It used to be anime was animation from Japan. That was why in the old, pre-Internet days it was often called Japanimation. It was known for being stiff, but super detailed and naturalistic compared to the more cartoony and exaggerated American animation. Animation was, after all, for children.

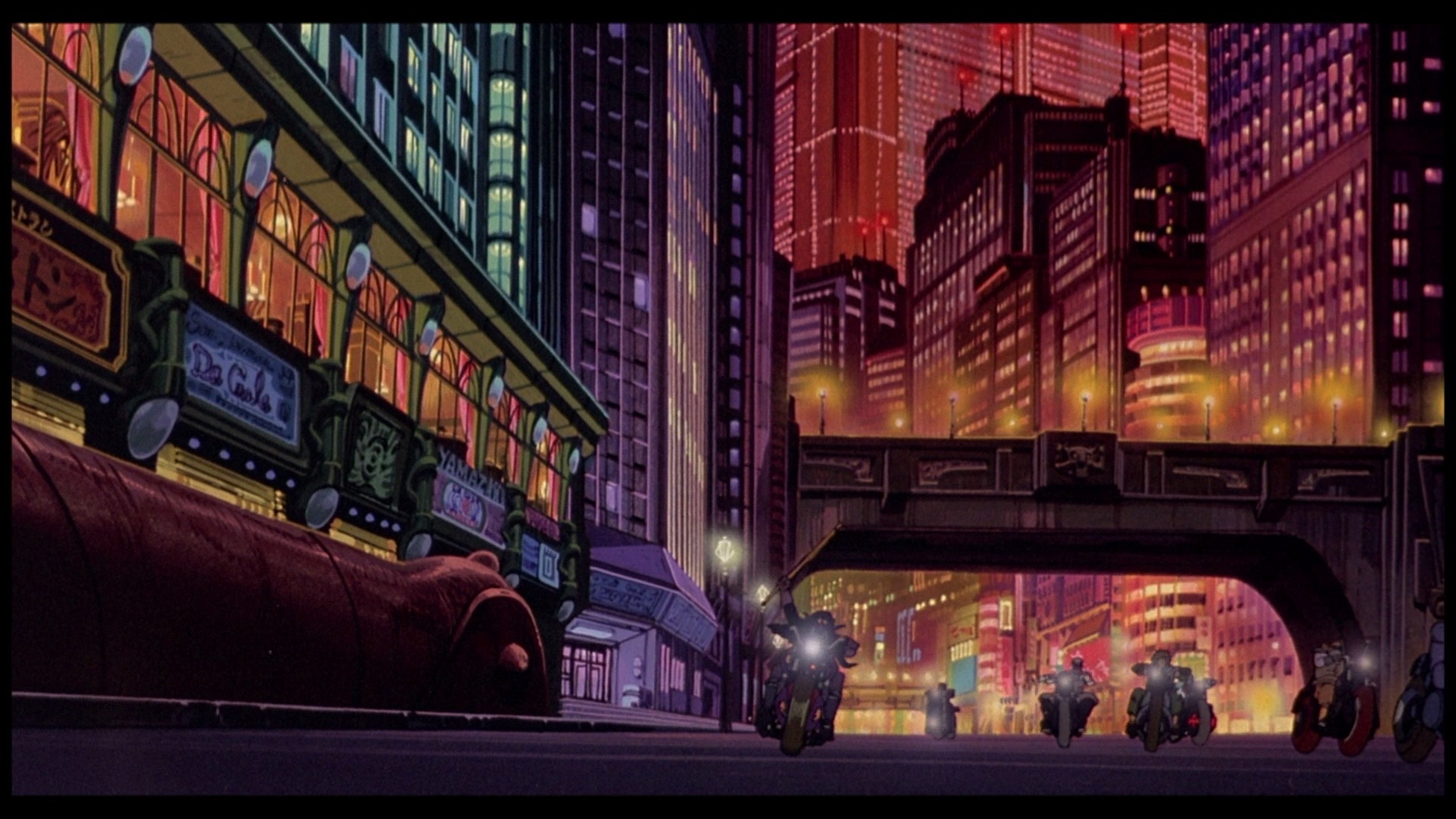

Then Akira and Ghost in the Shell happened. Those two films broke what many Americans considered what animation could do. Despite their success, Japanimation remained niche or for kids and teens until well into the 2000s. Fast forward to today. Anime is everywhere. You can find t-shirts with anime characters, figures, DVDs, and even anime-themed snacks at Wal-mart and other stores. I know anime fans of all ages (all the way up to 70+ years old). However, the mainstreaming of anime has raised the question: just what makes anime, anime?

In the past, you could say anime was animation that came from Japan, but that is not longer the case. Now you have anime like Castlevania, which is American, and The Daily Life of the Immortal King, which is Chinese. You could argue these series are anime-influences rather than anime. But when Japanese studios outsource their animation (Schilling, 2012) and Chinese studios outsource back to Japan (Schley, 2021), can you really call anime Japanese or a Chinese-produced anime Chinese? Where does the line between anime-influenced and real anime lay?

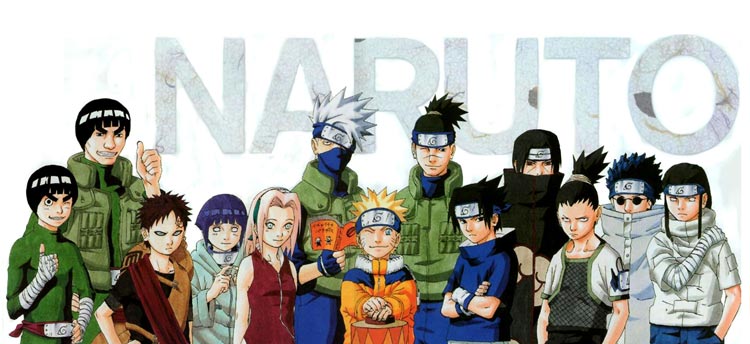

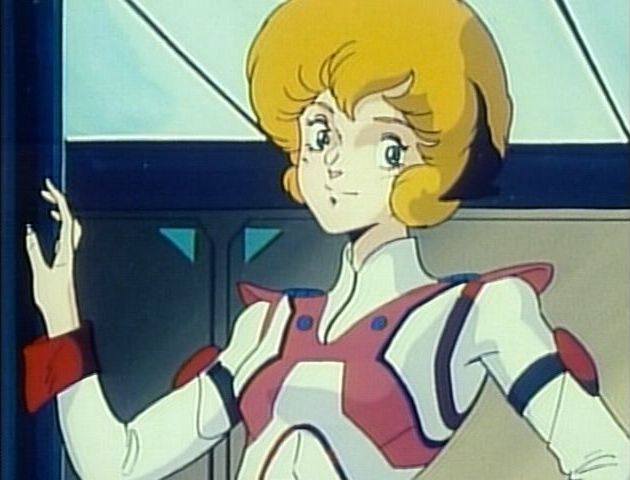

Anime developed from early Walt Disney animation techniques. Over time, it developed into the naturalism of the 1980s and 1990s until shifting back toward its earlier exaggeration we know now. Anime like Castlevania hearken back to the naturalist period. This makes it harder to pin down what visual style and stories make anime what it is. Not all anime is moe: big eyes, exaggerated hair, cute outfits. Many series sit between the exaggeration of moe and the naturalism of Robotech. Bleach provides a good example. Then you have anime that relies on its own art style, such as One Piece and Dragonball. You can’t point to a single series and say “This is what anime is” because such a statement will leave out something else. Likewise, you can’t say anime is Japanese or even call it Japanimation because of the cultural interchange and outsourcing of stories, animation work, directors, and more.

Rather, anime runs a gamut of visual styles and visual languages, but it does have some common factors:

Naturalism

Anime tends to be more naturalistic than most other animation styles. One Piece is an exception, and there are many others that have their own style. Generally, anime leans toward a more realistic depiction of bodies than American animation. But even this assessment isn’t entirely correct; GI-Joe and comic book cartoons are cases in point. However, they lack the simplification anime has. Anime anatomy tends to follow real, simplified anatomy and proportions from the neck down. Even when breasts are exaggerated, such feats are attainable with surgery and sometimes naturally. Compare this to American animations, which often feature more surreal body types and shapes, particularly with musculature. Of course, Jo-Jo’s Bizarre Adventure and Dragonball is more American in muscle design.

Expressive Eyes, Simplified Face

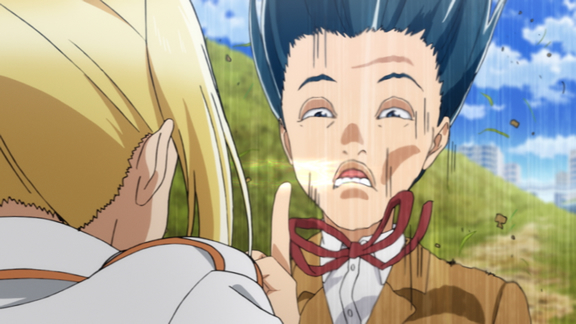

Anime likes expressive eyes. That’s why you often see large eyes on characters. The increase size allows animators more room to show emotions. Mouths and noses are secondary to the emotions of the eyes, even when eyes aren’t as exaggerated as in the moe style. Most of the time, noses and mouths are simplified to extremes.

Expressive Hair

Hair is a major character design trait in anime. You can often pick out a character based on hair style. For a long time, spikes defined anime, but you also see flowing hair, pompadours, and other wild designs. Because anime art tends to make the characters similar in facial features and (in the case of high-school) outfits, hair allows character designers to make unique-looking characters.

Cinematic Camera Angles

Anime has a long history of using dramatic and interesting camera angles. Many studios leverage the fact you don’t have physics to limit the perspectives you can show. I’ve seen camera angles from the inside of character’s mouths! Well-done anime leverages how camera angles can emphasize emotions, danger, terror, and other effects. Movies do the same, of course, but anime plays with this. You see POV shots, fly-ins, dramatic closeups, and 3D angles.

Emotional Visual Language

American cartoons exaggerate facial expressions using extreme distortion. Anime does this too, but most of the time, anime uses an established visual language to show emotions. Think sweat drops, spotlights, shiny eyes, and other visual phrases. Even more realistic anime, like Robotech and Castlevania use this visual language. It just isn’t as extreme as comedy anime show.

Environmental Story Telling

Environments suggest character emotions, back stories, and other details if you pay attention. This can be exaggerated by using anime’s visual language, to subtle, beautiful watercolor backgrounds. Contrast this to more static environments found in other animations, where the environment acts more as a stage than a character itself.

The Future of Anime

All of these elements can be found in live-action films. Anime, after all, models itself after film. American cartoons, not to beat up on them too much–I enjoy many of them, don’t aim to be cinematic experiences. Even regular television anime feature many cinematic elements: camera angles and dramatic close ups. If you want a good example of this, watch Violet Evergarden. It is one of the best anime in recent years.

While anime has a general art style, you can’t really use it as a defining factor of what makes anime what it is. Each time period of anime has a different dominating art style. Robotech doesn’t look like modern Gundam, for example. They have shared elements, such a expressive hair, despite the differences in visual style. Anime can’t be considered purely a Japanese medium because of the crossovers and outsourcing. Anime, for now, still retains mostly Japanese cultural elements, but as more Chinese, Korean, and American anime releases, the definition of anime will need to broaden. And this is for the better. Anime allows people to tell stories live-action often cannot (or at least not in a cost-effective way). As anime broadens, it will allow other cultures and histories, such as Korea and China, to tell their stories. I look forward to seeing new and different and, yes, non-Japanese anime releasing. The different takes on folklore and more will be interesting. Give me some Polynesian stories and legends. Give me Thai anime-horror.

Of course some purists won’t like the diversity anime is beginning to see, and, to be fair, has always seen. After all, Toei Animation handled many American cartoons, and Disney owned a Japanese animation studio until the early 2000s. The line between what is anime, as in the old Japanimation definition, and what isn’t has been blurred for many decades. Anime is mainstream now, so some of its unique features will fade as it becomes even more multicultural. I don’t want to see all of Japan’s influence in anime to disappear, and it won’t. Anime will remain Japanese just as Hollywood films will remain American. There’s plenty of room under anime’s umbrella for a variety of cultural perspectives.

References

Schilling, Mark (2012) Japanese companies outsourcing anime. Variety. https://variety.com/2012/digital/news/japanese-companies-outsourcing-anime-1118049388/

Schley, Matt (2021) Chinese Animation Projects Outsource to Japan. Otaku USA. https://otakuusamagazine.com/chinese-animation-projects-outsource-japan/