When Horimiya: Pieces released, I decided to revisit the original season. My original observations still hold. The series offers a heartfelt, nostalgic feeling toward growing up. For those of us who, like me, worked all the time and didn’t have the social interactions of high school or college for that matter, there’s a pleasant vicariousness to the story. Of course, you have to be careful of this: it might make you feel regret or envy if you lack the right perspective with stories like this.

During my revisit, the behaviors of the male characters stood out to me. I grew up in an area that has definite views of how men are to act. Many of the guys in Horimiya act in ways the old-fashioned men in my area would call “gay”. They mean no insult–usually. Rather, the men I know have a limited vocabulary, which is a part of their definition of manhood. Men are to be of few words, stoic (as opposed to Stoic, the philosophy), and not expressive of their wants or emotions. They lack the words to express their emotions even when they wish to. This traditional idea of masculinity, which isn’t traditional at all if you read history, clashes against the softer men of Horimiya. So any man who is more emotionally connected is “gay.”

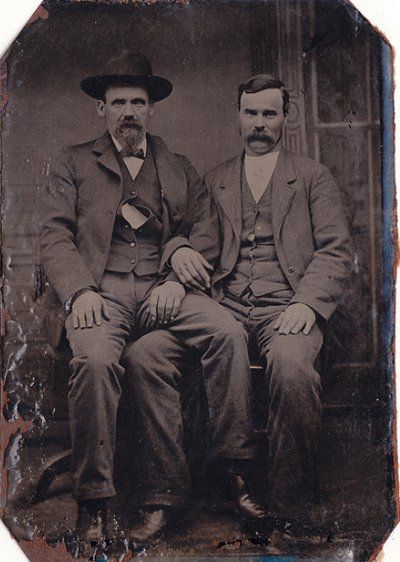

The men of the anime have a willingness to speak of their emotions and often do so directly. They understand, at least part of the time, the emotional cues of their female love interests and the expressions of friendship they have with each other. If you’ve ever seen old friend photographs from the American 1800s, you will see similar displays of intimacy. Many people today assume these photos were of gay couples. And in some cases the assumption is right, but not in all cases. In Horimiya all the men are straight and have girlfriends, yet they exhibit “gayness” to their friendships with each other.

The rise of the homosexual community has hurt the ability of heterosexual men to express affection toward their friends. This says more about heterosexual men than the gay community. The gay community’s expression of romantic emotions has hurt the heterosexual man’s ability to express love toward friends because of how heterosexuals often define themselves as “not gay.” Whenever I hear men in my area speak of “gays” they are defining themselves as opposite to that community. This means many men I know can’t express their emotions, even toward their wives and girlfriends, in ways that aren’t “masculine”. This creates an unhealthy emotional and communication style for the silly reason of not appearing gay. This perspective isn’t limited to the older generations. Rural areas have definitive boundaries between groups.

The male characters in Horimiya don’t have these hangups, so they offer a healthier emotional template for young men than the template I grew up with. Male friendships shouldn’t have any hesitation toward expressing their feelings just out of fear of appearing “gay”. I use quotations around that word because the view has nothing to do with the actual gay community, but rather the “opposite of a manly man” the word represents to old-fashioned masculine men. Horimiya may be entertainment, but it offers a perspective on open, emotion communication many young men wouldn’t be exposed to otherwise. Most anime rom-coms leverage the masculine inability to communicate emotions as a comedic plot point. Horimiya refreshes in its opposite approach, but the story shows how difficult such communication can be too. Being open with people close to you is a risk. Those closest to you can hurt you the most. They know your weaknesses and soft spots, yet without such openness and trust, deep friendships and romance cannot happen.

Horimiya plays some of its jokes on how open the boys can be. Hori, for example, worries more about losing Miyamura to one of the guys than to another girl. Miyamura has eyes only for her, but the jokes point toward how male emotional openness among each other can feel odd outside of homosexual romantic contexts. These jokes offer good satire for the modern perspective of men. Ironically, at least among the women I’ve known, softer men like in Horimiya are deemed as more attractive than the macho, stoic masculinity men believe women find attractive. Of course, this comes down to individual tastes.

In many ways, stories like Horimiya offers a glimpse at what an alternative reality could look like if the macho, stoic masculinity hadn’t taken hold. Interestingly, the ideas of this version of masculinity have no basis in history. Samurai would write of crying when their friends or wives died. Marcus Aurelius wrote of his pain when people close to him died or betrayed him. He wrote affectionately of his father, teachers, and friends. The letters of Hideyoshi to his first wife have affection within them. The one-dimensional, modern view of men lacks a historical foundation.

Okay, I’ve soapboxed long enough. Horimiya’s focus on everyday small amusements, like being a little scatterbrained or sharing a dessert, offers a good lesson on how daily life offers treasures if we pay attention. Horimiya, like many anime and manga, ties into this aspect of Japanese literature. This focus on the mundane treasures of life keeps me coming back to Japan’s stories. Horimiya, in particular, shows the fun and magic of everyday, often-forgotten events. During my rewatch, I enjoyed the series as much as the first time I watched it. I had watched it back in 2021, and it continued to resurface in my thoughts. That’s the mark of a good story. Despite being a comedy, there’s a lot of heart and emotional intelligence to the story. The dub is quite good. I had watched the subtitled version the first time. Some of the jokes and character interactions feel a bit strange, but the characters all have distinct personalities that add to the antics. Pieces is worth a watch. The episode where Hori was troubled by the scent of other people on Miyamura reminded me of a similar situation I had with a past girlfriend who had a sensitive nose. Far-fetched antics aren’t so far-fetched. If you enjoy rom-coms or slice-of-life, Horimiya will keep you entertained.