Regret acts as the centerpiece for the story. Small regrets sometimes blossom to large–Kakeru’s suicide. But the story shows how every decision–and in the case of Naho, indecision–adds up in ways that can’t be predicted. Regret comes from hurtful outcomes and missed opportunities. However, as the anime shows, missed opportunities can often be beneficial. Orange makes a fuss over Naho’s inaction. She’s hesitant and fades into the background whenever she can. Yet, her letters demand she take the lead when it comes to Kakeru, forcing her to push beyond her usual behavior. Her regrets come from her inaction. I’ve had mild regrets over missed opportunities before I considered what I gained. For example, I didn’t go to prom or date in high school. I was a nose-to-the-grindstone workaholic. Now, many would think I’d have regrets surrounding such decisions. I’ve pondered how things may have turned out otherwise, but I gained most of my computer skills, interest in art, interest in writing, self-awareness, and self-acceptance during this period. I may have gained such by being more social, but I doubt it. My point: regret comes from misplaced expectations and misplaced understanding.

Suwa has the most regret and conflict in the story. He has feelings for Naho and knows from the letters that he marries her. He even has a photo of his future family. However, this happens only if Kakeru dies. He decides to push aside his feelings for Naho in order to save Kakeru’s life. In a few scenes, Suwa wrestles with this and wonders if there is a way to save Kakeru without encouraging Naho’s relationship with him. However, his letter suggests it isn’t possible (as does the letters of his other friends Chino, Hagita, and Murasaka). He hides his pain and feelings behind a smile and takes on an elder brother-like role. As anyone who has tried this knows, it’s difficult to set aside such feelings and encourage your interest to have a relationship with another. Some reviewers have criticized Suwa’s character as unrealistic, but they miss the subtle signs of his pain in various scenes. It’s not easy for him, but he doesn’t want to risk Kakeru’s life.

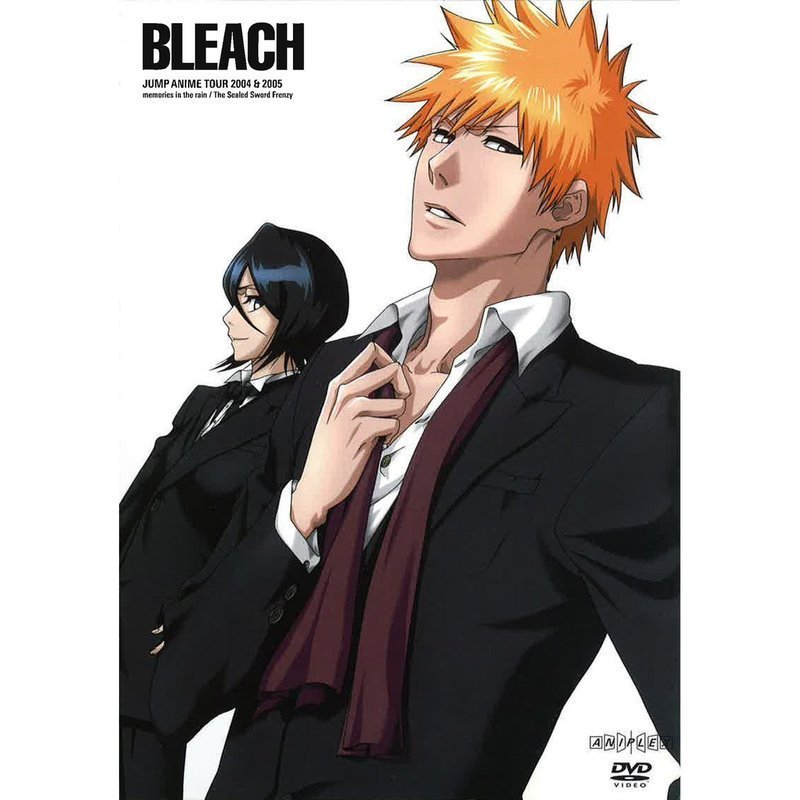

Suwa is an interesting portrayal of masculinity. He’s the standard athlete and desired by the high-school ladies. But he’s sensitive and thoughtful. Of course, Orange is a shojo story. Kakeru, for that matter, is thoughtful. Neither are impulsive as shonen would have them to be. Shojo focuses on feelings and relationships, whereas shonen focuses on action with relationships and feelings mostly sidelined. Suwa is who I wish more shonen protagonists would be–there’s no impulsive behavior or yelling from him. He also doesn’t believe action is the best solution. In several scenes, he steps back and lets Naho fumble her way through. He appears only when she needs support instead of leading the charge. Now, some of this is because she’s the main character, and shojo likes nice, supporting male side characters. But after I’ve watched a series of shonen, his character strikes me as refreshing and seriously needed in male-oriented stories. Suwa is masculine as masculine should be–sensitive, thoughtful, and not impulsive. He’s not selfish, and he’s strong enough to restrain himself. Restraint takes strength most shonen characters, as powerful as they are, lack.

Regret hangs over all of us when a friend or loved one dies. Our minds are keyed to notice the negative, including memories. We think of all the times we wronged or neglected our parents, friends, spouses, and other dear ones. Orange has this running through it too. We take life for granted and assume people will always be there. We assume we have time. Yet, as the Bible states (and all the major religions of the world) life is but a vapor, here and gone without warning. Unlike Orange, we don’t have letters from our future selves to help us. And so we will have regrets. We will make mistakes. We will take people for granted. We will fail to see signs of pain, and some of us will miss signs of suicide. However, regret isn’t negative. It is a natural part of feeling love and compassion.

As for the anime, it isn’t without problems. It goes out of its way to explain how the letters travel through time to an alternative universe. Some reviews I’ve skimmed spoke about how the story’s backpedaling of feelings annoyed them–I found it realistic. Backpedaling is what people do when feelings are difficult. However, Orange is worth a watch if you are interested in the themes I’ve discussed. It is a character driven story that offers lessons shonen stories need to take to heart.

Great insight, thank you for your thoughts!