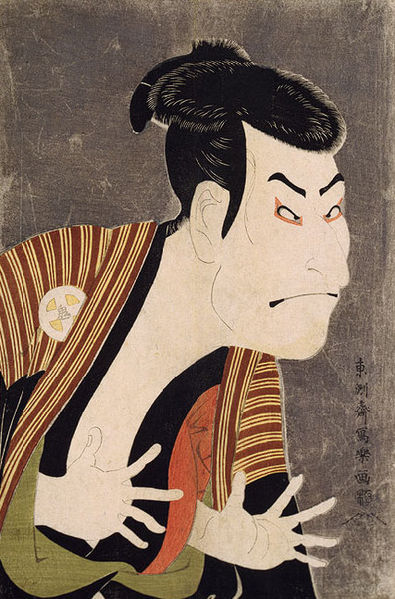

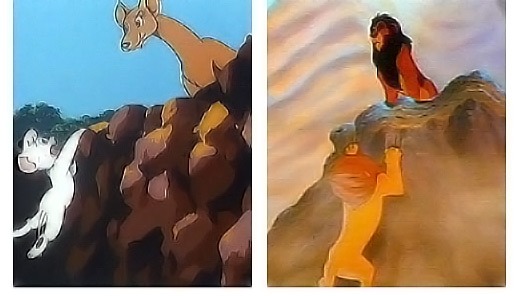

Osamu Tezuka is considered the godfather of manga. He popularized the format with his storytelling, using film techniques as a part of his approach. His art style mixes the style of early Disney with Japan’s native ukiyo-e style. This lends the impression that Tezuka’s work is “childish.” His three-volume story Ayako contradicts this perspective. As usual for essays like this, I will spoil this story.

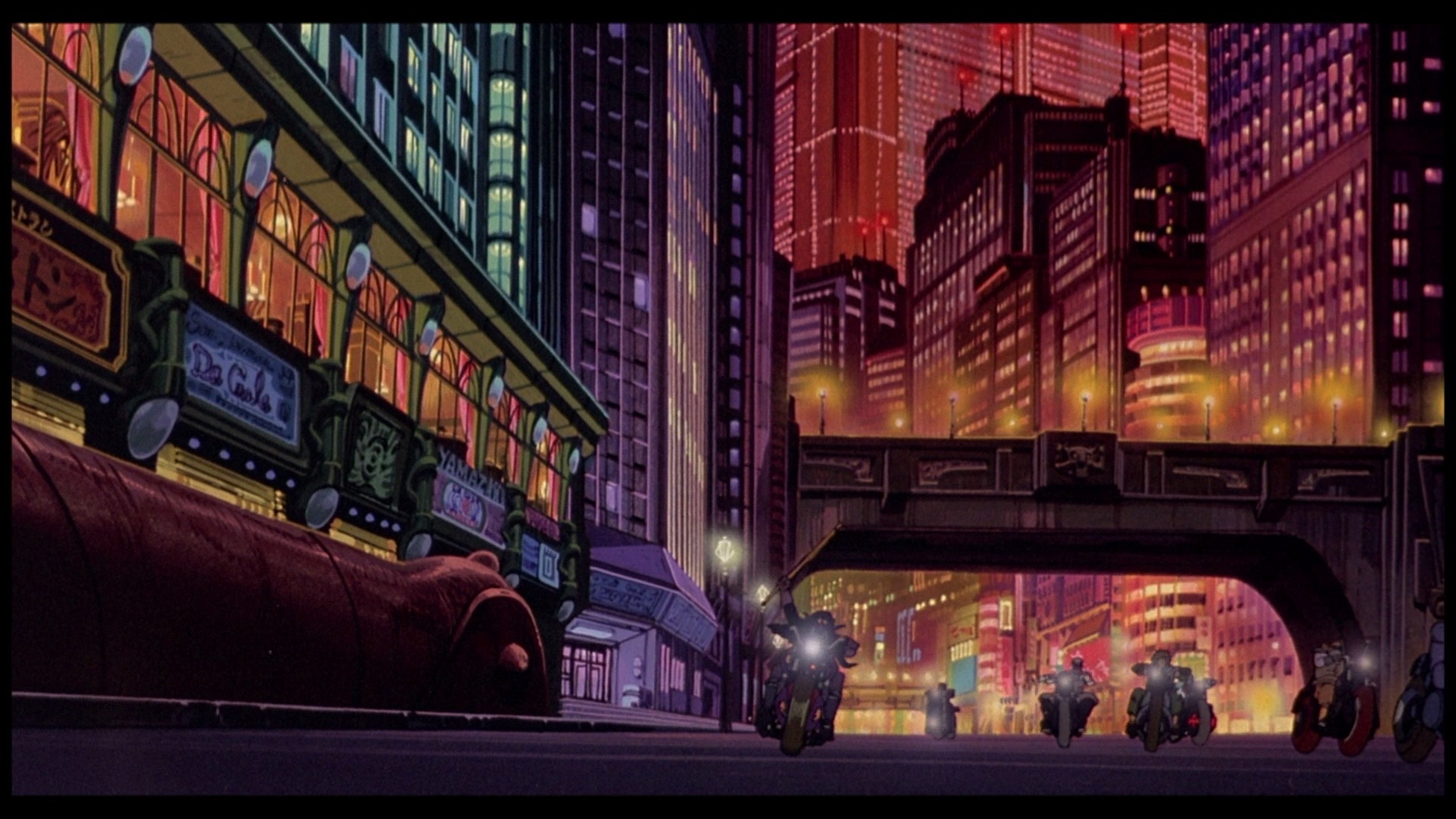

Ayako follows the tangled affairs of the Tenge, a Japanese landowning family, during the post-World War II period. The story stretches through the early 1970s. The volumes were published as a series between 1972 and 1973. Ayako centers around the family’s incest, violence, and exploitation as they try to navigate land ownership reforms, Japan’s Red Scare, the Korean War, and other geopolitical and social turmoil. Tezuka incorporates many different historical events into the story, such as the Shimoyama incident, an event where the first president of Japanese National Railways disappears. His body reappears the next day on a railway line. During this period, Japan and America suffered from Red Scares, a phrase which references growing fears about the spread of Communism and the beginnings of the Cold War. Japan and the United States saw the appearance of Communist political movements, and both governments moved to root out and shut down these movements.

The story begins with an inheritance squabble among the elder sons as the patriarch, Sakuemon, begins to fade in his old age. Jiro, one of these elder sons, has returned from the war and now works as an agent for the American occupation. Sakuemon had already promised to give his title as the head of the family to Ichiro on one condition: that Ichiro married a woman named Su’e and to make her become Sakuemon’s mistress. This affair leads to Su’e giving birth to Ayako, the story’s namesake character. To compound the situation, Jiro and Ichiro’s sister, Naoko secretly joins a socialist movement, and the youngest son, Shiro, is too intelligent for his own good. Shiro soon learns about Ayako’s true parentage, his father’s arrangement with Ichiro, and all the other garbage the family tries to keep quiet.

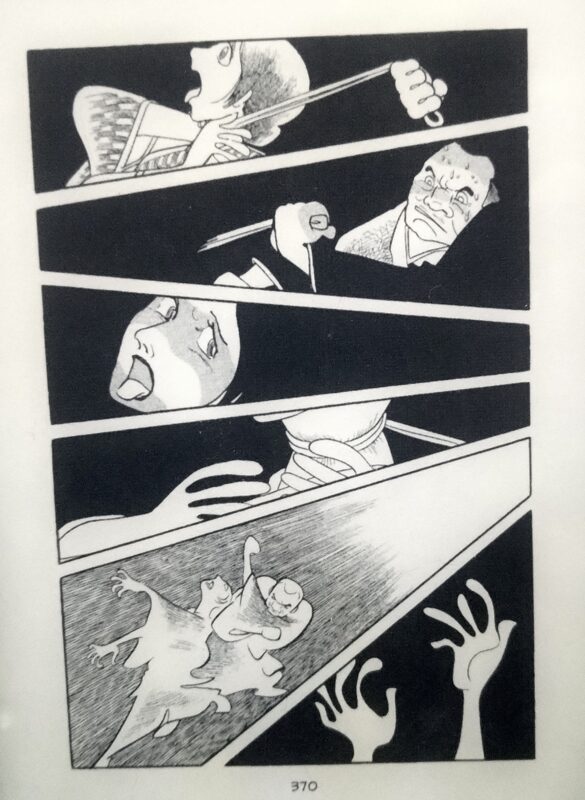

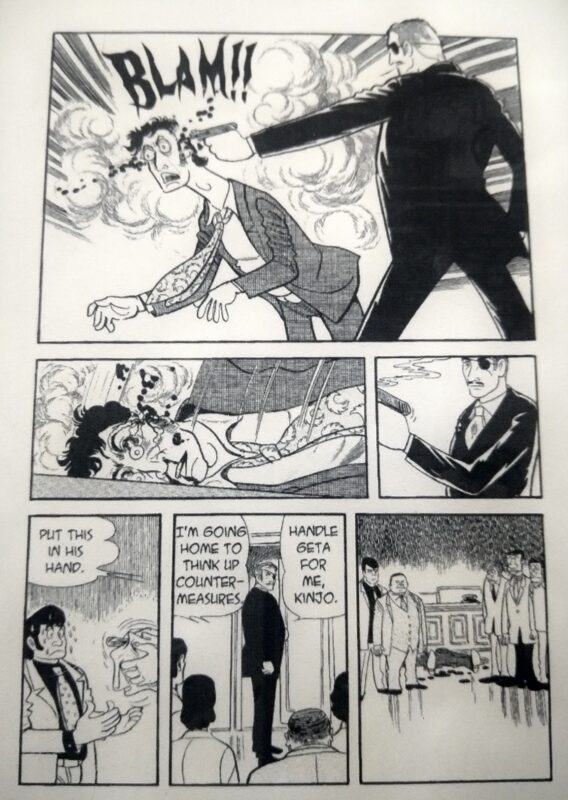

Soon after returning home and being treated as an outcast for failing to die honorably during the war, Jiro receives orders to assist in what comes to be known as the Shimoyama incident. Jiro’s job is to place the body of the president on the train line and to lead the president to his demise. To complicate things, Jiro’s target happens to be Naoko’s lover. As he hauls the body, Jiro gets blood on his shirt which the 4-year-old Ayako and the family’s intellectually disabled servant O-Ryo, who is hinted to be another product of the family’s incestuous habits. To cover his tracks, Jiro drowns O-Ryo, which Ayako also witnesses. Jiro claims to have been having a sexual affair with the maid and killed her to avoid disgracing the family if the affair would’ve been discovered. In order to avoid the family’s loss of face should Jiro’s murder of O-Ryo become public, Ichiro and Sakuemon decide to keep Ayako locked in a storehouse for the rest of her life. Why not just kill her? Sakuemon is fond of his daughter. Years pass with Ayako remaining unaware that her “big sister” Su’e is actually her mother. As the years pass, Shiro continues to watch the affairs of the family, becoming a “garbage dump,” as he calls himself, for everything the family wants to keep secret. Jiro is eventually forced to leave the family as police investigators get too close to his involvement in the Shimoyama incident, O-Ryo’s death, and other jobs he does for the American government. Jiro becomes a mafia boss and a killer as time passes.

Sakuemon has a stroke which locks him into his body. But before this event, he write his living will and tells his wife (Jiro, Ichiro, Shiro, and Naoko’s mother) not to reveal this will until Ayako becomes 15.

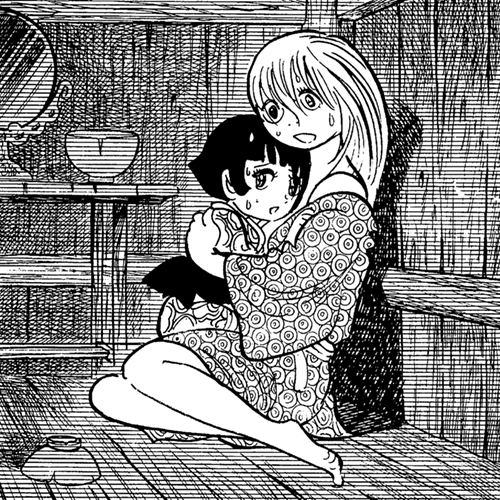

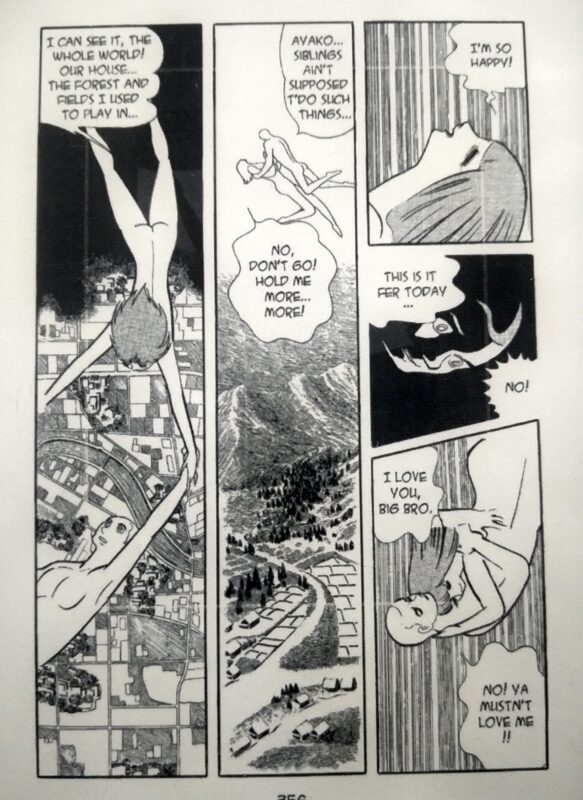

As Ayako matures into a young woman, her brother Shiro becomes her only male companion. He tells Ayako that Su’e is her mother. Fifteen-year-old Ayako convinces Shiro to love her and have sex with her. Her social isolation had grown so deep. Shiro, at first, resists her advances and tries to explain why incest is wrong, but Ayako’s desperation and the fact his status as the Tenge’s family’s “garbage dump” had eroded his sense of virtue, makes him give in. And so Ayako and Shiro develop a sexual relationship. Their relationship comes out, but like so many other scandals, the family hides it. When Ayako hits 15 years old, “Ma” reads Sakuemon’s will, which leaves 80% of his wealth to Su’e. When Su’e presents Ichiro with divorce papers and tells him she will take Ayako and the money and leave, Ichiro kills her. Because Su’e was still his wife, the inheritance transfers to him on her death. Unlike Jiro, Ichiro isn’t a killer, and so his actions haunt him for the rest of the story. Shiro quietly discovers this and the location of Su’e’s body.

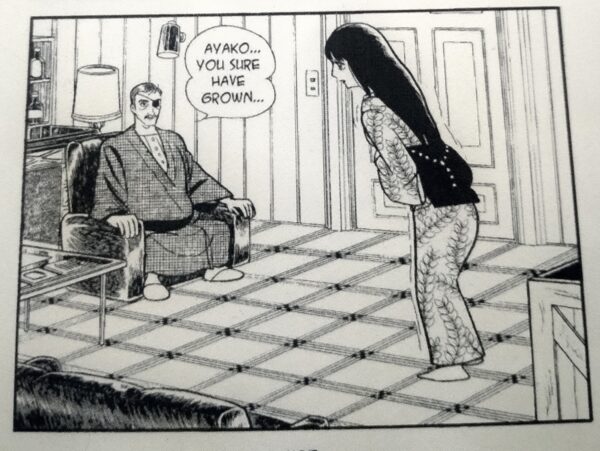

Government agents appear one day, wanting to purchase a few parcels of land from the Tenge for infrastructural development. Both parcels, however, are sensitive. The first one is the storehouse where Ayako lives; the second has a cesspit where Ichiro had dumped Su’e’s remains. Unknown to Ichiro, Shiro had encountered Su’e’s body a long time ago, and after deducing what had happened, he buried her remains in the nearby mountains. Ichiro refuses the purchase offers and mounts a resistance when the government agents enact eminent domain, bringing bulldozers and other equipment. Shiro manages to convince the agents to wait long enough for them to smuggle Ayako from the storehouse before the agents order it leveled. This event marks the beginning of the finale. Freed from the storehouse, yet still afraid of open areas, Ayako hides in a crate. For years, Jiro had been sending money to “Ma” for Ayako. Jiro had taken the name Tomo Yutenji to start anew. Using an address on one of these envelops, Ayako slips into a truck to find her benefactor. Despite remaking himself into a mafia boss who has many connections with top politicians, Jiro’s past begins to catch up to him. The lead investigator of O-Ryo’s murder had passed the case to his protege Inspector Geta. Geta investigates Jiro’s relationship with various politicians and connects his case with his mentor’s unsolved case. Jiro’s past as an American spy also closes in on him. The key player behind the events of 20 years ago now aims to clean up all the lose ends. Ayako appears in a crate just as this tangle begins to close around Jiro’s throat. Jiro attempts to hide his identity from Ayako and does what he can to rehabilitate her. Ayako has no idea of how to function as an adult; she even throws herself at Jiro as she had with Shiro years before, thinking that sex was the proper way to express love. Jiro refuses her, which Shiro had failed to do. Rejected, Ayako leaves the house where she encounters Inspector Geta’s son Hanao Geta. They talk for a time about Ayako’s problems, and Ayako throws herself at him. They make out, and Hanao becomes smitten. Ayako slips out to visit Hanao, and when Jiro learns of this relationship, he gives them a house to live together within but with the condition that Hanao recognize Jiro as Ayako’s guardian. Jiro also gives Hanao a deadline. If Hanao makes Ayako unhappy Jiro promises to “get him.”

This arrangement ties Jiro to Hanao’s father. While they rode from the house, they are targeted by a drive-by shooting. Jiro is hit several times while Inspector Geta gets hit in the arm. Jiro survives and traces the failed hit to his old American-employed handler who now happens to be his right-hand man. Jiro ends up inadvertently killing him while trying to get answers, and with both Geta now onto him, he flees back home. After encountering Naoko in the cemetery, who stabs him in the neck after he confesses to being involved in the train incident that ended with her lover’s death, Ichiro and the rest of the Tenge shelter him in the mountains. Ayako and Shiro encounter each other and Shiro takes her to convince Jiro to give himself up to Hanao. They find Jiro sheltering in a cave with Ichiro and the family doctor (another relative) who had been involved in the family mess from the beginning. Shiro confronts all of them in an effort to convince them to apologize for how they’ve treated Ayako. When no one does and tries to keep covering their sins as they always had, Shiro lights a stick of dynamite. It explodes and traps the entire family in a cave-in. Shiro is buried in the debris and dies. Ichiro’s guilt about murdering Su’e had troubled him for years, and now after Shiro spills all the family’s tea, this guilt plunges him into madness. Madness engulfs all of the Tenge, except Ayako and Hanao.

When they are found about 10 days later by Inspector Geta, Ayako and Hanao remain alive. Hanao dies soon after he is found. Ayako, for her part disappears as soon as she recovers.

Hanao Geta Senior is a re-occurring actor among Tezuka’s various stories. Tezuka treated his characters as actors, giving them various roles across his stories. Senior Geta appears in Astro Boy and other titles.

Tezuka’s Social Commentary

Ayako captures Tezuka’s social commentary. All of the main cast have a dark, twisted side. The story shows how the war and the American occupation damaged the traditional rural system and ruined many landowning families. Tezuka touches on land reforms crack open the already rotten Tenge family. You can view the Tenge family as an analog for Japan’s traditional family system. It had become incestuous, exploitative, secretive, and self-serving. The system had become too fragile to endure, cracking like a rotten thin-shelled egg. Ayako represents Japan itself. She is forced into isolation just as Japan was isolated from the world during the Tokugawa shogunate. Her protectors, including her brothers Shiro and Jiro, shelter her to the point where her understanding of morality and love becomes distorted. Shiro can be seen as an allegory for the pre-war Meiji period. Shiro remains traditional in his perspective even as he looks forward. He wants to keep Ayako as she is for himself. The Meiji reforms appear to be for the benefit of Japan, but many saw them as exploitative. Shiro’s incestuous relationship with Ayako represents this protective exploitation which lays the groundwork for Ayako’s sexually open relationships (representing Japan’s own too-openness to Western ideas). This too-openness is shown as a problem; whereas, an appropriate level of openness would be laudable. When bulldozers and other equipment knocks down Ayako’s storehouse, she is freed from the Meiji period’s cloister. This could be understood as World War II destroying the nationalism the Meiji period had built around “Japan,” trapping her with only a single window for sunlight.

Jiro, on the other hand, can be seen as a representation for the bitter, capitalist post-war period. He too wants Ayako for himself but he also aims to force her out of her old ways and become a “respectable modern (read: Western) woman.” In other words, Japan ought to convert to a respectable, Westernized nation, but one that is harmless and subservient to the protective powers that be (read: the American-aligned Japanese government). Jiro’s bloody past represents both Japan’s bloody war years and the American cynicism toward Japan. Finally, young Hanao Geta could be seen as a healthy society which wants Japan to be herself and choose her own way in her own time. Jiro’s status as a mafia boss points toward the Japanese government’s post-war corruption; indeed, Jiro buys off many politicians. But his continued entanglement with his past as a US spy represents how no matter how rich Japan may become, they cannot escape the reality of their past entanglement and its lingering influence.

The ending reveals Tezuka’s perspective on these allegories. Only Ayako, Japan herself, survives the darkness. She emerges and then disappears to live on her own, a part of the modern world and yet not. Ayako shows how life continues on no matter how poor the situation. As with any literary allegory, you can see these characters and events in other ways. Tezuka links the story to the American occupation of Japan early in the story and continues to provide touchstones with mentions of the Korean War and other events. You can also interpret Ayako as the archetypal woman who represents the suffering of women in history, as the trapped and eroding condition of the Japanese people, or as an allegory for how war and its aftermath debases life. Or you can view her as all of these at once. Literature allows for this depth of understanding and meaning.

Violence and Art

Ayako sits among Tezuka’s darker works. Beyond all the murders, the story shows men beating women, an attempted rape, and other violence. At times, the artwork breaks down in curious ways, such as this scene where Jiro’s legs become far too short.

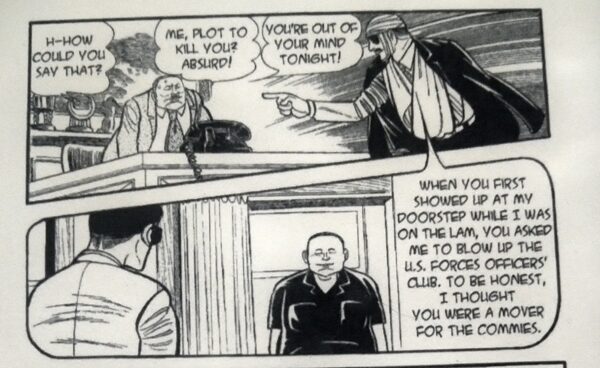

But Tezuka also plays around with interesting frame design like using this speaking bubble to act as a flashback frame.

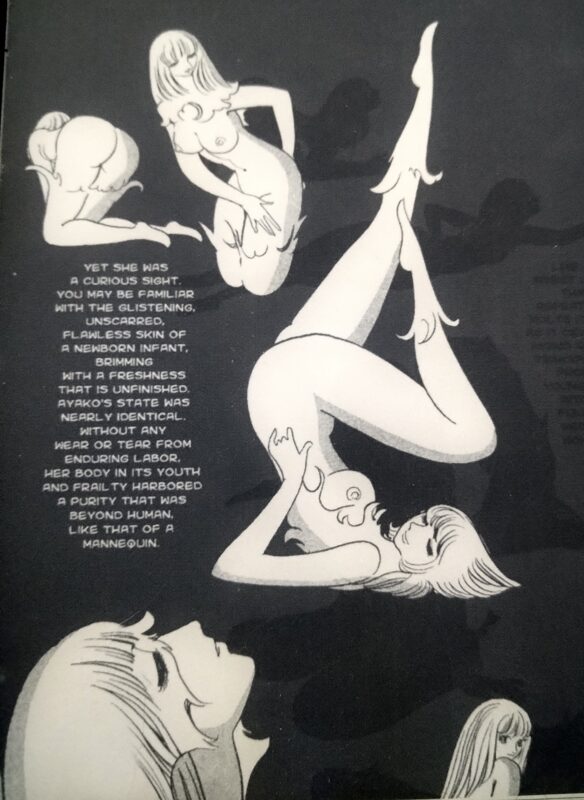

Tezuka’s character designs lend themselves well to aging. Naoko grows from a thin young woman to a chubby, aging housewife over the course of the story. All the characters age over the decades the story covers, some more than others with Ayako receiving the most careful aging treatment.

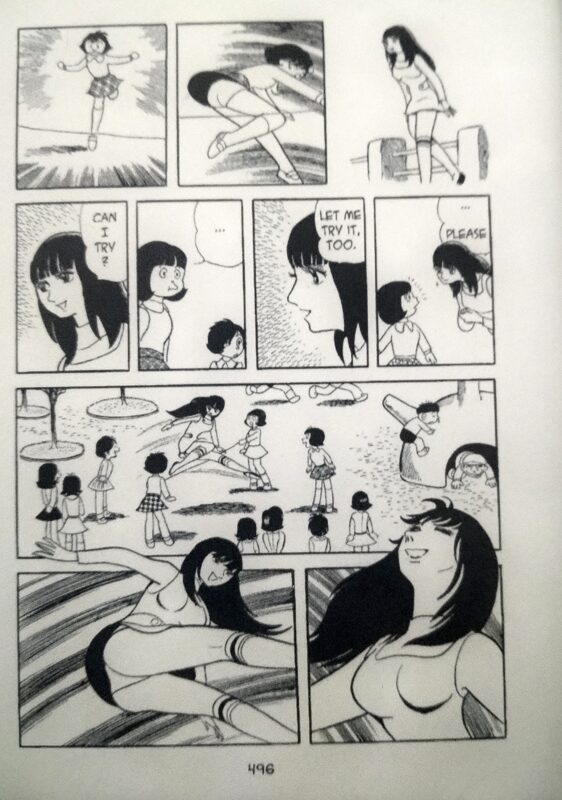

Readers witness Ayako at 4 years old, growing up through her first menstruation, and toward a young adult woman. Tezuka uses her nudity to represent her innocence, sensuality, and mental awakening to the reality she finds herself within. This panel shows her shedding her skin like a snake and like a cicada sheds its carapace. The panel is clever with how it shows her emerging into womanhood (and representing Japan’s emergence into modern nationhood). The panel also represents how life will continue to find agency and grow no matter its fate.

Ayako contains a few panels of what some may consider panty fan-service, where Ayako plays on a playground for the first time as an adult. The panels are drawn from a perspective where her underwear can be seen. This happens after the reader has already witnessed Ayako’s nudity and sexual awakening. To consider these panels panty fan-service is a misunderstanding of the aims of this scene; rather, it’s a show of innocence and joy. Ayako is able to touch on a childhood she missed. This “fan-service” acts as a touching and sad moment of characterization for Ayako before the story plunges toward its dark finale.

Ayako and Shiro’s incestuous relationship could be singled out as encouragement for the brother-love and sister-love themes we see in many romantic stories. Many modern takes on this theme features one character, usually the sister, who doesn’t see the relationship as a true problem, just as Ayako doesn’t. Few modern characters see this relationship to its conclusion as Shiro and Ayako do. But many modern stories also don’t aim at the allegories and social commentary as Ayako does.

Ayako weaves many different elements together to create a historical drama with depth and interesting characters. Only Ayako is innocent among the characters, a victim of her family and of wider geopolitical events which drives them deeper into their corruption. All the characters wish to use her for their own purposes, with the exception of poor O-Ryo and Su’e. O-Ryo proves to be an interesting character in her own way; she’s not intelligent and knows it, but she still wants the best life she can lead and cares for her charge, Ayako, as a mother would. Su’e is unable to truly act as a mother because of who Ayako’s father is, living as Ayako’s elder sister instead. Tezuka weaves quite a tangled story. Ayako acts as proof that manga can achieve literary status (not that fans of manga need more proof of this) with its social commentary and symbols. Above all, it tells a tragic and engaging story.