What makes Neon Genesis Evangelion important? I asked myself this as I researched for this article. The fact the series and movies are still some of the most discussed stories suggests just how much of an impact the anime made in 1995. Yep. The anime is 20 years old and still being talked about.

What makes Neon Genesis Evangelion important? I asked myself this as I researched for this article. The fact the series and movies are still some of the most discussed stories suggests just how much of an impact the anime made in 1995. Yep. The anime is 20 years old and still being talked about.

Okay, I will admit that I don’t like Shinji in the series. He is a little wrist cutter that often made me want him to go up the street and be done with it. However, I enjoy the Rebuild movies. That Shinji, I like. It is rare for me to have such a reaction to a character. That alone told me that Evangelion has something that resonates with people.

No. I won’t be picking apart the endless layers this anime has. Whether you think Evangelion is an overrated mess or a masterpiece, the anime was a seismic shift in storytelling. Otherwise, we still wouldn’t be talking about it.

Evangelion is difficult, to put it mildly. It has layers of symbolism and philosophy. These layers are what make Evangelion the touchstone for any new anime that tries to be densely psychological (Ballus & Torrents, 2014). As I mentioned. I won’t get into the layers. There are many other articles floating around about Evangelion’s philosophy. I am concerned about why the series is important.

There are four major reasons behind the series importance. I will look at each in turn.

Subversive Mecha Storytelling.

Anno Hideaki is a mecha fan (Plata, 2014). His interest in the genre allowed him to turn its tropes inside out. Anno and two of his friends founded Gainax Studios in 1981 and worked on several intellectual films (Redmond, 2007). The experiences led the small studio to create a subversive storyline that changed how we consider mecha and anime in general. Many consider Evangelion’s story to be one of the most subversive in film. Evangelion is also thought to revive interest in both anime and mecha during the 1990s. (Napier, 2002;’ Redmond, 2007).

Evangelion begins by playing on what people think of as mecha. Big robots, teen heroes, fan service, and similar conventions and references to mecha shows before (Ballus and Torrents, 2014). Then, Anno breaks them apart.

Typically, mecha refight some type of World War II scenario where Japan gets to win. There are tyrants and evil aliens to shoot with giant robots! And of course these tyrants and aliens often represent ideas like consumerism, neonationalism. and other -isms that came out of World War II. Anno plays this up by naming characters after warships from World War II – Langley, Akagi, Ayanami and Katsuragi (Redmond, 2007; Plata, 2014).

Even the bikini clad fan service shots of mecha women reference World War II’s influence. The bikini was designed in honor of Bikini Atoll – the third atomic attack on Japan. In 1954, the US tested a hydrogen bomb on the atoll. The bomb blew up, and the fallout landed on the Japanese fishing ship called The Lucky Dragon. Several crew members died. The incident inspired the famous monster movie Godzilla and become a stable in skimpy female fanservice ever since (Redmond, 2007).

Well, anyway. those of use who watched Gundam and other mecha know the male hero is an idealistic go-getter. Sometimes a little reluctant, but he steps up in the end of his own accord. Shinji is everything but that.

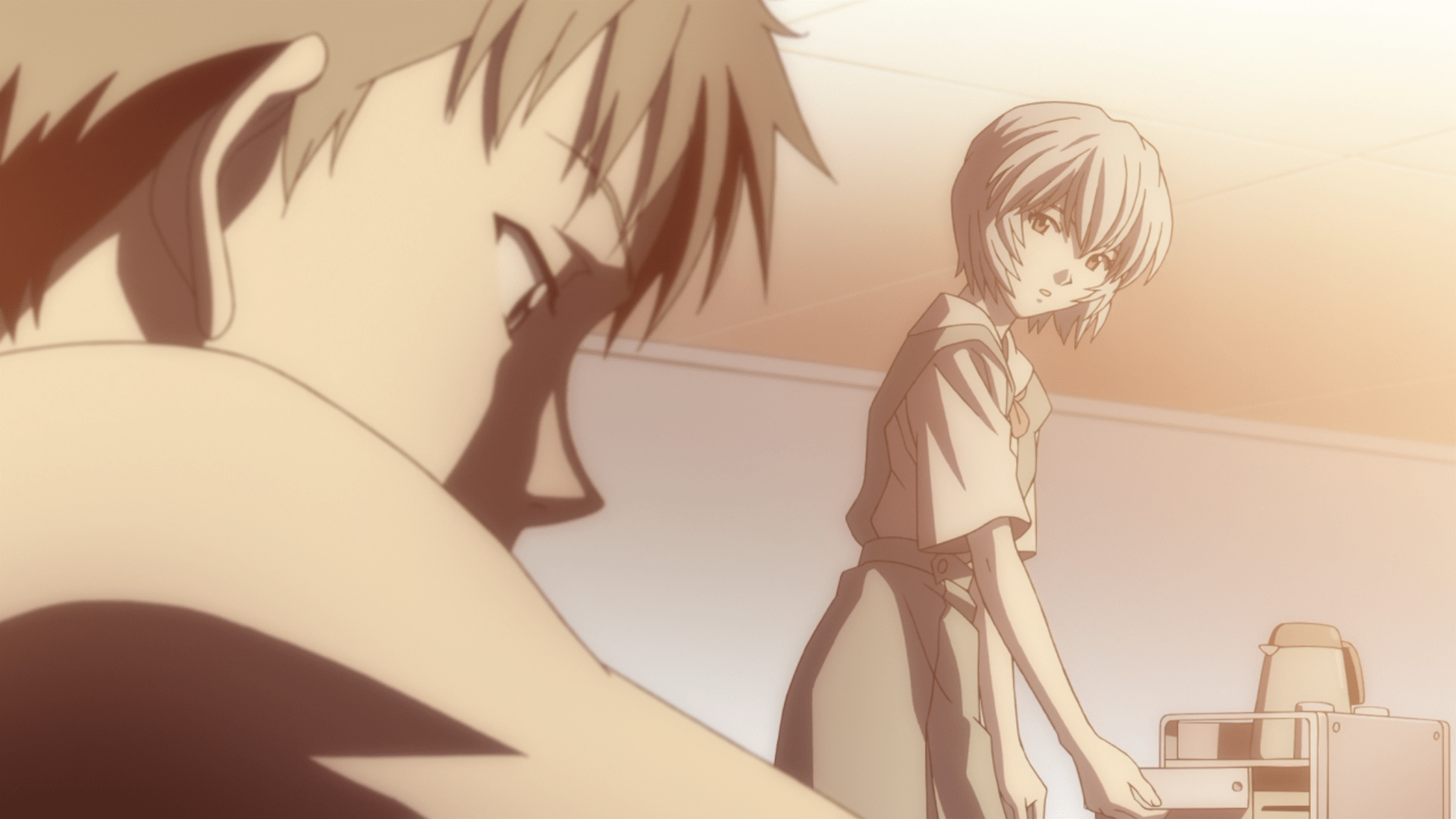

The characters in Evangelion are messed up. Sure, many other mecha characters were too, but not on the same level as these children. The hero, Shinji, is a hikikomori that with obsessive compulsive disorder. He plays tracks 25 and 26 endlessly to shut out the world (Plata, 2014). Asuka Langley is just as messed up as Shinji (perhaps more so) but shows it differently. She places her entire sense of self on her abilities to pilot an EVA; to be useful for adults.

The characters in Evangelion are messed up. Sure, many other mecha characters were too, but not on the same level as these children. The hero, Shinji, is a hikikomori that with obsessive compulsive disorder. He plays tracks 25 and 26 endlessly to shut out the world (Plata, 2014). Asuka Langley is just as messed up as Shinji (perhaps more so) but shows it differently. She places her entire sense of self on her abilities to pilot an EVA; to be useful for adults.

Shinji is depressed, naive, and shut off. A far cry from the typical mecha hero. That is why he annoys me so much. He grows up only in tiny increments. I expect a hero to grow into adulthood and his role. Shinji does neither. That is a twist on storytelling that shatters typical idea of how a hero should be. Certainly, there were other heroes similar to Shinji before Evangelion, but Shinji is a focused study of a distressed mind. It is quite different from the usual go-get-em hero.

Visual Impact

Neon Genesis Evangelion set new visual standards for the time. Gainax integrated CGI with hand-drawn cel animation. While we consider that normal nowadays, it was a new idea in the 1990s (Redmond, 2007). The series also used framing techniques more commonly seen in Hollywood than in anime.

[Warning: mild spoilers]

The final episodes of the series deserve a mention here. Neon Genesis Evangelion is known in Japan as Shinseiki Evangelion. This translates to “Gospel of the New Century” (Redmond, 2007). The final two episodes, along with the turnabout on the mecha genre makes the Japanese title apt.

The visuals of the final episodes are striking, and completely change how we think of a finale. Mecha is known for its extravagant final fight scenes. I’ve watched some amazing last fights. Evangelion has nothing of it. The final episodes delve into the tortured psyches of the characters. Instead of explosions and giant robots we see photo montages, stick figures, and blank scenes set to Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” (Napier, 2002).

Many blame the lack of visuals and combat in the final episodes on a lack of budget. However, this is not true. Gainax released lavishly animated film The End of Evangelion immediately after Evangelion ended. What Anno did in the final episodes finished the deconstruction he wanted. The finale being a trip into the psyche broke new ground. No one did anything like it, and that was why so many fans felt discontent and thought money was a factor. Rather, the episodes are a raw look at the “apocalyptic psyche,” the mind of a person who must face all the desperation and insecurities of being human without a giant robot to blunt the trauma (Napier, 2002).

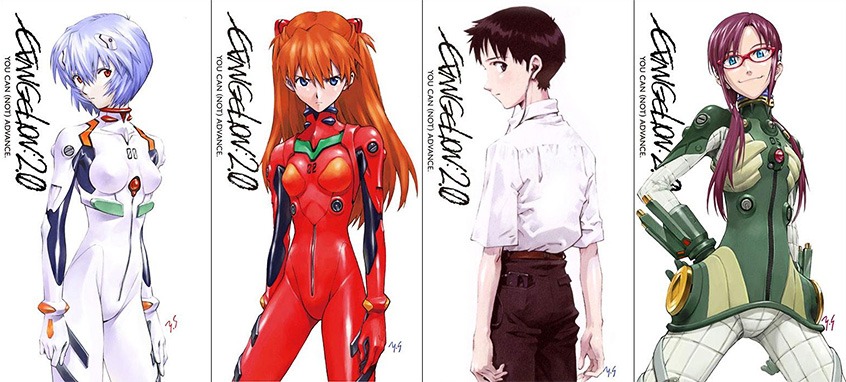

Strong Female Protagonists

Many anime from the 1980s featured strong female characters such as Bubble Gum Crisis, but Evangelion has more powerful and self-aware female characters than any anime before it (Redmond, 2007). Misato Katsuragi suffers from the trauma of her father’s death and living in an apocalyptic world. She has moments of weakness, but she does not need saved by a man. Asuka is traumatized and messed up, but she is no damsel in distress.

It is common for anime to take strong female leads and make them into a voyeuristic object for the male audience. Mecha does this as well. Anno takes even this common fan service and subverts it to tell a story and strengthen his female characters. Take episode 12. We see Misato’s memories of childhood. The first impact and the death of her father. The scene cuts to Misato dressing in front of a mirror. Boobies! Not quite. The scene emphasizes what she lived through more than it emphasizes her sexuality. Anno takes the tired fan service and shifts it to illustrate what the women have gone through or to provide an unsettling contrast to the slow psychological problems that accumulate (Redmond, 2007; Plata 2014).

The End (Beginning) of Mecha

Evangelion breaks the mold of the mecha genre. Although, it is hard for us to see that now. So many anime reference Evangelion that its fresh take on the mecha hero and psychology is now tired and a trope. All tropes were once a new idea. However, the fact we still talk about it 20 years after the fact shows us just how influential the series is. Evangelion’s visuals and stark visual representation of the mind broke new ground. The lack of an extravagant finale still bothers many fans. Its female protongists and use of fanservice to prove a point is rarely seen up until Kill la Kill.

Evangelion marked the end of mecha, and a beginning. It changed how people think of mecha and other anime. The layers of symbolism, the exploration of human insecurities, and the examination of human identity make this a dense, difficult story that will continue to resonate and inspire.

References

Ballus, A. & Torrents, A. (2014). Evangelion as Second Impact: Forever Changing That Which Never Was. Mechademia, 9283-293.

Plata, L. (2014). The Crisis of the Self in Neon Genesis Evangelion. Kinema Club Conferences for Film and Moving Images. Harvard University.

Napier, S. (2002). When the Machines Stop: Fantasy, Reality, and Terminal Identity in “Neon Genesis Evangelion” and “Serials Experiment Lain.” Science Fictions Studies. 29:3.

Redmond, D. (2007) Anime and East Asian Culture: Neon Genesis Evangelion. Quarterly Review of Film and Video. 24:2 183-188.

I do agree in that Evangelion is a very influential anime, as evidenced of its immense popularity that still thrives.

That being said, I would like to point out two mecha anime, both from the same director, that was influential in changing the mecha genre: Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) and Space Runaway Ideon (1980), both by Yoshiyuki Tomino. The very first Gundam series was the first series to decontruct the “hot-blooded, gung-ho, all heroic boy hero” of mecha anime.

Let’s start with Gundam: main character Amuro Ray was not your typical protagonist; resistant to fight, cowardly, whines, and has to be set straight constantly from the supporting cast (this is where the infamous “Bright-slap” originated among fans). The very first Gundam hero was an idealistic at all, in fact was rather pessimistic! Shinji is rather the more exaggerated version of him.

The story itself was also not typical of Japanese good guys over evil demonic or alien invaders, but against other humans, and with a more gray and gray morality. See, Gundam is not about good vs. evil, but of the perils and consequences of war. The Earth Deferation and Principality of Zeon were neither the good guys nor bad guys, both factions had their share of corruption, ambitious leaders, and shady war practices. Although the “good side” Earth Federation still won, they would show their full-blown corrupt side in the sequel Z Gundam. On the Zeon side you had Char Aznable, the rival who was not fighting for the sake of his country, but rather to kill them from within as a very long plot to avenge his family.

This series was the first deconstruction of Giant Robots, and introduced the concept of Real Robots (mass produced, not all powerful, military use, easily damaged, no gimmickly attacks like rocket punches)

Space Runaway Ideon is another series worth noting. Anno himself said that this series was an direct inspiration for Evangelion itself. This series showed the absolute doomsday scenario and consequences of having godlike capabilities and its use. Read more about it here: http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Anime/SpaceRunawayIdeon

Gundam was the first deconstruction, or the one of the 80’s, and Evangelion was the deconstruction of the 90’s. For 2000’s and higher, to me Code Geass and Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann are ones worth of turing the mecha genre on its head. I could go on more but the main point was to make aware of two mecha anime that have influenced and changed mecha anime throughout anime history.

Thanks for the additional information! Like most story genre, each decade and generation leaves its own touch on it. Mobile Suit Gundam is certainly influential. Evangelion continues to capture people’s interest and imagination. I am more familiar with Evangelion than Gundam and see Evangelion discussed more often than the Gundam series. Granted, Gundam is incredibly popular, but for many reasons Evangelion continues to resonate more with people. That isn’t to diminish Gundam. Different stories resonate with different people and time frames. Genres need to be deconstructed and rebuilt regularly in order to remain relevant with the concerns of the current time period.

Thanks again for the great comment!

Editor’s note: The original comment contained an entire blog post about Evangelion. I removed the copy and paste and provided a link to the article instead.

See this article for more information regarding Rebuilding Evangelion.

Thanks for the additional information!

“I don’t see any adults here in Japan. The fact that you see salarymen reading manga and pornography on the trains and being unafraid, unashamed or anything, is something you wouldn’t have seen 30 years ago, with people who grew up under a different system of government. They would have been far too embarrassed to open a book of cartoons or dirty pictures on a train. But that’s what we have now in Japan. We are a country of children.” – Hideaki Anno

I find this quote of Anno’s interested. I’ve read about this view of Japanese men (and even American anime fans) before. Many worry that popular culture is undermining the meaning of traditional adulthood.