[This post contains spoilers. I suggest you go watch Cowboy Bebop]

During this revisit, I noticed the more subtle aspects of the story, some of which may be allegorical and symbolic. Before Spike leaves the Bebop to face Vicious, Faye stops him, asking him if he has to go. Jet had just offered Spike the option of walking away too. Spike tells Faye about his artificial eye, the eye he lost when he left the Syndicate the first time. He said it feel as if he sees the past and the present at the same time. During the fight with Vicious, Spike’s human eye is blinded by blood running into it, leaving him to fight using the eye of his past. Quite a nice touch, and one that I hadn’t noticed the first several times I’ve watched the series.

I’ve long liked the dirty, worn feeling that surrounds Cowboy Bebop. All the machines are scratched and dented. Part of his shows how poor the Bebop crew are. Bounty hunting isn’t that lucrative a profession. Yet the battered ships also represent the battered characters and state of humanity. Earth is a wasteland, destroyed by humanity’s hurried push for profit. Humanity has terraformed Mars and various moons, yet the push for profit at all costs remains a key motivation. Humanity is worn by its inability to rise beyond its base instincts. It’s quite a contrast against the optimism of Star Trek, where humanity has mostly risen above its selfish impulses (it only took near annihilation to do so).

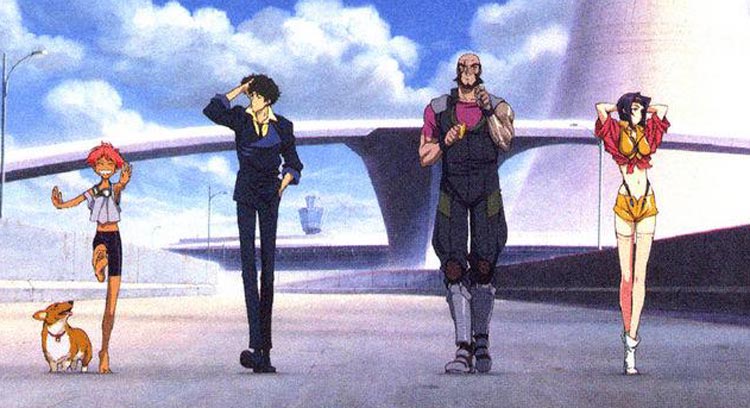

As for the Bebop crew, their bruised ships stand in well for their bruised pasts. Each of the characters have a rough past, filled with mistakes, regrets, lost loves, and burned bridges. Their bodies and souls are as battered as their ships. Yet like those ships, they keep on keeping on. No matter how destroyed the Swordfish, Bebop, or Red Tail are, Jet and the gang are able to put the ships back together. So it is with the characters. No mattered how rough their past was, each character gets up and carries on. They “carry that weight.” Even though Spike dies, he manages to achieve his goal: freedom. He carried the weight of his past to the end without letting it crush his spirit, as evidenced by his final gesture and word: “Bang.”

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Ed. Her eccentric behavior balances the darker characters, but her spirit has the same resilience as her older crew mates. She is the overt representation of their inner nature. Of course, you have to be careful about allegorizing. You can read anything into a symbol when it doesn’t represent anything at all. Ed is just Ed instead of a representation of resilience. Likewise the ships are beat up because it looks cool and captures the entire feel of a dirty, wild space-western. Come to think of it, I don’t often see dented and dinged ship and mecha designs in anime.

Let’s get into speculation. At the end of Bebop, Spike’s entire story arc dies with him. All of the people he associates with are dead. Ed lives with her Father on earth, where AI spy satellites still exist. It is possible she grows up and makes friends with all of these EPU satellites. Then she uses them to clean up the trashed orbit of the earth. Ein could well help her with this as a data dog. As for Jet and Faye, well I surmise they would pair up as Jet and Spike had and continue to hunt bounties. Could they eventually fall in love with each other? It’s possible. Faye is fond of Jet and Spike, even if she wouldn’t admit it. And Jet isn’t so jaded that he can’t fall in love. Of course, this is all speculation. The characters’ story ends with the final credit roll. However, it is fun to consider how their character trajectories could continue into the future. The Syndicate would likely implode into a civil war among many small factions, allowing the police to remove them a little at at time. Tensions between Mars and Ganymede could break into war.

Let me comment on the Netflix version of Cowboy Bebop. I considered writing a separate review, but inevitably I compared it to the original and found it wanting. It looks like Cowboy Bebop, and it offers many Cowboy Bebop frenetic scenes. But it doesn’t feel like Bebop. The characters are a bit too different, particularly Faye. Mustafa Shakir nails Jet, but his performance makes you want Spike and, especially, Faye to be more like their anime inspiration. The Netflix version is an inspired spin of the original more than a retelling, but at times, it can’t decide if it wants to be a retelling or if it wants to be it’s own story. Vicious hurts. His scenes are among the worst, and there’s too many of them. Vicious works in the original series because he has few lines and few scenes. Gren, too, loses his importance as a character. He shows up more often, but in the first season, he lacks the impact on Faye he has in the original. In the original, Gren reveals Vicious’s character, reveals important world building elements, and changes Faye in the encounter. So far, the Netflix Gren is a missed opportunity. Basically, the Netflix version of Cowboy Bebop often misses what makes the original a classic. We won’t be discussing this version’s merits decades from now.

The sad ending of the original Cowboy Bebop follows the thread that underlays the series. There’s a melancholy under everything, but it isn’t a hopeless one. It’s a sadness centered on a love for life and an acceptance that it will end, a sadness that creates gusto at times and despair in others. However, all of it is the same feeling. You can’t understand happiness without sorrow, after all. If Cowboy Bebop had ended with the characters riding into the sunset, with a happy ending, I doubt we would still be discussing it decades later.

See you space cowboy.

Had the underlying Japanese philosophical perspective been created by a contemporary Western philosopher, it would have been Nietzsche. There’s a fatalistic perspective woven into Japanese thought, a “shō ga nai” to one’s destiny as predetermined by some in-alterable past. Each of Cowboy Bebop’s characters is tightly held within the confines of his or her own history. Faye doesn’t recognize the gift of re-invention afforded by her own lack of historical identity until it’s too late, and then even she finds that there’s no way back.

Recently reading the words of the early 20th-century female Japanese anarchists, Kaneko Fumiko and Kanno Sugako, as they either planned or awaited their own deaths, both seemed to express an almost romanticized sense of inevitable closure. Likewise, Spike was engaged in “shinjū”, the determined suicide of one bound by impossible love. As for the others, they’re likewise “cowboys”. Their only choices are whether to meet their own destinies head on, or merely to continue following the gravy train through a wilderness.

As for the Netflix remake (which I haven’t seen), “Ghost in the Shell” left me convinced that there’s a deep disconnect between the character-driven patterns of East Asian story-telling and archetypical Western expectations. I thought the “non-ending” of the anime was brutally clear. Westerners, however demand a conclusion, or a hero, or at least a “happy ending” for someone. But that’s not the point of the Asian perspective, where a deep understanding of the characters is sufficient.

I agree that Western versions of anime and Japanese stories have a disconnect with the philosophy of the East. Many people mistake the acceptance of fate (amor fati, in our Western tradition) as a type of nihlism instead of simply accepting the law of cause and effect. “Ghost in the Shell” had the action but not the philosophical soul that makes the series great. Netflix’s Cowboy Bebop suffers from the same problem. It’s as if Western film writers are afraid to make a story that too intelligent or philosophical.