4Kids Entertainment. I’ll wait while you hug the porcelain and bring up your last meal.

4Kids Entertainment. I’ll wait while you hug the porcelain and bring up your last meal.

Feeling a little better?

Anime fans detest 4Kids for how they localized and censored and cut series like Pokemon, One Piece, Yu-Gi-Oh!, and others. However, the company is behind successful children’s shows that didn’t suffer the same fate: Cabbage Patch Kids and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Before we mark the company as a villain for anime, we have to consider the time period it committed its anime atrocities, as some fans see it. Hyperbole much? Saban Entertainment also gave Dragonball Z the same treatment during its US release (Daniels, 2008).

But at the time, anime wasn’t mainstream. Sure, it was around, but it wasn’t a part of the American childhood. Despite what anime fans say, 4Kids helped popularize anime. Al Kahn, the head of 4Kids, spent over 20 years distributing and promoting childhood stories. He saw kids playing Pocket Monsters on a business trip to Japan, and he convinced Nintendo and the owning companies to bring the game to the US. He also gave it its iconic name (Tsukayama, 2016):

He decided then that the game needed a cooler name than “Pocket Monsters.” “I didn’t like the name ‘Pocket Monsters,’” he said, partially because it didn’t sound different enough from other monster games. “I wanted the name to be more Japanese-y.”

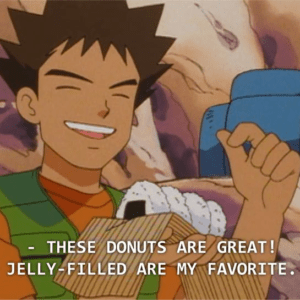

The statement is a little tone-deaf, and his Americanization of the anime proved controversial and uneven. He kept many of the Japanese names of Pokemon, like pikachu, but changed other aspects of the show. For example, he changed the name of the game’s protagonist from Satoshi to Ash Ketchum. The music and scripts were also rewritten to suit American children (Tsukayama, 2016). Japanese food was replaced with American foods because the company worried that American children wouldn’t recognize rice balls were food, leading to the (in)famous scene of Brock referring to rice balls as jelly donuts (Champers, 2012).

TV stations resisted the show, thinking it was too strange and too much like anime. Many shoved it into the 6am slot, a poorly performing time, but soon that slot was seeing more viewers than the prime after-school slots (Tsukayama, 2016).

TV stations resisted the show, thinking it was too strange and too much like anime. Many shoved it into the 6am slot, a poorly performing time, but soon that slot was seeing more viewers than the prime after-school slots (Tsukayama, 2016).

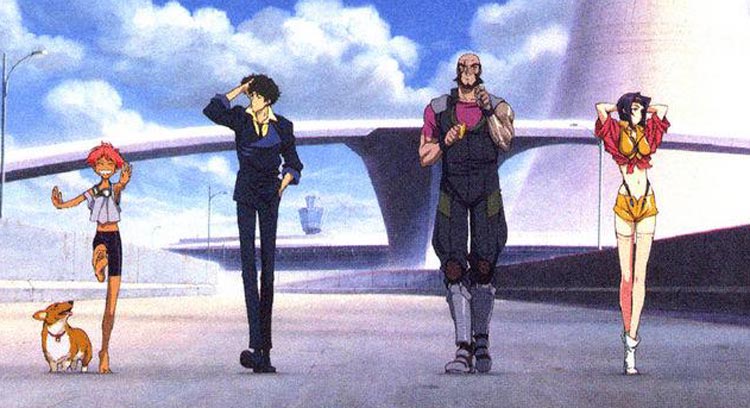

But 4Kids’ concerns may not have been too far off, considering the time. During the 1990s, anime was still hidden in a cultural niche despite Ghibli film releases. I’m not justifying what they did, but their localizations did introduce children to Japanese elements. It was a step toward wider acceptance of anime and Japanese culture. They ran into trouble when they tried the same tactics with One Piece in 2004. By this time, people had become used to anime’s Japanese elements, so when one of the most popular show about pirates hit the US, localization wasn’t necessary. But 4Kids wasn’t with the times.

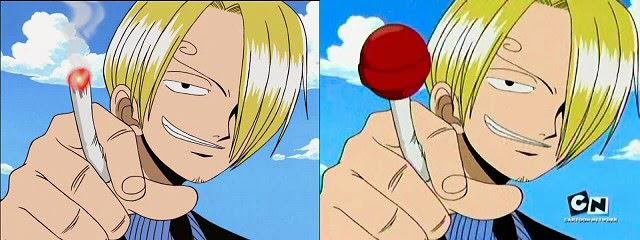

Instead, the company followed their habit and eliminated One Piece‘s Japanese and violent elements, never mind how violent American TV had become. 4Kids digitally changed all firearms to look like toys. Cigarettes became lollipops or poorly edited out, leaving smoke trails behind. They also cut a large number of episodes, including entire story arcs, and compressed multiples episodes into one.

As you can imagine, fans weren’t pleased.

Considering the US’s history of children’s shows, 4Kids’s decisions make sense. It was a few years after 9/11 and violence in media was under fire. Although TV continued to show ever-escalating levels of violence despite the outcry in some areas of the country. But 4Kids had fallen out of touch with its now-Japanese-culture savvy audience. Eventually the Japanese animation studio that created Yu-Gi-Oh!, 4Kid’s flagship earner–earning $152 million for the company between 2001 and 2009–claimed 4Kids owed it for making secret agreements with TV stations and home video companies and handling royalties in shady ways (Gardner, 2011).

A series of bankruptcies followed with the most recent happened in September 21, 2016. The company attempted to distance itself from its now tainted and infamous 4Kids brand by renaming itself 4Licensing Corporation on December 21, 2012 (4Licensing, n.d.; United States, 2012). But the damage was done with fans as the meme “What if 4Kids got show title” shows.

The Dangers of Localization

One Piece and Yu-Gi-Oh! suffered the most from 4Kid’s localization. Pokemon survived mostly intact with only jelly donut-level problems and a few cut episodes. 4Kids had a role in making anime more mainstream in the US, although the most avid 4Kids hater would deny that. However, the company failed to pay attention to their audience’s level of comfort and acceptance for Japanese elements as time passed. Their Pokemon and early Yu-Gi-Oh! localizations had cut a road for new anime fans who wanted the genuine experience. Also, by 2004, anime communities had sprung up online that had access to uncut episodes of One Piece and more.

The removal of Japanese elements and violence can compromise the vision and message the author intended. Violence in anime, for example, may be a comment on the human condition. Eliminating it removes that message. In One Piece’s case, removing cigarettes and making firearms look like toys, denies the danger and roughness of pirate culture. It hurts characterization.

Japanese culture references reveal part of the author’s identity and experiences. It gives context to the story, and without those references, the message of the story may garble. Not to mention it is insulting to substitute American elements for Japanese. It suggests American (or British, or French, or whatever culture is substituting for Japanese) is superior. It also insults the intelligence of the viewer. After all, even a child who had never seen a rice ball and know its food when characters eat it.

Japanese culture references reveal part of the author’s identity and experiences. It gives context to the story, and without those references, the message of the story may garble. Not to mention it is insulting to substitute American elements for Japanese. It suggests American (or British, or French, or whatever culture is substituting for Japanese) is superior. It also insults the intelligence of the viewer. After all, even a child who had never seen a rice ball and know its food when characters eat it.

Now some aspects of localization are necessary. Some idioms don’t translate well between cultures, and sometimes you run against language limits. Some languages have words others do not have have, so an approximation is needed. 4Kids helped American children wean into anime, but as exposure and understanding of Japanese culture became common, localization of the type the company practice wasn’t necessary.

Vilifying 4Kids

Segments of the anime community can’t forget what 4Kids did. Memes still circulate about the company’s handling. Anime fans are understandably sensitive to localization. They still have the dub vs. sub debate raging. However, even subtitled anime are localized. Localization can only be prevented by watching anime in Japanese and being immersed in Japanese culture. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to enjoy a story as close to the original as possible. However, dubs play an important role in making anime more accessible, which benefits the medium outside of Japan. 4Kids doesn’t fully deserve its smearing in the community. Yes, they handled their properties poorly, and they were….unsavory…..in their “Japanese-y” approach to Pokemon. Their method denigrated Japanese culture.

Segments of the anime community can’t forget what 4Kids did. Memes still circulate about the company’s handling. Anime fans are understandably sensitive to localization. They still have the dub vs. sub debate raging. However, even subtitled anime are localized. Localization can only be prevented by watching anime in Japanese and being immersed in Japanese culture. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to enjoy a story as close to the original as possible. However, dubs play an important role in making anime more accessible, which benefits the medium outside of Japan. 4Kids doesn’t fully deserve its smearing in the community. Yes, they handled their properties poorly, and they were….unsavory…..in their “Japanese-y” approach to Pokemon. Their method denigrated Japanese culture.

Despite all of this, 4Kids has an important place in American anime culture. They helped make anime mainstream to the point where Pokemon and Yu-Gi-Oh! weren’t considered anime. They were considered cartoons. This small distinction allowed anime to move from a niche and into the American childhood. It created several generations of anime fans that later moved toward other anime series, such as One Piece. No matter how much the anime community vilifies 4Kids, the company had an important role in the development of anime in the United States.

Reference

“4Licensing Corporation Files for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy | Business Wire”. www.businesswire.com. http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160922006380/en/4Licensing-Corporation-Files-Chapter-11-Bankruptcy

Ali, R. (2009). Yu-Gi-Oh! & Cabbage Patch Kids U.S. Parent 4Kids Entertainment for Sale. The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/08/04/AR2009080401638.html.

Chambers, S. (2012) Anime: From Following to Pop Culture Phenomenon. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications. 3 (2) 94-102.

Daniels, J. (2008) “Lost in Translation”: Anime, Moral Rights, and Market Failure. Boston University Law Review. 88 (709). 709-745.

“UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION: FORM 8-K: 4Licensing Corporation (December 21, 2012)”. Edgar Online. December 21, 2012. http://yahoo.brand.edgar-online.com/displayfilinginfo.aspx?FilingID=8990367-1208-18945&type=sect&dcn=0001140361-12-052927

Tsukayama, H. (2016) Meet the man who made Pokemon an international phenomenon. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2016/08/04/meet-the-man-who-made-pokemon-an-international-phenomenon/

German dubs didnt cut and destroy anime as much and anime still went popular hete.

Thanks for the input! Do you think Germany and the US would have had an equal acceptance of anime at the time?

4Kids helped introduce a generation or two of kids to Japanese anime, but the thing is, it’s up for speculation as to how much. There was a whole Japanese anime boom in the ’90s, and many companies wanted to cash in on that. Besides 4Kids, you had FUNimation, Saban, Ocean Group, and more trying to reap the rewards. Speaking of which, Saban didn’t edit Dragon Ball Z nearly as much as 4Kids would have, and we know exactly what they would have done thanks to Kai airing on 4KidsTV.

I feel there’s something more to this story that we’re not getting. Pre-“jelly donuts,” 4Kids still dubbed Pokémon with their typical quirks (removing kanji, CGI edits that look conspicuous now) but nothing that could be considered an extreme. One thing that isn’t mentioned is that part of the reason why Pokémon lent itself well to the 4Kids style is that from Hoenn to Sinnoh, the games were culturally neutral. Despite the regions being designed after Japanese islands, the actual locales had little that were distinctly Japanese about them.

Do you have any other sources that back up your assertion that Al Kahn gave Pokémon its name? Washington Post charges you to read that article you linked and all I can find with Google is that “Pokémon” was part of the localization process, using a contraction of POKEtto MONsutā. As far as I can tell, Al Kahn didn’t become involved with Pokémon until the anime, which came out well after the games were released.

I’m pretty sure that those uncut episodes of One Piece were really just the Japanese dub. Speaking of the anime, this article conventiently leaves out that 4Kids deliberately did a poor job of dubbing One Piece. Seriously, they wanted Tokyo Mew Mew (their second worst dub) and Ojamajo Doremi, but they received One Piece too as part of a package deal, and rather than just do nothing with it until their license on it expired (or until they could find a loophole or something that would allow them to give it to another company), they decided to sabotage it. They nearly killed One Piece in the West. Thank God FUNimation managed to get ahold of it. Additionally, the general consensus is that they didn’t have to edit/censor One Piece nearly as much as they did. In fact, when you consider what Dragon Ball Z managed to get away with, they didn’t have to edit/censor any of their shows nearly as much as they did.

Regarding Yu-Gi-Oh, even though they tried their best with it, they still managed to turn it into a different show. Thanks to them, not only is Yu-Gi-Oh is seen as a children’s card game in the West, but the only way to get a proper Barrel Dragon (among others) is to either get a fake/fan-made one, or import from Japan. In Japan, the card game is aimed at teenagers. Not to mention that for a time, the English version of the manga was butchered. For an example, Joey/Jonouchi calling out to Yugi in one panel, became him asking if he needs his insulin or something. Interestingly enough, this article omits the truly tragic part of 4Kids’s history. They went under as they were trying to undo their mistakes, though, for every step forward they took, they took at least two steps backward. A perfect example is the situation with the uncut dub of Yu-Gi-Oh. They worked with FUNimation to release an English dub of Yu-Gi-Oh that’s how the TV airing should of been. However, they did this (and many other things) behind TV Tokyo’s back, which resulted in a lawsuit(s). They never were able to get over their own greed in time.

Last of all, did you bother trying to contact the creators of Shaman King, Tokyo Mew Mew, and the other Japanese anime that 4Kids dubbed to see how they feel about the company’s censorship/edits? Kazuki Takahashi has spoken on the matter and he hates the censorship.

First, thanks for such a great, informational comment!

The Washington Post article also appears in various other Associated Press newspapers. Such as the Denver Post and Sydney Morning Herald.

The 90s certainly laid the groundwork for the access to anime we enjoy in the West today. Saban had as much clout as 4Kids did in the Saturday morning slots. However, I don’t recall watching Funimation shows (and I would’ve have!). This suggests they weren’t widely broadcasted.

4Kids certainly made money grabs which came around to finish them off as you stated. While Funimation didn’t censor or localize as much as 4Kids, it was still done more than it is today. Some of this was because the burst in interest was still new. Anime had been around for decades, but suddenly companies saw a market they apparently weren’t quite ready for. They had to chart the course rather than follow a map. 4Kids was likely worried about alienating parents.

I don’t know of any creator who enjoys watching their work mutilated.