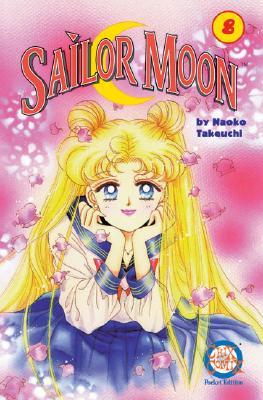

It came to my attention that JP is biased. We often focus on shonen and more male oriented topics. When I initially planned this series of anime/manga that changed the medium, Sailor Moon wasn’t on the list. After thinking about it, I realized how wrong this was. Sailor Moon is one of the most important series.

But it was also something I knew nothing about.

As an academic, I am used to studying things that I do not like. Sailor Moon doesn’t appeal to me, but the importance of the show drove me to research it anyway. So, I dug in and watched a few episodes and read some of the manga issues. Basically, I am saying my understanding of the series is limited, and I will likely get some plot points wrong. However, we must look at this important manga series.

Sailor Moon is the most complicated manga/anime I researched for this article series. Fair warning: this article will be long. There are mixed views about the series. Some researchers consider the magical girl genre to be nothing more than a commodification of girlhood. Others see the genre, and Sailor Moon in particular, as a way of empowering girls. However, that empowerment is quickly lost as she grows into adolescence. Others see the series as positive impact on girls and the medium of manga/anime in general. I agree with this view. I will touch on the negative views, but I will also show how Sailor Moon breaks the trends of the magical girl genre and stories aimed at young girls in general.

Sailor Moon is the most complicated manga/anime I researched for this article series. Fair warning: this article will be long. There are mixed views about the series. Some researchers consider the magical girl genre to be nothing more than a commodification of girlhood. Others see the genre, and Sailor Moon in particular, as a way of empowering girls. However, that empowerment is quickly lost as she grows into adolescence. Others see the series as positive impact on girls and the medium of manga/anime in general. I agree with this view. I will touch on the negative views, but I will also show how Sailor Moon breaks the trends of the magical girl genre and stories aimed at young girls in general.

Sailor Moon encourages a different set of values for girls than most other stories: those of female friendship, confidence, inner strength, and independence. The series relegates males to support characters and even liabilities rather than having men as the final goal of the girl. Prince Charming does not ride in to save the day.

*Cracks knuckles* Let’s get started.

Girls, Magic, and Money

The magical girl genre (called maho shojo or majokko) appeared in the 1960s (Saito, 2014) . The genre specifically targets prepubescent girls much like My Little Pony and Barbie does here in the States. In the genre, an ordinary girl discovers the ability to turn into a supergirl. Using her powers she faces villains and saves the day in addition to going to school and doing chores. Behind the seeming empowering theme is money. Many magical girl stories are designed to sell toys and other merchandise to girls aged 4 – 9 years old ( Saito, 2014). American shows like Barbie and Transformers are designed with the same goals in mind.

Many magical girl stories actually encourage traditional gender roles despite the surface story of girl power. Some researchers consider this true with Sailor Moon as well. This covert encouragement then ties back to selling merchandise associated with traditional ideas of romance and domestic life in adolescence. How can these cute, powerful girls actually encourage becoming a traditional wife?

Contrast.

Some researchers argue that the typical villains of magical girl stories – adult women wearing heavy makeup and obsessed with careerism – are failed women. That is why they are villains. They failed to become a wife or a mother. These villains also dress poorly compared to the cute fashion of the heroines. So through contrast, magical girl stories are thought to teach the need to consume fashion and avoid becoming a “failed woman” by being the opposite: a fashionable romantic woman who wants to become a good wife and mother (Saito, 2014). These ideas tie back into money and consumerism. The message teaches girls to avoid becoming these villains. So they need to dress cute, and use makeup well. While I can somewhat see this argument, I do not agree that it extends to Sailor Moon.

I need to point out a difference between maho shojo and majokko. Maho Shojo are stories where a 9-14 year old girl accidentally gains supernatural powers. Majokko has the girl gaining her powers because she is a princess of a magical kingdom or a similar situation (Saito, 2014). Both story types feature a transformation that changes a mediocre girl destined for a traditional life to a superhero who can help and protect those she cares about.

Shattering the Moon

Sailor Moon shatters and iconifies the magical girl conventions. The story certainly leverages the genre’s tropes and story lines. However, Sailor Moon takes romance and pushes it into a subplot. The focus of the story is friendship between girls and personal growth. Usagi (Sailor Moon), becomes a confident person through the use of her powers. She goes from being a self proclaimed cry-baby that is lazy, eats too much, and does poorly at school to the key team member of the Sailor Soldier team. Usagi is designed to be the most identifiable character. She dislikes homework; she frets about her weight. Although, this fretting can be annoying I am told. Usagi, like all the Sailor Moon girls, are drawn thin and athletic. The design doesn’t show how she needs to worry about weight. In fact, the author originally wanted to draw Usagi as chubbier. However, she could not move away from her design tastes (Animerica, 1996).

Sailor Moon shatters and iconifies the magical girl conventions. The story certainly leverages the genre’s tropes and story lines. However, Sailor Moon takes romance and pushes it into a subplot. The focus of the story is friendship between girls and personal growth. Usagi (Sailor Moon), becomes a confident person through the use of her powers. She goes from being a self proclaimed cry-baby that is lazy, eats too much, and does poorly at school to the key team member of the Sailor Soldier team. Usagi is designed to be the most identifiable character. She dislikes homework; she frets about her weight. Although, this fretting can be annoying I am told. Usagi, like all the Sailor Moon girls, are drawn thin and athletic. The design doesn’t show how she needs to worry about weight. In fact, the author originally wanted to draw Usagi as chubbier. However, she could not move away from her design tastes (Animerica, 1996).

Anyway, the point is each of the characters in Sailor Moon have their own appeal. The author, Naoko Takeuchi, resisted pressure to make her Sailor heroines fit into manga stereotypes (the fat one, the nerdy one, and others). Although she does give each girl specific traits, these traits are not the whole of their identities. Naoko wanted the central focus of the story to be the friendship between the Sailor Soldiers. Likewise, she wanted the story to tell girls they can be independent and happy regardless of having boyfriends or not (Animerica, 1996).

Takeuchi (1998) writes this message in the very first volume of the manga:

We girls have to be strong, OK? You see, we have to protect the guys we love.

This message challenges the the typical idea that a princess needs to be protected by a prince. The message also proved to be immensely popular with girls. Sailor Moon appeared in 1992 as an anime. By 1995, the show debuted in the United States. It was already the number one children action-adventure show in Japan, France, Italy, Spain, and Hong Kong. The show also aired in Taiwan, Korea, Scandinavia, and Thailand (Grigsby, 1998).

Takeuchi also empowers girls by providing balance to her messages. The point she makes in Sailor Moon is how girls do not need boys to be complete. Girls do not need to avoid men to be whole persons. Later in the series, Usagi chooses to be a homemaker and even has a daughter. Yet, this has no bearing on her ability to be a superheroine. Usagi’s decision also means a woman does not have to give up everything to be a mother. The idea smacks the face of traditional Japanese values (and to some extent American values) that when a woman becomes a wife and homemaker, that becomes her entire identity. She gives up everything else.

Challenging traditional gender roles and telling girls it is equally okay to be a wife and mother or stay independent revolutionized stories aimed at young girls. While other magical girl stories touched on these ideas, Sailor Moon put them together in a way that proved internationally popular.

Lesbian Superheroines

Sailor Moon also introduces gender fluidity in two lesbian superheroines: Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune. The pair create a rift between the manga and the anime. In the manga, their relationship has zero influence on how the other girls treat them. The relationship goes unnoticed (Bailey, 2012). However, the manga does play with questions of Sailor Uranus’s, Haruka’s, gender. Haruka is masculine in every traditional way: outspoken, athletic and wears a male school uniform. Some researchers suggest Haruka can be read as a female-to-male transgendered person. However, in the story she doesn’t express desire to be male. Rather she cares little about what others think of her. Haruka serves as commentary about people’s hang ups on gender (Bailey 2012). Haruka is the overt version of Takeuchi’s message that being female does not limit a person. Haruka even states this in volume 22 (Takeuchi, 2000):

Sailor Moon also introduces gender fluidity in two lesbian superheroines: Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune. The pair create a rift between the manga and the anime. In the manga, their relationship has zero influence on how the other girls treat them. The relationship goes unnoticed (Bailey, 2012). However, the manga does play with questions of Sailor Uranus’s, Haruka’s, gender. Haruka is masculine in every traditional way: outspoken, athletic and wears a male school uniform. Some researchers suggest Haruka can be read as a female-to-male transgendered person. However, in the story she doesn’t express desire to be male. Rather she cares little about what others think of her. Haruka serves as commentary about people’s hang ups on gender (Bailey 2012). Haruka is the overt version of Takeuchi’s message that being female does not limit a person. Haruka even states this in volume 22 (Takeuchi, 2000):

Do you think just because you’re a girl you’re always going to lose to a guy? If you think that, you can’t protect the ones you love.

Haruka is an empowering character that shows how gender labels are not reality. Unfortunately, whereas in the manga Usagi befriends Haruka and accepts the girl as she is, in the anime Usagi and friends express extreme disgust about their former attraction to their idea of a male Haruka (Bailey, 2012). The lesbian relationship (which was just a matter of fact in the manga) is met with teasing and treated as strange. Other translations go as far as eliminating the relationship between Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune. In North America, they are cousins (Bailey, 2012).

Criticisms

Because of its popularity, Sailor Moon attracts criticisms as I briefly touched upon in the introduction. Some feminists see the story as covertly encouraging traditional gender roles. After all, Usagi eventually becomes a homemaker!

They are missing the point. Takeuchi shows how girls do not need men to be complete, but she also shows how girls do not need to avoid men to be complete. Who each of the girls are is independent of their relationships (or lack thereof) with men. The contrast between the villains, who appear to be failed career women, and the heroines points to this idea. The villains are not complete people: they are not satisfied with themselves and that is what drives them to be villains. The thick make up and skimpy outfits all point to the early female villains being dissatisfied and focused on external validation.

Another criticism leveled on Sailor Moon is how commercial it is. As I mentioned earlier, magical girl stories were often designed to sell merchandise. This isn’t necessary bad. Sailor Moon‘s ability to sell merchandise spawned copy cats with similar messages. While commodification is tired, it is not surprising. Most of the shows I grew up watching, Gi-Joe, Transformers, Thundercats, and others, were all designed to sell toys. It is simply unavoidable. Unlike the shows I watched and many other magical girl stories, Sailor Moon has a focused message beyond simply selling stuff.

Sailor Moon, at least the anime, attracts criticism for trying to appeal to both prepubescent girls and young adult men. Some researchers consider the Sailor Moon girls as sexual objects designed to sell merchandise and fantasies to both young girls and older men (Grisby, 1998; Saito, 2014). Saito (2014) suggests the appeal to adult men is a result of men resisting gendered responsibilities. In other words, guys are tired of being expected to act in certain “male” ways. While these arguments may have some weight, and there is a problem with men sexualizing teens, these arguments distract us from the important messages Sailor Moon teaches girls.

The Importance of Sailor Moon

Okay, after such a long article it is time to summarize why Sailor Moon is important. Sailor Moon changed magical girl stories and other stories aimed at girls. Where magical girl stories mostly focused on love, romance, and family, Sailor Moon presents girls as independent superheroines that do not need men to protect them (Grisby, 1998). They embrace their femininity and girlhood, but they do not let it entirely define them.

Sailor Moon provides role models that go far beyond the often helpless Disney princesses and teach girls they are not limited by societal labels. They are free to be complete people even if they choose to be homemakers. Their identities are not limited by gender roles.

Sailor Moon changed how stories designed for girls are told. It proved that romance doesn’t have to be a focus. Male characters like Tuxedo Mask are often liabilities and often cause trouble for the Sailor Girls. This is a drastic shift from Prince Charming riding in to save the day. Sailor Moon influenced several generations of girls – telling them they can be strong, independent, and smart in their own right. Sailor Moon taught girls to look beyond gender labels and not let them define them. The series opened the door for other empowering, girl centered stories. Sailor Moon, more than any other magical girl story, taught girls that being a girl is great.

References

Animerica (1996). Interview with Takeuchi Naoko. Animerica. 4[8].

Brown, J. (2008). Female Protagonists in Shōjo Manga – From the Rescuers to the Rescued. Masters Theses 1896 – February 2014. Paper 137.

Bailey, C. E. (2012). Prince Charming by Day, Superheroine by Night? Subversive Sexualities and Gender Fluidity in Revolutionary Girl Utena and Sailor Moon. Colloquy: Text Theory Critique, (24), 207-222.

Grigsby, M. (1998). Sailormoon: Manga (Comics) and Anime (Cartoon) Superheroine Meets Barbie: Global Entertainment Commodity Comes to the United States. Journal Of Popular Culture, 32(1), 59-80.

Saito, K. (2014). Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenges

of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society . The Journal of Asian Studies, 73, pp

143-164 doi:10.1017/S0021911813001708.

Takeuchi, N. (1998) Sailor Moon Vol. 1. Tokyo Pop.

Takeuchi, N. (2000). Sailor Moon Vol. 22. Tokyo Pop.

I also wanted to comment on the supposed “disgust” towards Haruka and Michiru… this is also very obviously not true? Usagi and other characters from the inner senshi express attraction towards Haruka before they are aware she is a woman, but even after they realize she is a woman, it is a recurring scenario for Haruka to flirt with them and for them to blush in kind. If anything, it is pretty remarkable how casually positive both the manga and anime are towards varying expressions of gender and sexuality.

I read the Bailey paper that you referenced but your interpretation of it is pretty shallow and reductive. You read it and paraphrased it without really even understanding both the paper and its source material. From Bailey’s paper:

“In fact, in the manga, it nearly goes unnoticed. The issue of the couple’s “lesbianism” is never brought up in conversation. Haruka’s and Michiru’s relationship is treated like any other and is portrayed as long-term, loving, and sustainable.”

Bailey’s paper then contrasts that with the anime, where the girls express more confusion and a more explicit desire to know over an exact gender for Haruka. Haruka’s response is vague, which is meant to illustrate that her gender is fluid and not limited by the other characters’ more narrow definitions of gender. To call it homophobic is a little unkind I think, their reactions are more likely meant to be a dramatic and sometimes comedic foil to Haruka’s unconventional expressions. The inner senshi are obviously portrayed as more naive, more childlike, and less worldly than their outer senshi counterparts, and that point is made clear many many times throughout the anime.

Thank you for your thoughts!

You are correct that I didn’t research this article as I would normally. I stated my limitations in the beginning. You’re right: I was, and still am, an outsider to the series. Instead, I relied heavily on a friend who was a life-long fan of the series. But the goal of the article was to spark conversation and thought, so I suppose it hit its goal. Considering the importance of the series, I really should give it a dedicated watch. Would you recommend the original series or the recent remake?

Ehm.. I just want to point out that Usagi (aka Sailor Moon) does not end up as a housewife neither in the manga neither in the anime. She ends up being the queen of the world (Aka Neo Queen Serenity) and it is stated that her husband will stay home to look after the children and do the housework while she is off to save the world. Also I can’t recall any of the girls are disgusted by Uranus or Neptune. (Maybe it was played like that in the north american dub, IDK since i am not from the states) In fact they were portrayed to be attracted to them and they were portrayed to be people they desire to be rather than people disgusted by.

I hadn’t seen all of the show or read all of the manga, so I relied on my academic sources. According to the sources, Usagi dreams of being a wife, but that in no way limits her ability to be a superheroine. Perhaps I confused her dream with her becoming a homemaker?

Bailey (2012) states the American version of the anime has some reservations toward Uranus and Neptune’s relationship. There are some localization differences between countries from what the sources state.

I felt this was not a really well researched post and from a very much outsider viewpoint.

I came across this randomly and I know this post is old but at no point does Usagi say she wants to be a homemaker. However, Makoto (sailor Jupiter) does explicitly make this sentiment, and it is meant to be a surprising contrast; when Makoto is originally introduced to the cast, she is perceived as a delinquent because she is tall, tough, and good at physical combat. You later find out she is also very into cooking, gardening, and homemaking and wants to be a good wife one day.

Now I need to watch it again. Thank you for this article.

Thanks for your interest. Sometimes it is nice to revisit a story. You can have a different perspective and appreciate the story differently.