Bushido Explained offers a good primer to how samurai thought across Japan’s different time periods. As the subtitle of the book states, it is a new interpretation for beginners. Bennett offers a broad, top view of samurai thought using diagrams and clear prose. While I wanted more details at times, Bennett sticks to offering a solid understanding of Bushido and debunking common misconceptions surrounding Bushido.

Namely, Bennett explains how Bushido wasn’t a unified philosophical system. Rather, Bushido was a hodgepodge of family rules, individual writers, localized warrior practices, and other ideas. Confucianism, Shinto, and Buddhism all gave different ideas to Bushido. This mix of ideas becomes apparent when Bennett summarizes various well-known samurai thinkers. Bushido can get complicated quite quickly, especially when you wade into the weeds. Some writers even go as far as describe how a warrior should stand and sit in various situations. The code of the samurai’s variety and impact on Japan’s history feeds back into the code, making it morph from practical lessons for war to the nationalism of World War II. Bushido Explained gives you a tour of the different environments without delving into the tangle. You can see this tangle when Bennett slows down to explain some of the power struggles within the ancient Imperial Court. That level of complexity defines Japan and, in turn, Bushido’s evolving ethical system.

Bennett stuffs history and Bushido into a scant 160 pages, with flow-charts breaking up the prose. At times, I felt like I was reading a blog more than a book with how frequent the prose was broken by the diagrams. I’m an old-school reader, so the constant breaks for pictures annoyed me. I started skipping over the diagrams in favor of reading the prose. Bennett explains the diagrams clearly in the text, but the constant breaks in the text also broke my focus. The diagrams serve their purpose, and I can see many people benefiting from them. But if you are a word-nerd, someone who wants to be sucked into walls of text, this book will break your focus if you don’t approach it more like reading a blog. But if you aren’t a deep-reader, this book’s design will work well for you.

Bennett helped me the most when he summarized the samurai writer’s perspectives within each time period. I’ve read most of them myself, such as Daidoji Yuzan or Yamaga Soko. Bennett’s summaries and organization helped provide the context I was missing when I read the books in isolation. I took notes as I read, jotting down many of the sections he quotes. I found the sections thought-provoking or valuable for my own quest for virtue. And yes, the samurai’s code has virtue at the heart of it. The parallels with Stoicism continue to surprise me.

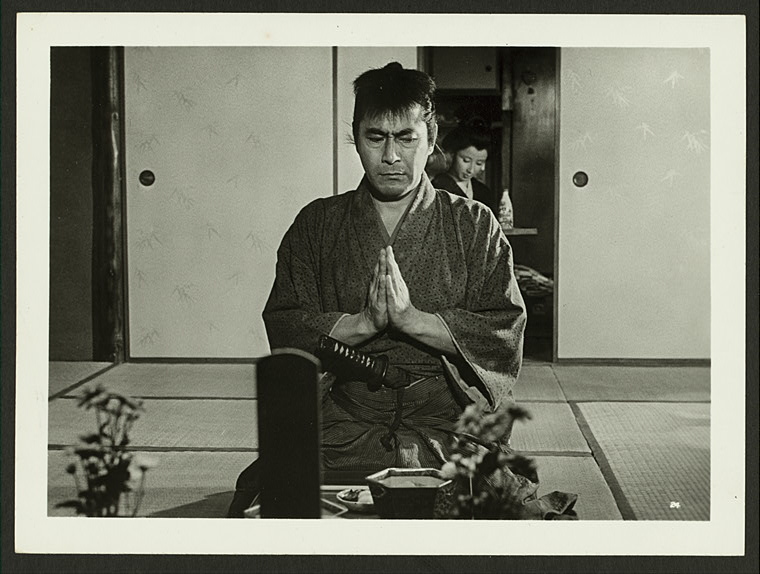

While Bennett does explain the importance of death for Bushido, he doesn’t spend at much time exploring it as I would’ve liked. But to be fair, you could write an entire book on just this idea. It forms the core of Japanese thought, and especially samurai thought. Of course, death also forms the center of Western thought in similar ways. Bushido Explained, as I had to remind myself, aims at being an overview for people who want to learn the gist of Bushido after being exposed to it in martial arts or through anime. Bennett has to know the topic inside and out to write such a succinct overview.

Bushido Explained would help an anime fan who doesn’t like to read, yet still wants to learn some of the reasons behind the tropes anime has. While Bennett doesn’t draw any anime connections in the book, focusing instead on a grand-view, it’s easy to see the connections between early samurai headhunting practices and shonen tropes of one-on-one challenges. My knitpicks as a in-depth reader becomes assets for those who don’t like to read. The book covers the range of samurai history and thought within 156 pages. I definitely recommend the book for those who don’t like to read or anyone who wants a fast overview of Bushido and samurai history.

However, as a deep reader, I’ve noticed a trend in books, which Bennett’s book falls into, of being cursory. It’s not a slight on Bennett’s work by any means. Rather, the reduction in book length and overall simplification of complex topics reflects our diminished attention spans. In new bestselling fiction, rapid point-of-view changes are common, for example. Across 2 pages in one book I attempted to read, there were 8 POV changes. While they were clearly marked out by paragraph breaks, it was too much of a mental whiplash for me. Bennett’s book, as I touched upon, broke my focus in a similar way with with the constant diagrams. All of this points to publishers catering to our cratered attention-spans, and this problem–at least, I see it as a problem–results from our screen-based consumption of content.

When I read, I don’t want a book to simulate a blog post. I want a deep-dive, a complete immersion into the minutia and tangle of a topic. But, when I worked as a librarian, I saw most people prefer shorter , entertaining works. This is fine. I’m just pleased people still read. However, I can’t help but wonder if our shortened attention spans, the the fact publishers have to cater to them, diminishes us. We can’t absorb complex ideas without deep focus, or so I’ve noticed with myself as my own focus diminishes. Whereas I could read for 4 or more hours in a block, I’m lucky to read without losing focus for an hour or two.

In any case, Bennett’s book is a good, if brief, read that I can easily recommend to readers and non-readers interested in samurai and Bushido. For anime fans, it is especially helpful. Most importantly, the book forced me to reflect on my own diminishing ability to focus and the trends in publishing that reinforces this diminishment. It makes me wonder what I need to do to reverse this trend within myself, or even if I can reverse it considering all the outside pressures that turn even books into blog-like media.

Skirting the topic of “Bushido” altogether, I’ll make a couple of observations about Bennett’s writing style-

As a technical reader, I’ll usually challenge myself at least once each year with something that requires several passes before I really understand the concept. These types of texts are often punctuated by diagrams or mathematics in a somewhat “academic journal” style, both as references and as a way to ground a concept. I’m wondering if Bennett intended the book to be referenced as an academic source?

Accordingly, you make an insightful observation regarding current writing styles. I’m presently churning out a short series of brief and easy-to-read posts summarizing events in 19th and early 20th-century China. The impetus was provided by a classroom full of graduate students who couldn’t glean enough information from a list of sources to construct a coherent argument for something they were supposedly passionate about. Rather disconcertingly, primary sources are rapidly becoming intellectually inaccessible to Americans due to declines in vocabulary and reading abilities. So I think publishers are increasingly looking for writings that parallel the informality and declining Flesch-Kincaid readability levels of presidential speeches.

It’s possible the book was intended as an academic source, but when I read it, I felt it was meant more for interested non-readers.

When I worked as a librarian, I encountered the very vocabulary and reading problem you describe. I had to “translate” ideas to simplified terms for many patrons, and these weren’t even primary sources. It’s a troubling development that doesn’t bode well. The gap between the learned and the unlearned, which doesn’t involve university degrees, is widening as you said. And all people have to do to be learned is read good, well-written and sourced books.

The point is there was no single “code/way of the warrior”, that’s romantic fabricated nonsense. People writing their own very varied philosophies over time isn’t it. The word Bushido wasn’t even in common use for centuries until that nonsense book I mentioned put out.

Misconceptions about muskets abound, they could hold a group on a man’s chest at 100 yards, bow wouldn’t. No, bows weren’t more effective since the period armor made them useless at distance but a musket went right through them.

Ah, sorry. I misunderstood. Yes, I agree that it wasn’t a single unified code for most of its history.

I remember reading how the samurai class were annoyed by ashigaru using muskets. Because ashigaru were often, exempting the richer land-holding ashigaru class, poorly armored, samurai would counter them using bows. But while anyone could learn how to fire a musket proficiently, bows took far too much training to be as proficient (which is what annoyed the writers).

Bushido is a romantic myth concocted at the end of the 19th century by Nitobe’s book “Bushido: The Soul of Japan”

Utterly romantic made-up nonsense that fabricated a mythos divorced from any knowledge of Samurai.

In a related myth, the real Samurai gave up swords as their primary weapons in the late 16th century and went to firearms, because they weren’t dumbasses. The swords were for ceremony and style after that.

Nitobe popularized and summarized the thoughts of a wide variety of writers. Bushido, until his work, was a regional and familial practice. I’ve read a variety of Bushido writings ranging from the 15th century up to the 1900s. Some where aimed at particular daimyo families. Other writers were more like Nitobe’s book, turning the “Way of the Warrior” into more specific practices. Here’s a short list of these books:

And many others. My library is full of Bushido writers. They sit beside my Greek and Roman philosophy books. Bushido is another system of philosophy that shares many characteristics with Stoicism.

You are partially correct that samurai used firearms, starting with Oda Nobunaga, but they didn’t fully abandoned the use of swords in battle either. The writings around the controversy firearms introduced during the Sengoku Jidai are interesting reads. Samurai used both. Bows, for the most part, remained more effective than early muskets. Effective armies used a combination of swords, spears, bows, and firearms.