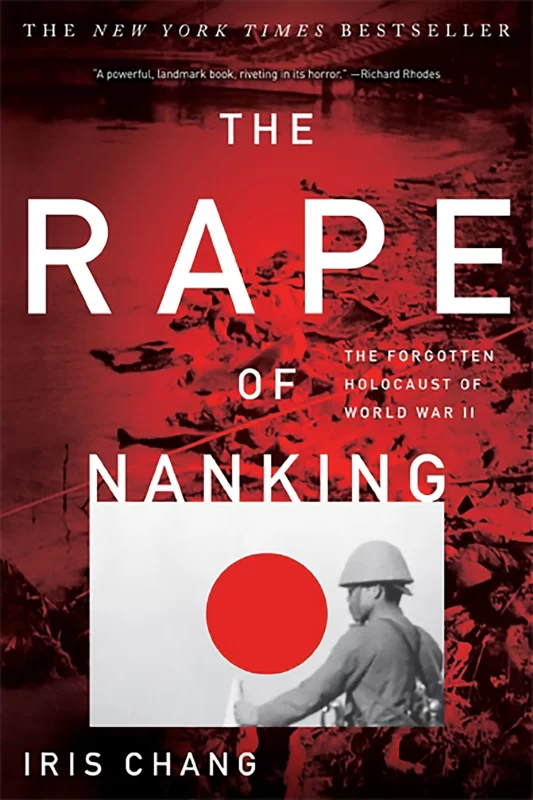

The Rape of Nanking covers the destruction of present-day Nanjing City by the Japanese during World War II. The book doesn’t hold back. In several chapters, I had to take a break from the relentless atrocities the author accounted.

The Rape of Nanking covers the destruction of present-day Nanjing City by the Japanese during World War II. The book doesn’t hold back. In several chapters, I had to take a break from the relentless atrocities the author accounted.

Nanking was the first area the Japanese went after taking Shanghai. The goal was to conquer China, and Japan has long had a desire to conquer China. Soon after becoming Shogun, Hideyoshi sent an invasion force into Korea with the goal of eventually taking China. The invasion failed. During World War II, Japan tried again, eventually occupying Manchuria.

The Rape of Nanking involved wholesale execution, torture, and rape of the populace. Japanese soldiers were trained to see the Chinese as less than human, as “pigs,” as they often called the Chinese. The Japanese soldiers would use Chinese men for bayonet practice, burn them alive, and hold beheading contests. The goal was to see who could behead the most in a period of time. As you can guess from the book’s title, women of all ages, including young girls, were raped. Chang wrote:

Chinese women were raped in all locations and at all hours. An estimated one-third of all rapes occurred during the day. Survivors even remember soldiers prying open the legs of victims to rape them in broad daylight, in the middle of the street, and in front of crowds of witnesses. No place was too sacred for rape. The Japanese attacked women in nunneries, churches, and Bible training schools. Seventeen soldiers raped one woman in succession in a seminary compound…

Old age was no concern to the Japanese. Matrons, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers endured repeated sexual assaults. A Japanese soldier who raped a woman of sixty was ordered to “clean the penis by her mouth.” When a woman of sixty-two protested to soldiers that she was too old for sex, they “rammed a stick up her instead.”

Chang goes on:

Little girls were raped so brutally that some could not walk for weeks afterward. Many required surgery; others died. Chinese witnesses saw Japanese rape girls under ten years of age in the streets and then slash them in half by sword. In some cases, the Japanese sliced open the vaginas of preteen girls in order to ravish them more effectively.

It was about here that I had to take a break from the chapter. Thankfully, she goes on to describe the efforts of Americans and Nazis and other foreigners to create a safety zone. She accounts how they saved women, men, and children from the madness by confronting the Japanese soldiers. They fended off raids by the Japanese against the safety zone and other trials. It is thanks to these foreign men and women that we know what happened. Most of Chang’s book pulls from their journals, photographs, and news reels. Yes, film of what happened exists and was smuggled out of Nanking. In fact, a copy of a news reel was even sent to Hitler, according to Chang’s research.

Whenever I read a book like this, whether it is about the Holocaust or the Rwanda genocide or events in Bosnia, I struggle. I struggle to believe such atrocities can happen. I struggle to understand how and why. The relentlessness of Chang’s account beggars belief. However, the destruction happened. The rapes happened. The murders happened. Chang touches on how in a section. Namely, the way the Japanese military was structured bred men who could rape and kill for fun. The training at the time was brutal. The brutality worked to empty the Japanese men of their humanity and to create a desire to get revenge for the abuse they endured. This doesn’t justify their actions, but it helps explain the psychology that led to atrocity. Dehumanizing the Chinese also helped them. Labels and language are powerful. They influence and reflect your view on the world. If the Chinese are less than pigs–after all, you can eat pigs–than it becomes easier to butcher them. The Japanese aren’t unique in this approach. Nazis dehumanized Jews, Gypsies, and their other victims. Likewise, colonial Americans dehumanized the Native Americans.

Dehumanization also combined with a feeling of exceptionalism. The combination of feeling superior to all others and the feeling of those others being a lower life form, allows people to do terrible things. Sometimes those terrible things don’t feel terrible, although Chang shares several accounts of Japanese soldiers who knew how they were being forced to lose their humanity. Yet, they also could do nothing about it.

The Rape of Nanking challenged me, as any book of its type does. I used to be able to read such books and watch bloody films without feeling troubled. However, as I age, I become more sensitive. Chang highlights an event that many have forgotten. Many history books merely mention it, focusing instead on what happened in Germany. Events in China were just as bad and deserve more coverage. Chang’s book reminds us of that.

Chang doesn’t go into it, but The Rape of Nanking shows the danger of dehumanizing people and having a misplaced sense of exceptionalism. The Internet and political discourse teems with these misconceptions. It’s dangerous. It takes little to push people over the edge and toward violence. We believe we can’t commit atrocities, but World War II revealed the banality of evil. It is a workaday event once certain thinking congeals. So even Internet dehumanizing can be dangerous.

So who should read The Rape of Nanking? History buffs, of course. But I also urge anyone who thinks Japan is “the best culture there is” to read it too. Chang did her homework well, as unbelievable as the World War II era can be. But be warned, it is a difficult, unrelenting read.

The author killed herself some time ago, perhaps because of the research surrounding the book.