This article will spoil the first episode of Oshi no Ko.

At first glance, Oshi no Ko appears to be another Japanese pop idol anime, but the story quickly bursts that assumption. Ai is a 16-year-old idol who was scouted by a tiny talent agency. So far, so normal. She’s pretty with a unique eye design which plays into a well-handled (okay, amazingly handled) scene late into the theatrical-length first episode. Ai, however, is pregnant and with twins no less!

Let’s pause a moment and discuss Japanese pop idol culture. Japanese pop idols weave a fantasy of availability and virginal appeal to its audience. Part of the fantasy is the idea that you just may have a shot at dating and having a relationship with an idol. However, actual dating is taboo and, as Oshi no Ko discusses, can end a career. The anime doesn’t exaggerate. Getting pregnant as Ai does would be the end of her entertainment career. Because of this, the agency, which is a husband and wife partnership, takes extreme measures to protect her secret.

Ai goes to a rural hospital to have her babies in secret. The story briefly touches on the question of abortion, but Ai wants to have the children. In fact, later she states she purposefully got pregnant because she wanted to experience love without lies involved, and a baby would be the only way she may experience such love. It so happens the rural doctor who takes care of her is a fan. There’s some jokes about his lolicon desires which some of the audience may find off-putting. However, this anime comes from Aka Akasaka, the writer of Kaguya-sama: Love is War. Akasaka writes dialogue layered with subtext. The lolicon jokes surrounding Doctor Gorou Amemiya hide why he became obsessed with Ai. One of the doctor’s young patients was a fan of Ai, and he failed to save that patient’s life. The doctor’s interest with Ai provides a link to this patient, and a way to remind himself of his failure. So when Ai enters his clinic, the doctor vows to make sure her twins are delivered without problems. He views this as a way to vicariously save the patient he failed.

Only Ai’s stalker kills him on the night Ai’s twins are born.

Here Oshi no Ko takes a twist. The doctor and the patient he failed to save are reincarnated as Ai’s twins. Which brings us back to Ai’s reasons for getting pregnant. Ai’s life centers on lies. The story skewers the entertainment industry for creating a fantasy built on lies, and the story lambasts the fandom for their dehumanizing obsession with entertainers. It points to how everyone lives in a manufactured fiction, from the creators to the consumers. But let’s center on Ai. Ai pays the price for this fiction. She becomes so immersed in lies that she lies to herself. Hers is the plight of modern life.

Ai lies to herself: about who she is, what she wants, how her fans effect her, how the Internet effects her, her ability to love, all the way down to who she is. She lies to herself that she enjoys being an idol, that she loves her fans. She even considers her lies to the fans–her love for them–as a true expression of her love. She becomes pregnant in a desperate effort to experience genuine love–not from the father–but from her babies. However, unknown to her, her babies are reincarnated fans.

Her babies, in essence, become one of the lies of her life.

Aquamarine–the doctor–and Ruby–his patient–hide their identities from Ai while working to support her career, not understanding, at first, how her career destroys her for their sake. Throughout the episode, dialogue takes on layers of meaning when you keep this background context in mind. I’m pretty hard-hearted when it comes to stories, but some of the subtext in Ai’s dialogue actually brought a tear to my eye. The pain Ai feels, hidden behind her smile, her starry eyes, and her chirpiness, hit me several times. It’s rare for a story to prick my emotions like that. But if you aren’t paying attention to the underlying threads Akasaka weaves, you can be forgiven for thinking Oshi no Ko only focuses on critiquing the entertainment industry and consumers. You will miss the undercurrents.

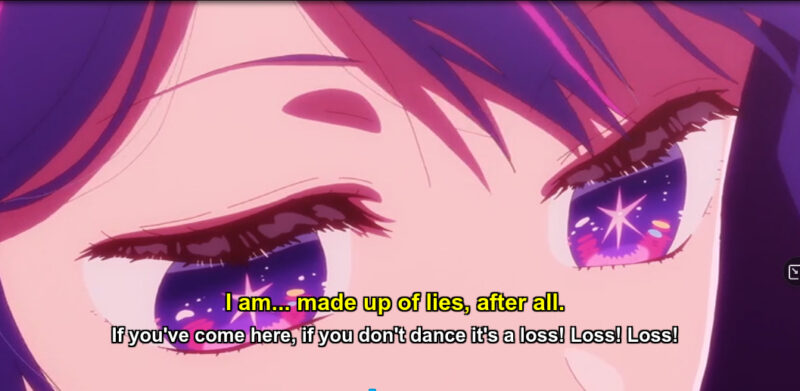

For example, during a performance, we get a look into Ai’s thoughts. In one line she states: “You are the ones who want something almost inhuman.” The line points to how Ai resents how fake she has to be in order to give the fans and the industry what they want. But she also resents herself for becoming inhuman, for losing herself before she could discover herself. Although she is young, she understands something is wrong with her. She then states that she puts on the smile that pleases people the most–but not herself–and she is made up of lies.

Ai’s tangle of lies comes to a head during her death. A stalker–who the story suggests is the twins’ father–stabs her. He is driven by the end of his fantasy once he learns Ai had twins. He felt cheated by how she told the fans–him–“I love you.” The scene is beautifully handled in its ugliness. Ai confesses that she considers herself impure, dirty, and dishonest. Her pent up layers of self-loathing, hidden and suggested under her dialogue throughout the episode, bubbles up. She always hoped the lies of love would become true–the very reason she had her children. Remember, however, that her children are reincarnations of two fans. They love her as both her children and her fans: they embody the lies and the love Ai craves. Ai tells her stalker, “Lies are love,” but even that statement is a lie that Ai desperately needs to believe. She has to believe that her short life had meaning that all her lies were actually loving truths.

She goes on and tells her murderer “Even now, I want to love you.” Let’s unpack this. First, she can’t love him because he killed her and threatened her babies. Yet, she feels the pull of the lie: saying she loves him means she wants to hate him. Wanting to hate him twists back into loving him. This statement, perhaps more than any other of the layered lines Ai says, illustrates her internal tangle.

After the stalker flees, Ai turns to her children. So far, she hasn’t told them she loves them, fearing she would tell the ultimate, final lie if she had. She knows she’s dying. Aqua is doing his best to staunch the bleeding with his 4-year-old body after calling for an ambulance, but he knows he can’t save her. Ruby is trapped on the other side of the door Ai has collapsed against. Ai, knowing she won’t have another chance, risks telling them she loves them. Her relief that the words aren’t a lie, that she finally experienced true love, fills her as she dies.

Her death was well handled by the animators. As the scene plays, you see the stars in her eyes wink out one-by-one until finally, as her relief and love toward her children envelops her, her star-pupils fade. The scene is beautiful and ugly with the final frame of her death underlying just how hideous death is. The sickly tone her vibrant color palette takes on in the harsh light punctuates the scene. Well, just look at these frames.

Ai is 20 when she dies.

After her death, Ruby and Aqua deal with the fallout. Both are enraged by how the fans say hurtful things online and otherwise ignore how Ai’s death hurts real people. Oshi no Ko doesn’t back off from its commentary of how full of trash the Internet and the entertainment industry are. Many fans will feel uncomfortable with the story’s commentary. The idol industry and people’s mixing of fantasy and reality costs Ai her life–the entirety of her life.

Further Thoughts on Episode 1’s Subtext

The problem with subtext is how easy it is to read too much into it. However, Oshi no Ko’s characterization teems with subtext just under its commentary and comedy. Much of the dialogue in the first episode have double and even triple meanings, particularly when you consider the context of the story. Ai’s dialogue has more layers than the other characters in this episode because of her character complexity. Subtext, however, is often missed by people. In some reviews I’ve read about this episode, the writer saw only the surface of the story, which is fine. After watching Kaguya-sama: Love is War, I went into Oshi no Ko expecting subtext, satire, and commentary. In fact, I expected more satire than the first episode has. Both were pleasant surprises. I wasn’t able to predict the direction of the story either, which is fairly rare with anime and other forms of storytelling lately.

Oshi no Ko’s first episode stuck with me. I thought about the episode for over a week before writing this article. Ai’s death scene stuck out in my mind. While I watched it, my inner animator felt impressed with how the frames were handled, the death motifs that appeared, and the quality of the linework. The treatment of Ai’s death, the ugly beauty of it, and how it cast a light backward into her story was well done. When I went back to look at some of Ai previous dialogue, knowing where the episode headed, the subtext of her thoughts and words popped. That’s how subtext works. Subtext becomes apparent in later revisits or when you reflect on a story. When working with subtext, not only is the surface level true–the commentary about the entertainment industry–but also the character level underneath that. Meaning is rarely either-or. Usually, meaning is “all of the above.”

Oshi no Ko’s first episode could stand alone as an example of what animation can achieve. The episode wouldn’t work as a live-action story. Ai’s death is final. Her design won’t show up in another story as an actress would. Live action also couldn’t handle the way the life leaves her eyes nor the shift in her colors as death grips her. Animation, if well done, can capture the way death strips away layers and life better than live-action can. Oshi no Ko’s first episode offers a good study for anyone who wants to learn how to write interesting subtext and a tangled character and the potential animation has for story telling.

I think you also need to mention that it’s not just Akasaka working on this series. The artist is Mengo Yokoyari of Scum’s Wish fame. Her art is perfect for Oshi no Ko.

I’ve been reading the manga for a while now and I’m fascinated at how this look at every sector of the Japanese entertainment industry eventually leads to the truth behind the circumstances of what happens in Vol.1/the first episode.

Thanks for the extra information! I hope the anime is handled carefully so it will follow the manga.

I consider spending more time reading manga. Would you recommend using an e-reader?

The anime staff that did Episode 1 said they loved Volume 1 of the manga and really wanted to make sure that the adaptation did the original source justice. So I will trust them on making sure the anime captures what the manga is trying to tell its readers.

I think using a e-reader is fine since the library apps have that option for manga. There’s also manga apps too. I don’t know if you heard, but Viz Media now has a Viz Manga app with a extensive library of titles (non Shonen Jump and separate from the Shonen Jump app) that spans a variety of genres. https://www.viz.com/vizmanga

Just some observations about the title and name implications when read in Japanese:

Oshi no Ko (推しの子) “Favorite Child”.

Hoshino Ai (星野 アイ) Star-field Love (as in “愛”… except that it’s not. It’s in katakana.) Also, “野アイ” implies “wild eyes”. So “Star Wild Eyes”, and not “love”.

Hoshino Akuamarin (星野 愛久愛海) Note “ai” as the first and third kanji of the given name, which implies a “sea” of “forever” love of a “real” (not merely of the passionate “koi”) variety.

Hoshino Rubii (星野 瑠美衣) “gemstone-beauty-clothing”, seems to imply being hidden under one’s beauty.

Arima Kana (有馬 かな) “Possessing-Horse kana” Possessing a “Horse” spirit is to be social, but perhaps manipulative. Wise and talented, but impatient. However, “Kana-” implies not having anything to say, or perhaps sadness.

Kurokawa Akane (黒川 あかね) “Black-River Red-ne?” I’ll leave it at that.

Saitō Ichigo (斎藤 壱護) “Spiritual-Purification Wisteria” and “Number-One Protector” Wisteria are a symbol of falling in love… a tradition in Kabuki.

Saitō Miyako (斎藤 ミヤコ) “Spiritual-Purification Wisteria” and “Shrine-Child?” The katakana characters leave some mystery to the interpretation of the given name.

Of course, there are more. But just glancing down the list of characters, it’s clear the kanji used (or not used) for their names say something about them. Kana are also used to obscure meanings.Kamiki Hikaru (カミキ ヒカル) has some very interesting possibilities.

And the “Crow Girl”… In Shinto, “Yatagarasu” is a guiding kami sent by the gods, usually represented as three-legged crow.

Thank you for adding more to my subtext argument. The names not only point toward events in the story, but also the layers of personality and conflict within the characters.