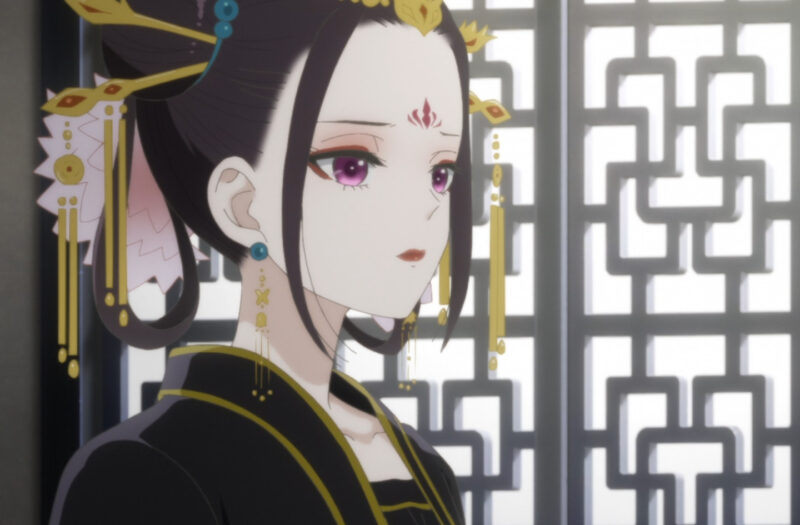

Raven of the Inner Palace wowed me on many levels when I gave it a watch. While the animation is stiff, especially compared to the experimental animation of Bocchi the Rock! and the lovely fluid animation of Do it Yourself!!, it is beautiful. The detailed stiffness works well with the guarded feel of the characters and the hidden layers of the characters. Raven of the Inner Palace takes place in the Forbidden Palace of China. It follows a mystery-of-the-week format similar to Scooby Doo. The Raven Consort, Liu Shouxue, has the ability to see the dead and to send them to the afterlife. She also has other magical abilities which terrifies most of the other residents of the Forbidden Palace. Despite being a consort, she is equal to the Emperor, who finds her fascinating and dangerous. She doesn’t have “nighttime responsibilities,” as the opening introductions emphasize. As the story progresses, you soon understand Shouxue’s strange status.

As the Raven Consort, Shouxue stands apart from everyone. Her predecessor lived and died alone with the exception of raising Shouxue as the next Raven Consort. Because of this isolation, Shouxue is naive and innocent despite her deep understanding death and pain. Although she is supposed to remain apart, over the course of the story Shouxue gains friends among the women and eunuchs of the palace.

Raven of the Inner Palace hides many levels of darkness surrounding its mysteries, particularly among those eunuchs. If you aren’t familiar with this part of Chinese history, for men to work at the Forbidden Palace, they had to become eunuchs. Many would choose to do this in return for a chance at position and stability. Others were forced. This was done so the Emperor’s harem and the other nobility didn’t have to worry about dalliances with their wives and daughters. Raven embraces the horror of this practice, including accounts of the eunuchs being raped and brutalized by their handlers. Below is an account of the procedure (Stent, 1877):

The operation is performed in this manner:–white ligatures or bandages are bound tightly round the lower part of the belly and the upper parts of the thighs, to prevent too much hemorrhage. The parts about to be operated on are then bathed three times with hot pepper-water, the intended eunuch being in the reclining position as previously described. When the parts have been sufficiently bathed, the whole,–both testicles and penis–are cut off as closely as possible with a small curved knife, something in the shape of a sickle. The emasculation being effected, a pewter needle or spigot is carefully thrust into the main orifice at the root of the penis; the wound is then covered with paper saturated in cold water and is carefully bound up. After the wound is dressed the patient is made to walk about the room, supported by two of the “knifers,” for two or three hours, when he is allowed to lie down.

The patient is not allowed to drink anything for three days, during which time he often suffers great agony, not only from thirst, but from intense pain, and from the impossibility of relieving nature during that period.

At the end of three days the bandage is taken off, the spigot is pulled out, and the sufferer obtains relief in the copious flow of urine which spurts out like a fountain. If this takes place satisfactorily, the patient is considered out of danger and congratulated on it; but if the unfortunate wretch cannot make water he is doomed to a death of agony, for the passages have become swollen and nothing can save him.

We don’t know what the survival rate was for this procedure (Jay, 1993). Raven delves into the world of the survivors, the scars these men carry when forced to become eunuchs. It even goes into what young boys endure. Beneath the beautiful details and costumes sits all of these evils which slowly reveal as Shouxue solves each mystery-of-the-week.

Shouxue appears as a savior for men of all ages, including the Emperor. She becomes an emotional sanctuary for the eunuchs that surround her and cannot find emotional acceptance or understanding anywhere except with her. For her part, Shouxue comes to understand these men’s emotional needs, and this breaks her out of her isolation as the Raven Consort. This theme of the female savior appears throughout anime, but in Raven it plays a critical role in the character arcs of the men around Shouxue. Throughout studies I’ve read, men need women to be mentally healthy. Men need women’s emotional intelligence. Shouxue takes on this responsibility without resistance or resentment; she cares about the men who surround her. Raven doubles down on this to create a small point of light amid the darkness of its male characters’ stories. This theme and dynamic proved to be the most interesting part of Raven for me. The mystery-of-the-week often hooked into these undercurrents of brokenness.

Raven of the Inner Palace has a lot of pain and violence under its civilized facade. The darkness isn’t unrelenting. Shouxue develops a sisterhood with her lady-in-waiting Jiu-jiu who brings levity to the story. Shouxue also becomes the younger sister of the Second Consort, which provides a different perspective on emotional needs among those who are trapped by status and position.

There’s a lot going on in Raven of the Inner Palace. The layers of conflict and hurt take time to bubble to the surface. These long-running arcs tie the mystery-of-the-week format together. The anime makes me wonder how the light novels read, considering the anime only covers a handful of chapters from the first volumes. Hints and suggestions pervade Raven of the Inner Palace, so you have to pay attention while you watch. The female savior theme becomes particularly poignant when you consider the history of Chinese eunuchs, which wasn’t too far from the dramatized experiences of Shouxue’s friends.

The anime has problems, like any story. The stiffness of the animation and the repeated frames of Shouxue’s spellcasting stand out. The pacing of the mysteries felt off sometimes too. Some were too easily solved, but the slow unfurling of the sub-characters’ experiences helped blunt these too-easy solutions. The literary feel of the story kept me watching. The theme song Natsu no Yuki by Krage captured the story well.

References

Jay, J. W. (1993). Another side of Chinese eunuch history: Castration, marriage, adoption, and burial. Canadian Journal of History, 28(3), 459. https://doi-org.oh0164.oplin.org/10.3138/cjh.28.3.459

Stent, G. Carter, Chinese Eunuchs, Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 11, 1877.