patterns of thinking. Once you’ve become familiar and comfortable with your patterns, and worked to shape them like a swordsman would shape his technique, you can then unfetter your mind.

I know the contradictory nature of this idea can be confusing. The human mind is both the source for its problems and the solution to those problems.

So to translate Takuan’s ideas into something practical:

- Train your mind through focus practice.

- Learn to sit with your thoughts and watch their patterns.

- Work to change those patterns; train your mind.

- Allow your mind to move naturally according to your training.

- Watch your mind do this and then return to train it if it doesn’t move in helpful ways.

- Learn not to be attached to things. Death and loss are unavoidable; suffering, however, is avoidable.

It’s not easy to sit with thoughts. They can be uncomfortable, terrifying, loud, and violent. Yet, thoughts are just thoughts. You don’t have to act upon them. In fact, it is best not to act upon them at all. As you learn to listen to them, they naturally quiet. This too is the unfettered mind at work. If you let the mind settle, it will clear itself over time, just as muddy water will clear itself if left alone. But our habits stir that muddy water by ignoring the mind. It seems weird, but to stop the mind from stirring, you have to listen to it. Ignoring your mind is how you stir it.

The Unfettered Mind offers an interesting insight into samurai thought. While Takuan was a Zen monk, he wrote and taught samurai, so he was a part of samurai philosophy, what would later become known as Bushido. The collection of letters and essays is dense. You can still learn helpful ideas and find interesting quotes within it, but some of the essays become a tangle of Buddhist terminology and of Taoist ideas. Takuan often refers to the Way of Taoism, just as his friend Musashi did. The book is short, about 130 pages. If you are interested in samurai thought or Zen, give it a read. Takuan’s writings, of which The Unfettered Mind is just a small collection, has influenced Japanese thought since the 1600s. However, if you are just a casual anime watcher or a casual history book reader, I can’t recommend reading The Unfettered Mind. It requires an understanding of Buddhist thought to keep from becoming too confusing. But if you enjoy deeper, philosophical thinking, Takuan’s idea of an unfettered mind provides an interesting tangle that makes your reconsider how your mind works.

I think certain thoughts like “I feel hurt by your actions” need to be said to those who have done some harm, but yeah, after that, you can slowly detach and not look back for a while. The mind is like an internal prosecutor at times.