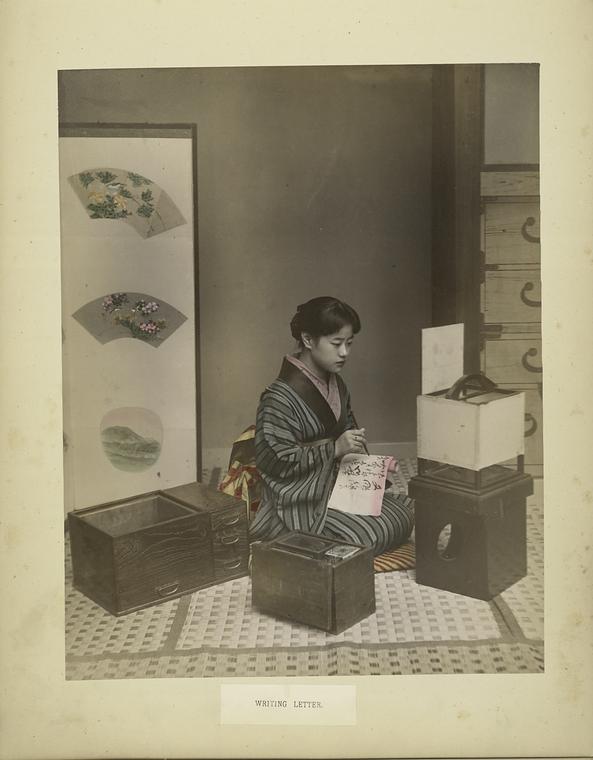

History tends to represent the voices of men and those in power. Typically, governmental officials, who are most often men, know how to read and write. And those documents are what survive. The majority of people in the past were illiterate and unable to write. Because of this, their voices disappeared outside of a few official references and moral documents the educated aimed at the public. Most of these lost voices belonged to women. Amy Stanley’s book Stranger in the Shogun’s City uses letters written to and from an educated woman named Tsuneno to reconstruct her life. While Tsuneno’s family belonged to the upper educated class–her family were True Land Buddhist priests–her letters offer a glimpse at what life was like in Edo just before Commodore Perry’s fateful visit.

Through the letters, Stanley pieces together Tsuneno’s personality and eventful life. She also manages to piece together the personalities of some of her brothers, particularly that of her older brother Giyu, whose careful writing and collecting preserved the chronicle of the family. Like most women, Tsuneno was married off early. In fact, she was married off at 12 years old, far younger than the norm of 14. Tsuneno’s stubbornness and sense of independence asserted itself within the first marriage, ending in her divorce and being sent back to her family. Tsuneno wanted nothing more than to live in the bustle of Edo. Eventually, she runs away with a priest whom she misjudges and winds up alone in Edo. The letters described her struggles and difficulties she caused her family. Although she was disowned several times, her brother Giyu never severed the connection they had.

Stanley peppers Tsuneno’s story with asides and other personal stories to provide context. Sometimes she zooms out to take the skyline view most historians take. Most of the time, she prefers to remain on the streets of Edo, describing the concerns of the people and the customs. Stanley doesn’t hesitate to speak about the silence she found between Tsuneno and Giyu’s letters. Sometimes, she can only speculate about the courses Tsuneno could take based on Tsuneno’s personality and the options women had at the time. Despite the difficult, Tsuneno manages to be her own woman, which caused her frequent marriage difficulties.

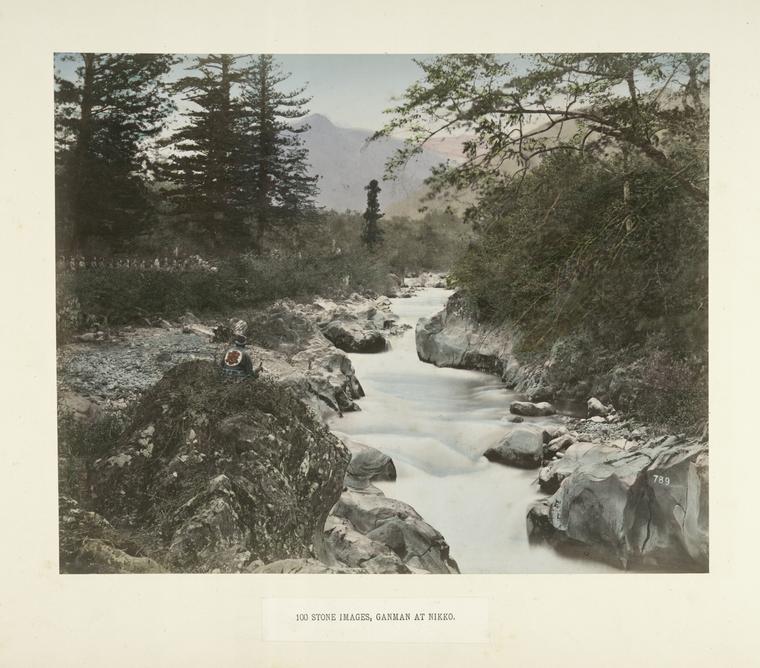

Stanley spends a lot of time discussing clothing and fashion. Apparently, this reflects Tsuneno’s concerns. She often lacked warm clothes or the fashion needed to succeed in a city where clothing or the lack marked your professional and social status. Stanley does a good job sketching the environment of Edo at the time, and the economic difficulties posed by the increase in migrants to the city. However, sometimes these sections feel a bit jarring compared to the sections focused on Tsuneno and her life. The sections outlining Commodore Perry suffer from this problem the most. Stanley provides interesting details about Perry that are often glossed over. Perry had 10 children and was looking forward to retirement, for example. Sometimes in Japanese history books, Perry feels a like a villain. Stanley’s sketch makes him feel human. But the section feels strange because of the shift. After all, at this point of the story, Tsuneno has died of illness, a common fate for people at the time. She didn’t live long enough to see the Meiji Restoration begin. Her life provides a glimpse at Edo just before it changed forever.

History books are often dry reads or so stuffed with facts you can’t remember them all. Stranger in the Shogun’s City reveals a singular life and a singular family without the trappings of legend or achievement. Tsuneno was a nobody. Her family served the Rinsenji temple, but many families served temples as priests. Yet, her letters and her brother’s journal entries provides a valuable perspective, a ground-level view. She doesn’t represent the peasant. She was well-educated. However, her fall from her family reveals how the lower classes struggled to make enough money to survive in Edo. In an era where women were limited in what they could do, she followed her calling, as difficult as it was. She paid her dues for it too.

Stranger in the Shogun’s City feels like reading a soap opera at times. Tsuneno’s life was that messy. But it is also a raw read. Stanley does what she can to represent everyone evenly. She explains the gaps in the correspondence and offers good context for those unfamiliar with the Edo period. Giyu’s frustration and love for his wayward sister remains constant throughout the book. As an eldest brother, I sympathized with Giyu; Tsuneno’s behavior often made me feel the same brotherly frustration.

I recommend you read Stranger in the Shogun’s City if you are interested in the lives in Japanese women and the Edo period. Stanley’s book helps fill the relative silence we have surrounding the lives of normal men and women within history. You will get a good feel for the personality of Tsuneno and her elder brother Giyu and their strained relationship.

Exploring the mid-1800s era Virginia City cemetery is notable as much for what it says as what it does not. Here and there, a stone monument stands in remembrance… five children of a family lost to influenza, an elderly husband and wife who died within weeks of each other. But there are also entire sections of the cemetery where there are no markers at all, their mere wooden remembrances long ago disintegrated into anonymity.

A few years back, I read, “The prison memoirs of a Japanese woman,” Kaneko Fumiko’s prison autobiography, “Nani ga watakushi o kō saseta ka” (What made me this way?), as translated by Jean Inglis. Some time, I’d like to read the Japanese version. It was very interesting to read something written by an intelligent (if perhaps somewhat naïve) woman of little means who lived during the social turbulence of Taishō period. There were better educated women writing at that time. But coming from families of greater means and influence, they didn’t necessarily communicate the lives of a typical woman in Japan. And if the stories do somehow leave a mark, even that implies something out of the ordinary. (Kaneko Fumiko was about to receive a death sentence.) Context is always important, so I think I get Amy Stanley’s excursions. The book sounds interesting.

The autobiography sounds interesting. It’s easy to forget how the historical record is one-sided: not only male but from the affluent class. Class differences often matter more than gender differences. After all, samurai women lived more restrictive lives than lower-class women, but we still know little about those lower-class lives. So too, samurai men had restrictive lives compared to male farmers in many ways. When the gaps in the lower-class historical record fill even a little, it’s cause to celebrate.