Revolutionary Girl Utena is a game changer on the order of Evangelion. Like Sailor Moon, Utena is a magical girl story. The story is stuffed with symbolism and considered a post-modern fairy-tale (Haeker, n.d). This symbolism is what makes many people consider Utena the Evangelion of shojo (Rose, 2013). I will touch on some of these symbols later. Like other magical girl stories, Utena focuses upon the gender roles females have in society. Namely, it looks at how women can be independent of men (Brown, 2008). Utena, the heroine of the story, does not look to men for help. Rather, she embodies many of the same masculine characteristics. She is a character who ignores her expected gender role. Utena avoids the fate most Western female characters face. Many women in stories end up as obedient mates who wait for their princes to save them. These women transform from “bashful virgin to sexual object to doting wife and selfless mother” ( Bailey, 2012 citing Andrea Dworkin). Think about Disney princesses if this seems a little too academic. They wait around for their prince and are held up as something to possess. Utena says screw that.

Revolutionary Girl Utena is a game changer on the order of Evangelion. Like Sailor Moon, Utena is a magical girl story. The story is stuffed with symbolism and considered a post-modern fairy-tale (Haeker, n.d). This symbolism is what makes many people consider Utena the Evangelion of shojo (Rose, 2013). I will touch on some of these symbols later. Like other magical girl stories, Utena focuses upon the gender roles females have in society. Namely, it looks at how women can be independent of men (Brown, 2008). Utena, the heroine of the story, does not look to men for help. Rather, she embodies many of the same masculine characteristics. She is a character who ignores her expected gender role. Utena avoids the fate most Western female characters face. Many women in stories end up as obedient mates who wait for their princes to save them. These women transform from “bashful virgin to sexual object to doting wife and selfless mother” ( Bailey, 2012 citing Andrea Dworkin). Think about Disney princesses if this seems a little too academic. They wait around for their prince and are held up as something to possess. Utena says screw that.

Revolutionary Girl Utena also teaches a few other lessons. First, Utena faces challenges that come her way regardless of whether or not she wants to. When challenged, she gives her best effort. This points out how we often have to face things in life would would rather not have to. Utena also does this without hesitation or complaining. As I mentioned before, she doesn’t seek male help, but takes on these challenges herself.

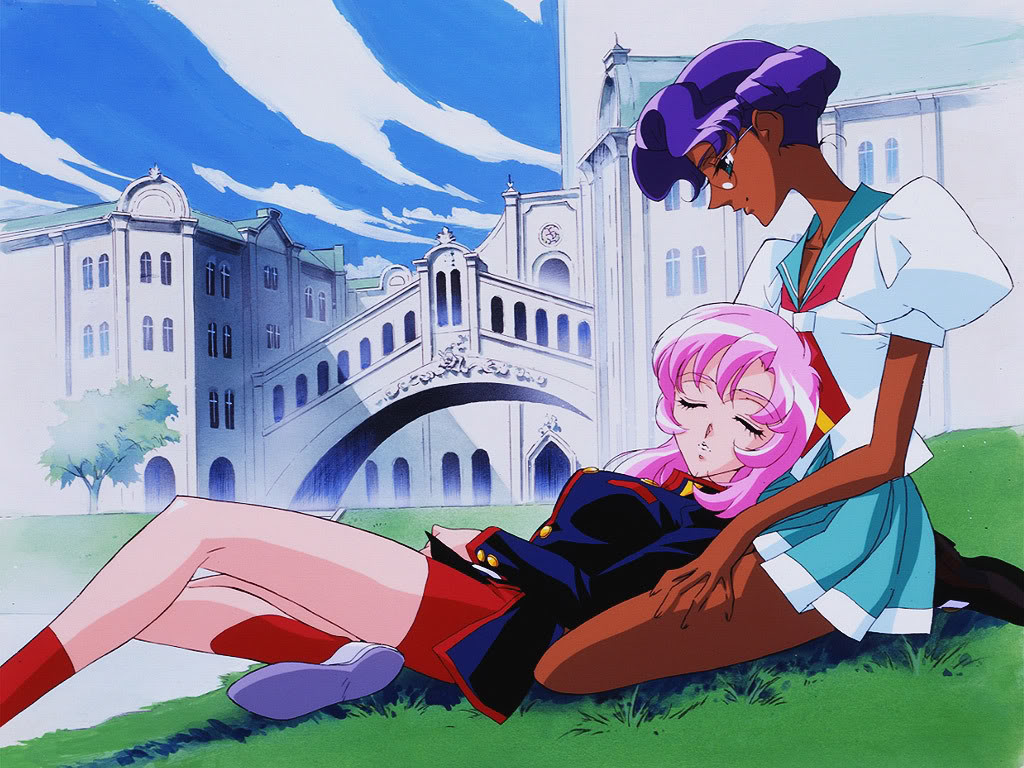

Okay, time for a very brief nutshell summary. Revolutionary Girl Utena, like Evangelion, defies summaries, but here it goes. The original manga was illustrated by Chiho Saito back in 1996 and the anime came out in 1997. The story centers on Utena developing a relationship with another female character, Anthy, amid a complex, symbol laced, conflict. Yeah, I know that is a vague description. Like the article on Sailor Moon, I watched only a few episodes of the anime and read a few issues of the manga at various points of the story. I rely heavily on academic research articles. However, this doesn’t diminish my point: Revolutionary Girl Utena is an important milestone in the history of anime and manga story telling.

Revolutionary Girl Utena is important for anime and manga storytelling because of its empowerment of women, its layer of symbolism, and how it addresses same sex relationships.

Defying Traditional Gender Roles

If you haven’t already read my article on Japanese gender roles, you should. The article provides context for why Sailor Moon and Revolutionary Girl Utena are important. As I mentioned in the introduction, Utena doesn’t foster the idea of the Disney Princess. In fact, Utena is the prince of the story. She dresses like a boy when she undergoes her magical girl transformation and saves people just as the prince would. She even wins the princess Anthy after triumphing over a male in a duel.

If you haven’t already read my article on Japanese gender roles, you should. The article provides context for why Sailor Moon and Revolutionary Girl Utena are important. As I mentioned in the introduction, Utena doesn’t foster the idea of the Disney Princess. In fact, Utena is the prince of the story. She dresses like a boy when she undergoes her magical girl transformation and saves people just as the prince would. She even wins the princess Anthy after triumphing over a male in a duel.

Utena struggles to be herself, her more masculine self, but still be accepted by her peers that expect her to behave as a female should. Utena doesn’t want to become a prince – that is, a male. She isn’t trying to pass as a man and resents being treated as less of a woman because of her masculine traits (she excels at sports, for example). Rather, she wants to adopt the characteristics of a prince: courage, strength, and compassion. Utena doesn’t want to be the princess and have the traits of helplessness, passivity, and be objectified (Bailey, 2012). Anthy takes that role through much of the story.

Utena’s relationship with Anthy also defies traditional gender roles. After all, a woman is supposed to love a man and not another woman. However, the story does not portray their relationship as something taboo or gross. The reader simply realizes this is another act of defiance against societal expectations of women.

Sketching the Symbols of Revolutionary Girl Utena

The layers of symbols found in Utena are important for shojo. It shows that stories aimed at females can be as complex and nuanced as stories aimed at males. The symbols found in this story result of Utena’s focus on the nature of the past, the hold that past has on people, and the relationship between corruption and sexuality (Perper & Cornog, 2006). I won’t go in depth on the symbols and what they mean. That isn’t my focus, and people who have read all of the story are better qualified. The point is the depth the story has. This depth of meaning respects the ability of women to read and think deeply. This should go without saying, but women are often considered less intelligent than men.

The rose is one of the most prominent symbols of the story. Roses are the sexual organs of plants. Traditionally, flowers are stand ins for female sexuality. The “Rose Bride” (Anthy) Utena and the other duelist fight over is the embodiment of romance and female sexuality.The duels take the rose motif to an overtly sexual level. Before the fight, each duelist pulls a sword for their breast (or that of Anthy). These swords are both phallic symbols and represent the manifestation of their heartfelt agony and desire (Haecker, n.d.).

In the rules of the duel, the first person to cut away a rose fitted in each duelist’s breast pocket wins. Hmmm. swords are symbols for the penis; the rose represents the vulva. Alright, I am getting a little too Freudian here. Anyway, the symbols represent how Utena defies her gender role (she uses a sword, a male weapon). The symbols also point to deeper mythological archetypes that trace back through human history to the dawn of human culture.

Alright, I will leave it at that. The rose and the sword are prominent symbols, but there are many others. If you want a deeper analysis, look at Haecker’s article. Perhaps more important than the symbols is the role of same sex relationships.

Revolutionary Girl Utena’s Lesbian Relationships.

How Revolutionary Girl Utena handles same sex relationships is probably its most important contribution to shojo. No, Utena is not a yuri. Sexual orientation isn’t a topic of conversation in the story. Rather, gay and lesbian couples are treated as legitimate and normal. The story lacks anxiety toward Utena’s and Anthy’s attraction (Bailey, 2012).

How Revolutionary Girl Utena handles same sex relationships is probably its most important contribution to shojo. No, Utena is not a yuri. Sexual orientation isn’t a topic of conversation in the story. Rather, gay and lesbian couples are treated as legitimate and normal. The story lacks anxiety toward Utena’s and Anthy’s attraction (Bailey, 2012).

I feel like I keep repeating myself, but each of these three points tie back into each other. Utena’s affection for Anthy rather than a prince defies the role she should be taking as the “princess” of the story. Anthy and Utena’s relationship on the battle field recalls the symbols of the rose and sword as sexual symbols. Together Anthy and Utena summon a legendary sword, illustrating their emotional bond. During Utena’s transformation, Anthy caresses Utena’s face and body (Bailey, 2012).

The focus of the story is on the relationship Utena and Anthy build. Even with the few issues I read of the manga, I could tell their relationship was clearly sexual and based in a deep friendship. Revolutionary Girl Utena shows that lesbians can have deep relationships. The story doesn’t comment on the relationships and treats them as a matter of fact. This is, perhaps, one of the most important elements to the same sex relationships of the story. They are nothing special to comment upon.

The Importance of Revolutionary Girl Utena

Revolutionary Girl Utena is important for showing girls they can be strong, courageous, and otherwise have traits labeled as masculine in society and still embrace their female biology. The story is also important for lesbians to help them come to terms with their identity (Rose, 2013). Utena points out how shojo can be stuffed with as many layers of meanings as shonen like Evangelion. Laying symbols like this helps girls realize that they are as smart as the boys, and stories like this respect their intelligence. This series gives girls strong female protagonists that break traditional molds and feminist molds for that matter.

Together with Sailor Moon, Utena provides girls with an empowering view of what it means to be female, a view that transcends traditional gender roles and relationship expectations. This, in turn, influences future shojo writers.

References

Bailey, C. (2012). Prince Charming by Day, Superheroine by Night? Subversive Sexualities and Gender Fluidity in Revolutionary Girl Utena and Sailor Moon. Colloquy text theory critique 24 .207-222.

Brown, J. (2008). Female Protagonists in Shojo Manage – From Rescuers to the Rescued. Masters Theses 1896. University of Massachusetts.

Haecker, R. (n.d.) An Idealist Interpretation of Revolutionary Girl Utena. https://www.academia.edu/7487606/An_Idealist_Interpretation_of_Revolutionary_Girl_Utena

Perper, T & Cornog, M. (2006) In the Sound of the Bells: Freedom and Revolution in Revolutionary Girl Utena. Mechademia 1. 183-186.

Rose. (2013). “Revolutionary Girl Utena” Transgresses Gender and Sexuality. Autostraddle. http://www.autostraddle.com/revolutionary-girl-utena-transgresses-gender-and-sexuality-204505/

I’m tired of forcing a masculine persona on lesbians. Yes, there are lesbians who behave masculine, but that sterotype is overrepresented and I have a problem with forcing a stereotype on an entire group of people. Aren’t there heterosexual women who defy gender roles too?

There are heterosexual women who defy gender roles, but in order to do so they take on masculine roles to prove how gender roles lack a foundation in biology. In the West we tend to think in duality. Male traits vs. female traits. By this way of thinking, any woman who likes another woman automatically take on male traits (liking a woman is a traditional male trait). The same applies with homosexual men (liking men is a traditional female trait). This stereotyping comes from flawed thinking at the foundation of modern logic. Not all cultures think this way. Sadly, these stereotypes will persist until dualistic, traditional thinking changes.