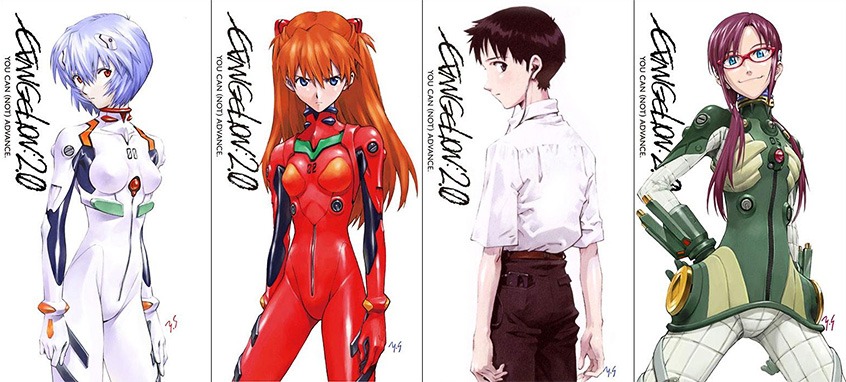

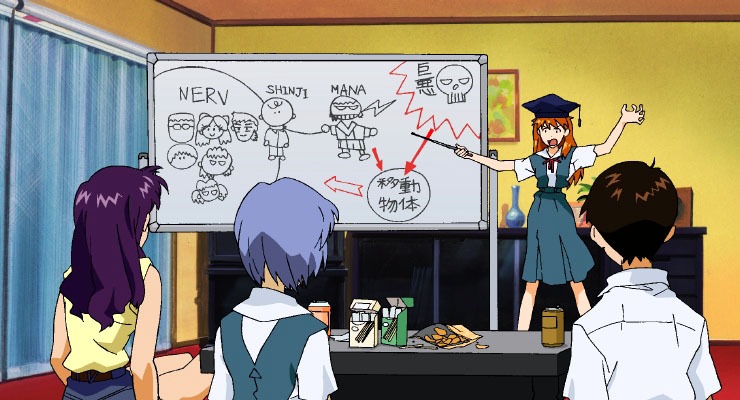

As I watched Neon Genesis Evangelion again, I wondered what more I could say about it. After all, it is perhaps the most analyzed anime. I’ve written about Eva and examined Shinji. The influence of the anime can’t be denied. Anime could be considered BE (Before Eva) and AE (After Eva), especially inside the mecha genre. The story is constantly referenced and popularized many of the tropes we now have: the broken hero who doesn’t really rise to the label of hero; the doll-like character who represents all the projections of another character (who also pushed moe designs forward); the almost-nonsensical cosmic twists to the story. Every anime fan knows of Eva, whether you like the anime or not.

So what more could I add? Nothing deep. Nothing but my new impression of the story.

As I watched, it struck me that the ending of the TV series, which made it (in)famous happened more-or-less by accident; Eva suffered from budget problems at the end, which is why the animation degraded to storyboard scenes and title cards to save money. It created a postmodern feel that helped set the anime apart. The ending episodes in the film The End of Evangelion basically ignored the final episodes of the series and how Shinji came to some understanding and truce with himself, which suggests how the team may have ended the TV series if the budget had lasted.

The word strange kept popping up in my mind as I watched, and I wondered how Evangelion would’ve played without the quasi-mythological elements in the End of Eva. While the character development continued to carry through–and I rather liked the fact the characters never healed because of the realism and literary commentary that implied–the quasi-mythology overshadowed the careful character development. Later mecha like Eureka Seven avoided this overshadowing problem. Frankly, I found the ending chapters of Eva a mess. However, I dislike postmodern stories because they offer deconstruction but never leverage the observations and realizations deconstruction can bring. Many postmodern stories just leave you hanging, without the “life continues” ending anime likes to use or other definitive endings. Instead, many postmodern stories feel like someone dumped a box of Lego and walked away. The lead up to the finale kept my interest. Shinji, Asuka, and Rei remained interesting with how just as they began emotionally healing events reopened the wounds. Shinji’s self-pitying, self-centeredness continued to irritate me. I found Asuka and Rei’s characters more interesting. All three characters represented how people handle bad events. People shut down (Shinji). People rage and fight (Asuka). People wall themselves off and accept their lack of power (Rei). All three were forced out of their coping mechanisms by events. If anything, Rei took on the typical role of a hero in her own strange way.

The animation team used many clever techniques to save money. While you do see some recycled frames, especially during the finale of the TV show, most cost cutting involved still shots. While the still shots serve as great dramatic effect, they often extend into several minutes. A single frame running for a minute can save 1,440 drawings, assuming 24 frames per second. Throughout Evangelion, I noticed still frames of Shinji’s dad and other characters extending a few seconds. Some of those frames were also recycled. Likewise, several scenes animated only the character’s mouths or panned a still frame. Evangelion didn’t do anything unusual for the time. The mouth animation in a relatively still frame had been a technique you’d see in Pokemon and Speed Racer. But Eva used the techniques, particularly the stills, to aid drama and push the story. The still frames often had important audio and character development. Perhaps the longest running example of this was the off-screen sex scene between Misato and Ryoji. The scene couldn’t have been shown because of content restrictions, but the scene also conserved quite a few frames. These rather subtle methods to reduce costs were clever.

I enjoyed the revisit to Evangelion. It remained a difficult work with its layers and postmodern ending. Did I like it more than the more recent movie rehashes (1.11, 2.22, 3.33)? Yes and no. I liked the higher production value and gloss of the movies. I also liked how cohesive the movies felt. However, the original series had better character development (because of its longer run time) than I remembered. The movies explored areas the original series only mentioned. So I would say I liked each equally. They complimented each other well.

Is Neon Genesis Evangelion still watchable? Yes. As with any classic work, it focuses on timeless themes of human character. However, the style and limitation of the animation may turn off many younger anime fans. It lacks the polish and gloss of modern anime. Anime from the 1990s has the same problem as video games from the era: they don’t have the flash of modern media, which prevents many from seeing their substance. The still frames in particular will make many modern watchers impatient. The drama of visual silence (while a Beethoven symphony plays) might make many used to constant movement squirm with impatience. I’d like to see more moments of visual silence in modern anime and movies. You can’t understand words without spaces–well, unless you are learning Japanese, which in my view the language would benefit from spaces between words. Silence punctuates messages and offers you a chance to reflect on what happened in a scene. Evangelion offers many chances to practice reflection. While these reflective scenes may have been came out of budget constraints, they act as punctuation and spaces between Eva’s sentences. Eva isn’t the only story that has these visual punctuation marks. The technique works against the trend of cut-cut-cut, go-go-go in media. When watching many modern American stories, the constant cuts and camera movement can trigger vertigo. Slower media, moving away from Tiktok and other micro-video, would do all our minds well. Perhaps in the future we will see media that returns to Eva-like visual punctuation marks as people backlash against the erosion of our attention spans.