When I worked as a librarian, I had the chance to come across many interesting old books. Hara-Kiri: Japanese Ritual Suicide is one such book. Dating to 1968, the 103-page read covers the development and history of hara-kiri, or seppuku, in Japanese culture. Seppuku, as it is formally called, was a type of suicide practiced by Japan’s warrior class. It varied across history, as Seward explains. At first, it was a way to avoid capture and the resulting dishonor and possible torture. It began with falling on your sword. This was also a fairly common practice in the West. Roman history, for example, shows many defeated generals falling on their swords after their army is destroyed.

This battlefield practice mixed with the older suicide-murder practice Japan imported from China. When a leader would die, all of the servants, wives, concubines, and even horses were buried with the deceased. Yes, sometimes alive. Later, Japanese warriors would sometimes practice this when their lord died. They would commit seppuku so they could show their loyalty and serve their lord in the afterlife.

In the Hogen Monogatari, dating to 1156, Minamoto Tametomo disemboweled himself after a defeat. This is thought to be the first recorded instance of seppuku. Ten years later, Minamoto Yorimasa was wounded and defeated in battle and fled to Byodoin Temple. He wrote a farewell poem, perhaps the first recorded instance of a death poem. Then he “fell” on his sword.

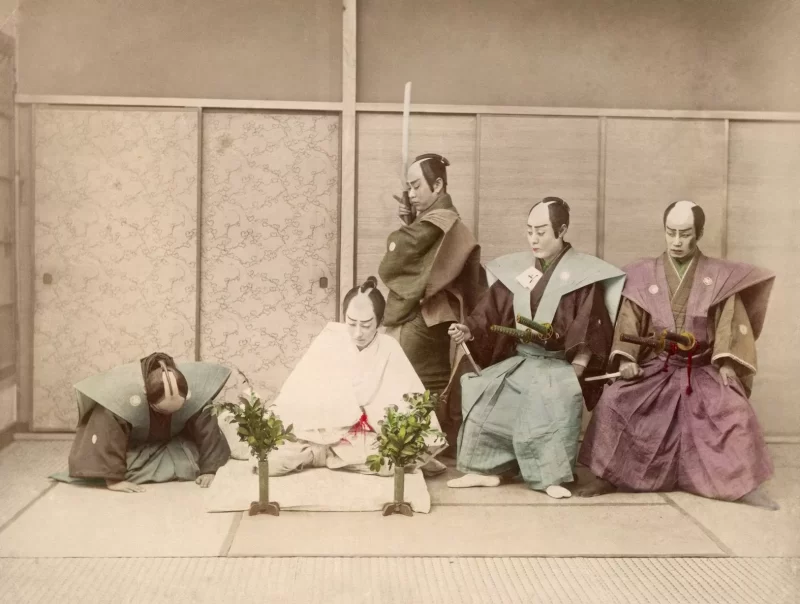

By the Edo period, this form of suicide became a precise, choreographed ritual. The first Westerner to witness it, Lord Redesdale (Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford), wrote about it in his book Tales of Old Japan. Seward includes the entire account. I will also include it:

As a corollary to the above elaborate statement of the ceremonies proper to be observed at the hara-kiri, I may here describe an instance of such an execution which I was sent officially to witness. The condemned man was Taki Zenzaburô, an officer of the Prince of Bizen, who gave the order to fire upon the foreign settlement at Hiogo in the month of February 1868,—an attack to which I have alluded in the preamble to the story of the Eta Maiden and the Hatamoto. Up to that time no foreigner had witnessed such an execution, which was rather looked upon as a traveller’s fable.

The ceremony, which was ordered by the Mikado himself, took place at 10.30 at night in the temple of Seifukuji, the headquarters of the Satsuma troops at Hiogo. A witness was sent from each of the foreign legations. We were seven foreigners in all.

We were conducted to the temple by officers of the Princes of Satsuma and Choshiu. Although the ceremony was to be conducted in the most private manner, the casual remarks which we overheard in the streets, and a crowd lining the principal entrance to the temple, showed that it was a matter of no little interest to the public. The courtyard of the temple presented a most picturesque sight; it was crowded with soldiers standing about in knots round large fires, which threw a dim flickering light over the heavy eaves and quaint gable-ends of the sacred buildings. We were shown into an inner room, where we were to wait until the preparation for the ceremony was completed: in the next room to us were the high Japanese officers. After a long interval, which seemed doubly long from the silence which prevailed, Itô Shunské, the provisional Governor of Hiogo, came and took down our names, and informed us that seven kenshi, sheriffs or witnesses, would attend on the part of the Japanese. He and another officer represented the Mikado; two captains of Satsuma’s infantry, and two of Choshiu’s, with a representative of the Prince of Bizen, the clan of the condemned man, completed the number, which was probably arranged in order to tally with that of the foreigners. Itô Shunské further inquired whether we wished to put any questions to the prisoner. We replied in the negative.

A further delay then ensued, after which we were invited to follow the Japanese witnesses into the hondo or main hall of the temple, where the ceremony was to be performed. It was an imposing scene. A large hall with a high roof supported by dark pillars of wood. From the ceiling hung a profusion of those huge gilt lamps and ornaments peculiar to Buddhist temples. In front of the high altar, where the floor, covered with beautiful white mats, is raised some three or four inches from the ground, was laid a rug of scarlet felt. Tall candles placed at regular intervals gave out a dim mysterious light, just sufficient to let all the proceedings be seen. The seven Japanese took their places on the left of the raised floor, the seven foreigners on the right. No other person was present.

After an interval of a few minutes of anxious suspense, Taki Zenzaburô, a stalwart man, thirty-two years of age, with a noble air, walked into the hall attired in his dress of ceremony, with the peculiar hempen-cloth wings which are worn on great occasions. He was accompanied by a kaishaku and three officers, who wore the jimbaori or war surcoat with gold-tissue facings. The word kaishaku, it should be observed, is one to which our word executioner is no equivalent term. The office is that of a gentleman: in many cases it is performed by a kinsman or friend of the condemned, and the relation between them is rather that of principal and second than that of victim and executioner. In this instance the kaishaku was a pupil of Taki Zenzaburô, and was selected by the friends of the latter from among their own number for his skill in swordsmanship.

With the kaishaku on his left hand, Taki Zenzaburô advanced slowly towards the Japanese witnesses, and the two bowed before them, then drawing near to the foreigners they saluted us in the same way, perhaps even with more deference: in each case the salutation was ceremoniously returned. Slowly, and with great dignity, the condemned man mounted on to the raised floor, prostrated himself before the high altar twice, and seated112 himself on the felt carpet with his back to the high altar, the kaishaku crouching on his left-hand side. One of the three attendant officers then came forward, bearing a stand of the kind used in temples for offerings, on which, wrapped in paper, lay the wakizashi, the short sword or dirk of the Japanese, nine inches and a half in length, with a point and an edge as sharp as a razor’s. This he handed, prostrating himself, to the condemned man, who received it reverently, raising it to his head with both hands, and placed it in front of himself.

After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburô, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of either in his face or manner, spoke as follows:—

“I, and I alone, unwarrantably gave the order to fire on the foreigners at Kôbé, and again as they tried to escape. For this crime I disembowel myself, and I beg you who are present to do me the honour of witnessing the act.”

Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle, and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku, who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body.

A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible.

The kaishaku, or second, was a trusted friend or vassal. What was once seen as an honorable way to die became an honorable way to be executed by the government. Seward goes into detail about how this shift happened and then goes into the fine details of the customs surrounding seppuku. He explains it all the way down to when the kaishaku can wear sandals and when he can’t. All the fine details were interesting in their precision and their variety based on the rank of the person who had to kill himself. Some of Seward’s descriptions of the actual suicides made me wince. Why the abdomen? In the culture of the time, it was considered to be the soul’s location in the body. Seward also explains this and how suicide methods varied among women and children. Yes, samurai children have been ordered to kill themselves.

Seward’s writing style is dated, but he remains readable. The book is also short, perhaps a two-hour read depending on how fast a reader you are. Here’s an example of Seward’s most-stuffy writing:

Thus, on one hand, there was the human feeling of abhorrence of blood and, on the other, the theoretical notion that seppuku exemplified the flower of Bushido or chivalry and should this be revered. (Seward is discussing the practice of killing oneself in a temple, not his own view of seppuku)

Hara-Kiri is worth a read if you are interested in samurai. Seward’s deep dive into the darker side of samurai culture troubled me at times as I imagined myself in the situation. I had to remind myself that seppuku was far rarer than we have the impression it was. Most samurai moved from lord to lord or even dropped their status as a samurai rather than kill themselves. Despite its age, Seward’s book remains valuable if you are interested in understanding this aspect of samurai culture.

I wish I could give you a reference, but I’m describing something that I saw a long time ago (20-years?) at a special display at the Osaka Museum of History. Two large scrolls were being displayed, each probably somewhat over one meter high by two-to-three meters wide. The first illustrated a battle between the forces of two feudal lords (possibly one was Sanada Yukimura). The second depicted the fates of samurai who were captured. Whatever horror you might imagine, it was probably illustrated on that second scroll.

The presenter explained that from a game-theory perspective, mercilessly torturing captives encouraged committed fighters. Those severely or mortally wounded and left on the battlefield would certainly have been beheaded (along with the dead) for trophies. [Having one’s head left on the battlefield was to be cursed… think “gashadokuro”.] Consequently, anyone captured would likely have been both relatively uninjured and either unable or unwilling to fight, possibly in flight.

Seppuku, or harakiri was consequently reserved for those of sufficiently high status to be afforded an alternative. Likewise, it might be offered when it was someone within one’s own forces who was accused of “dishonorable” conduct. It not only saved “face”, but the alternative would have been unimaginable, and may even have involved one’s family.

I’ve long wondered how much of those ancient accounts are old forms of propaganda. Not to say what the scroll depicts didn’t happen, but letters and diaries, scarce as they are, often illustrate a different view. Of course, views change across time. I’ve read many samurai writers who considered such violence and even seppuku as dishonorable. Better to live and make amends through service than die and be “worth nothing” to quote one English translation. Violence is a necessary evil meant for the final resort. But that branch of samurai writing was buried under what would inform how most view samurai now.

Thanks for sharing! It’s interesting, and if you come across a digital copy of that scroll, please send me a link!

Good point about propaganda. But there is a value to the game-theory of demonstrable reality in warfare, just as Cortez burning his own ships in front of the Aztecs guaranteed the commitment of their opponent in battle.

The scrolls had to do with the early history of Osaka Castle in the years after its construction on the site of the former temple-fortress of Hongan-ji. Given the new castle’s back-story, Tokugawa Ieyasu was notoriously unforgiving after its fall to his forces in 1615. He subsequently ordered the beheading of Toyotomi Hideyori’s 8-year old son, Toyotomi Kunimatsu, and effectively gave his combined forces of over 200,000 men permission to extract revenge upon the citizenry. Honor apparently wasn’t much of an issue in the aftermath.

Some quick looking, the first screen I described is the “Summer Battle at Osaka Castle”. It’s an 8-meter wide panel… larger than I recalled. I can’t find where the original is housed, though presumably in the Osaka Museum of History. The second panel I described was associated, possibly depicting the fates of surviving defenders?

Thank you for the additional info! Ieyasu and Kunimatsu’s relationship is a tragic and complicated one. There’s some evidence that if Kunimastu hadn’t had listened to the generals who was using him as a figurehead, Ieyasu may not have had him killed. And, sadly, you are right about the use of game theory in war. If only humanity would evolve out of our need deal violence on each other! But we need a few more tens of thousands of years to do that, I suppose.