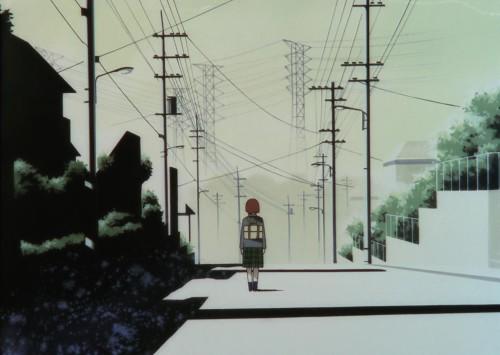

Have you wondered why anime shows power lines with cicada chirping in the background?

Power lines and cicadas seem to be a strange association, but for many, overhead power lines are a part of home. They are a common sight in Japanese towns and cities . Unlike many countries where power grids are underground, the majority of Japan’s power lines are above ground (Baseel, 2014). Because power lines are a part of the landscape, anime likes to show them with the sounds of cicada to evoke the feeling of summer heat. It is a way of establishing an atmosphere. Such scenes can create feelings of nostalgia. Slice-of-life anime shows power lines during happy and sad moments in the story. This isn’t filler. Writers do this to emphasize the fragile nature of the moment. It associates the event with familiar sights of home. The moment of non-action hammers the impact.

Power lines lack meaning outside of setting atmosphere, establishing place, and providing a reflective moment. The sound of cicada that plays during these scenes allows power line scenes to work. The cicada has a long history as the symbol of summer. The noisy bug appears throughout Japanese literature.

Where the cicada casts her shell

In the shadows of the tree,

There is one whom I love well,

Though her heart is cold to me.-Tale of Genji

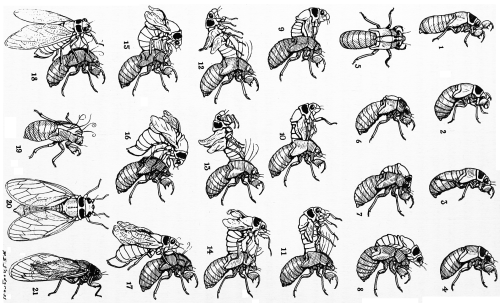

Some species of cicada spend between 13 and 17 years (!) underground before emerging, molting, and mating. They spend all but a few weeks underground as a vampire. The nymph attaches to tree roots and guzzle sap. Once they emerge and molt for the 5th time in their lives, they live only 3-4 weeks (Milius, 2013). Males make all the noise. Girls sit back and pick the best drummer. Males have a membrane on their abdomen called a tymbal. Vibrating this membrane creates their characteristic loud noise (Edoh, 2014).

Cicada are big ugly things. The most famous (and loud) Japanese cicada, kumazemi, measures 7 cm long, about 3 inches long (Holden, 2007). But don’t worry, they are wimps. They can’t bite, they can’t fly well, and they can’t hide. Their only defense is their numbers (Milius, 2013). My old cat loved to chase and eat them. He would get fat from gorging on them during summer swarms. Oh, and the male cicada can get loud. Up to 95 decibels, about the same noise level as a subway train.

Catching cicada is a traditional summer pastime for many Japanese children. Lafcadio Hearn (1900) accounts of how these cicada despair when captured:

The sound made by some kinds of semi (cicada) when caught is really pitiful, — quite as pitiful as the twitter of a terrified bird. One finds it difficult to persuade oneself that the noise is not a voice of anguish, in the human sense of the word “voice,” but the production of a specialized exterior membrane. Recently, upon hearing a captured semi this scream, I became convinced in quite a new way that the stridulatory apparatus of certain insects must not thought of as a kind of musical instrument, but as an organ of speech, and that its utterances are as intimately associated with simple forms of emotions, as are the notes of a bird — the extraordinary difference being that the insect has its vocal chords outside.

Japanese literature teems with cicada. Japan inherited appreciation of the bug from China. The Chinese scholar Riku-un, as he is known in Japan, wrote about the virtues of the cicada (Hearn, 1900):

The Cicada has upon its head certain figures or signs. These present its characters, style, and literature.

It eats nothing belonging to earth, and drinks only dew. This proves its cleanliness, purity, and propriety.

It always appears at a certain fixed time. This proves its fidelity, sincerity, truthfulness.

It will not accept wheat or rice. This proves its probity, uprightness, honesty.

It does not make for itself any nest to live in. This proves its frugality, thrift, economy.

One species of cicada is called higurashi in Japanese which translates to “day-darkening.” This cicada only sings at dusk. The Japanese poet Yokai Yayu wrote: “no matter how many higurashi be singing together, we never find them noisy” (Hearn, 1900). Japanese poets play on the meaning of the cicada’s name, believing the strums of the bug made darkness descend faster:

Oh Higurashi!

even if you let it alone,day darkens fast enough!

And another from the poet Rikei:

Already, Oh Higurashi

your call announces the evening!

Alas, for the passing day, with its duties left undone.

Most Japanese poems about cicada are short and attempt to mimic the sound the insect makes. The 18th century poet Yokai Yayu captures the association of the cicada with summer’s heat:

The chirruping of the cicada

aggravates the heat until I wish

to cut down the pine-tree on which it sings.

Other Japanese poets found the sounds of the cicada as annoying as the summer heat:

Meseems that only I, —

I alone among mortals —

ever suffered such heat!

Oh, the noise of the cicada!

Gone, the shadowing clouds! —

again the shrilling of cicada

rises and slowly swells, —

ever increasing the heat!

Fathomless deepens the heat:

the ceaseless shrilling of cicada

mounts, like a hissing of fire, up to the motionless clouds

According to Hearn (1900), the shells cicadas leave after their final molt are used in both Japan and China as medicine to cure ear-aches. Nice irony!

There are many more poems, but you get the idea. Anime’s association of the cicada with heat pulls from centuries of Japanese literature. The scenes of power lines with cicada chirruping are meant to evoke feelings of summer. As you look at the summer sky and you wipe your brow, this is what you would see and hear throughout most of Japan. I surmise these scenes can make many Japanese anime watchers nostalgic.

Some anime fans speculate power lines represent philosophical concepts like the connection among all things. This may be true in some anime, but most of these scenes provide reflective calm after major events in the story. They establish the feeling of summer. These scenes invoke memories of home and childhood.

References

Baseel, C. (2014). Why does Japan have so many overhead power lines? JapanToday. http://www.japantoday.com/category/lifestyle/view/why-does-japan-have-so-many-overhead-power-lines

Edoh, K., (2014) Modeling Cicada Sound Production and Propagation. Journal of Biological Systems. 22 (4) 617-630.

Hearn, L. (1900) Shadowings. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company.

Holden, C. (2007) Random Samples. Science, New Series. 317 (5843) 1301.

Lewis, L. (2007). Amorous cicadas drown out sound of silence. The Times.

Milius, S. (2013). Mystery in Synchrony: Cicadas’ odd life cycle poses evolutionary conundrums. Science News. 18 (1) 26-28.

Shikibu, Murasaki. The Tale of Genji. N.p.: Tuttle, 2006.