One among many orientalist[i] stereotypes of Asians is that they are masters of imitation (or adaptation) but lack original creativity (or invention); an assumption which looks ridiculous when one spends just a little time studying any given Asian culture, I would say. Rather, I spot the tendency to imitate (instead of inventing) in modern popular culture (of any country). And I ask myself: Is the idea behind this that nothing is so easily, quickly and cheaply made and so sure to sell as something the audience already knows and enjoys? So, why create something new when you can just adapt something known?

Of cause, in practice, it‘s not so simple. According to the Cambridge Dictionary Online, an ‚’adaption‘ is either ‘the process of changing to suit different conditions’ or ‘a film, book, play, etc. that has been made from another film, book, play, etc‘.[ii] In other words, ‘adaptation’ signifies either a general process of transformation, or the specific result of such a process in the area of modern media. I will consider the first for a bit before going into the detailed consideration of some examples of the second.

The Long History of Adaptation

Japan has been ‘adapting’ cultural practice and information for centuries, most notably perhaps Buddhism, which reached the archipelago via China and Korea and became an integral part of Japanese spiritual life, branching out into various indigenous schools. The form of Buddhism Japan is most known for in the west, Zen, originated in China but was, in common opinion, completed in Japan. Subsequently it has strongly influenced the ‘way’-based arts from budō (warrior arts: karate, jūdō, kendo, etc.) to shodō (calligraphy) to sadō (the tea ceremony).

Along with Buddhism, writing in Chinese characters came to Japan, and they made possible an influx of Chinese ideas from poetry and philosophy to popular culture. Similarly, from the first encounters in the sixteenth century Western technology and knowledge began trickling into Japanese culture, until the Meiji Restauration 1868 started a metaphorical torrent of ‘Westernization’. What’s interesting about these broad historical processes is that even if they were, for a long part, attempts to replicate the ‘foreign’ concept as closely as possible, sooner or later a hybrid form developed as the result of ‘changing to suit different [i.e. Japanese] conditions’. In writing, the Japanese developed the two kana syllabaries to suit the flexion of their language. In poetry and philosophy, Japanese styles and concepts rivalled with Chinese ones or were synthesized with them. Western technology was and is applied to Japanese issues, from firing Western guns at rebelling samurai in the Seinan War (or Satsuma Rebellion) 1877, to the construction of the multifunctional Western-style bidet toilet, with in-built Otohime, in our day.

To my mind, this far-reaching adaptation is not a negation of original, creative and inventive thought, but the proof of it. I will try to demonstrate this by looking at pop culture, since that is, as you might have noticed, my field of interest.

Jiraiya, the Toad Ninja

A long time ago in Song-era China, there was a thief known as 自来也 , because every time he broke into someone’s

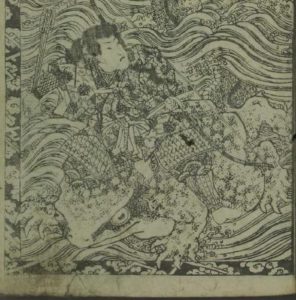

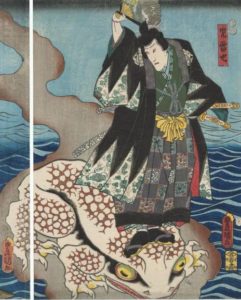

house, he left this graffito on the wall, which basically said ‘I was here‘. The Japanese reading, incidentally, is ‘Jiraiya‘. His story was first told in Japan in a popular novel by Edo-period writer Kantei Onitaka in 1806 and served as a basis for the fantastic story of ‘another’ Jiraiya, now written ‘児雷也‘ (Young Thunder). In the Jiraiya Gōketsu Monogatari, The Tale of Gallant Jiraiya, he is the son of a samurai family fallen to intrigue, who learns toad magic from a hermit to fight his foes, a snake-magic using villian named Orochimaru among them, aided by snail-magic-wielding princess Tsunade. The novel was illustrated by well-known woodblock artist Kunisada, with images so iconic they informed the design of the kabuki stage adaptation of the work.[iii] This performance, in turn, provided the basis for colour woodblock prints of the actors in these roles, comparable to a modern movie poster.

In other words, the story and its title character were adapted from Chinese legend to novel to illustrated literature (a potential manga precursor?) to kabuki theatre, to popular art. Characters based on Jiraiya the toad-magician-ninja have come up in Japanese pop culture time and again, to the present day – most well known is probably his ‘pervy sage’ incarnation in the Naruto franchise.

Modern ‘Media Mix’-Society

Speaking of franchises. A great number of today’s anime are themselves adaptations of manga or light novels, and they in turn inspire games, movies, and even more novels or manga – from fanfiction/dōjinshi to fully commercialized spin-off series (One Piece’s Chopperman and Naruto’s Rock Lee, both comedy manga, come to mind). The simultaneous advertising of different incarnations of the same characters and plot has been called ‘Media Mix’ – it is very noticeable in the well-known Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine, for example, where movies, anime and other products related to the manga series are advertised between chapters. There are a great many examples, both successes and failures, of a story changing format over the years, one of which I will look at later.

Alternatively, stories are remade in the same or a different form, as we know from western comic books and movies. A special example of this dynamic is the

children’s anime GeGeGe no Kitarō, based on a 1960s monster manga by legend(ary) writer Mizuki Shigeru, which has seen a new incarnation, with the same characters and similar plots, in almost every decade. The title sequence alone shows how the series was updated time and again, from the uncanny old voice and black- and white animation of the first series to the electric sound of the 80s, to the ‘sexy teenage idol’ makeover in the 2007 live action movie.[iv] Kitarō in the last version, portrayed by half-Japanese actor Wentz Eiji, looks quite different to his animation precursors, but his silver hair is the call-back to the character’s very first manga appearances – which makes it hard to decide, of cause, which is the ‘original’ text being adapted. By the way, with all the intertextuality, genre conventions, tropes, audience pandering and suchlike going on, you’d have a hard time finding an ‘original’ to many a popular anime anyways…

The Live Action Dilemma

Manga/Anime-to-movie adaptation is a big topic, of cause. Live-action movies have the potential to leave a really big impact – they can be amazing and epic, such as the Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings films (that is not to say these are flawless). A good adaptation captures the spirit of the source material while giving it a new turn in a new medium. Ideally, it can both be appreciated by fans of the original and function as a gateway to new audiences. Some Western-produced anime-to-live-action-adaptations, however, have failed on both accounts, being badly planned, badly written, badly acted catastrophes, such as the infamous Last Airbender[v] and Dragonball movies. This seems to have played a major part in the genesis of the ‘Hollywood can’t do anime’ prejudice. It may come as a surprise to the adherents of this theory, however, to hear that a quite close adaptation of the Rurōni Kenshin (Samurai X) manga to a live-action movie in 2012 (with 2 sequels in 2014) was produced by none other than Warner Bros.

Nobuhiro Watsuki’s Rurōni Kenshin was first published in Weekly Shōnen Jump, 1994-9, and was adapted into a long-running anime series, several OVAs, and (in 2016) even a Takarazuka women’s musical. The plot revolves about travelling swordsman in the early years of the Meiji era, Himura Kenshin. He fights for those in need with his reverse-bladed sword, in order to atone for the numerous assassinations he had performed as a member of the imperial loyalists in order to bring the feudal military rule of the Edo government to a close. In other words, the story is set within the complex historical events of the late 19th century in Japan, and its main character, however good-natured and cute his day-to-day personality, has committed murder countless times. Despite his vow never to do so again, driven to revert to his old self more than once, though he indeed never kills again. In a manga, it is possible to combine such complex ethical questions of atonement, the structure of the human psyche and the working through of traumas with light-hearted slapstick comedy, or to unite precise historical circumstances with flashy costumes and weaponry, but in a live-action movie, this could seem disrespectful or nonsensical. So how did the film crew go about this?

The Strength of Kenshin

In a first, thankful decision, director and cast were kept Japanese, preserving the historical feeling of the manga. Director Ōtomo Keishi

had previously worked for NHK to produce period dramas such as Ryōmaden, where some of the later Kenshin actors appeared as well. Thus the production team is historically and culturally grounded, and therefore able to treat the source material with the appropriate know-how. Art film director Hoshino Keiko even suspects that the long wait (13 years since the end of the manga) for a live action adaptation happened because until Satō Takeru, there was no actor able to perform the lead role.[vi] In contrast, both the Dragonball and the Last Airbender movie disrespectfully changed the ethnicity of the main characters, which angered fans and made the cultural context of the story seem paradox. For example, how come Katara and Sokka in the movie are two white kids, but their clan remains an Inuit-style tribe? Rurōni Kenshin does make some changes to its characters, but not in such a nonsensical way.

Instead, two to three manga antagonists are combined in one character, and the same goes for storylines, a smart move to combine many good scenes from several volumes of manga in a single two-hour film. Apart from the introductory text, all relevant background information is given by characters in dialogue, so it doesn’t feel forced. Furthermore, while the film re-shuffles lot of incidents and plot elements from the manga, they are still the backbone of the plot (pleasing the fans), and the resulting narrative is coherent and logical (so that those new to the story are able to follow).

The comedic tone of many of the manga’s scenes surfaces several times in the film, mainly through the music, which sets the mood brilliantly. For example, it aids the establishment of Takeda Kanryū as the cruel and threatening, yet also ridiculous main villain. Some of the comedic elements in the characters of Kaoru, Yahiko and Sanosuke are also incorporated, most memorably the scene where Sanosuke interrupts a fistfight he is having in a kitchen to share a meal with his adversary, or the misunderstanding-ridden, slapstick-y first meeting between Kenshin and Kaoru, which is highly reminiscent of the source material.

The two most overt changes regarding characters are the transformation of Takani Megumi and the exclusion of Shinomori Aoshi. In the manga, Megumi is a clever, perhaps even sly, woman (often compared to a fox) who makes informed choices; in the film, she appears more like a traumatized girl. Whether this has been done to accentuate Kaoru as the more reasonable female character, or for the sake of casting another young and popular actress, or for an altogether different reason, I cannot say.

Likewise, there are several possible reasons why Shinomori Aoshi was cut from the plot. With so many iconic characters already featured, he might just have been too much of a distraction, but more importantly, there can only be one climax to the movie, and in the Rurōni Kenshin movie, this is clearly the fight between former assassin Kenshin and still-assassin Jin’e. A true-to-manga portrayal of Kenshin and Aoishi’s suspenseful duel would simply not have fit into the storyline. Jin’e also was an adversary Kenshin had great trouble defeating, but more than that, the emotional stakes were much higher, making for the more interesting scene – which is probably why, for the film, Jin’e was included in the Kanryū-plot in the first place. Moreover, the popular character Saitō Hajime play a minor but important role in the movie despite not appearing in the manga until much later. Between Saitōs aloofness and Jin’e’s ability, Aoshi would have felt redundant – though for Aoshi fans, this may have felt like stuffing in Saitō to the detriment of Aoshi.[vii] While some elements of Aoshi’s character have been transferred to the film-version of Hanya, like his mild concern for Megumi and his very fast short-sword-technique, this only leads to further changes, since it creates a character (now names Gein) who is quite different in personality and looks (model with a burn scar rather than hideously disfigured ninja) to the source material’s Hanya.

In the end, though, Rurōni Kenshin is an example for a successful adaptation despite these minor issues. The original manga has been treated respectfully. While its feel and atmosphere, characters and plot, visuals and emotional stakes are transformed as to leave lasting impact on the big screen, they survive this, for the most part, without losing their essence. Again, this evidences a transfer process impossible without clever creative thought.

I might come back in summer to the topic of adaptation and transfer/transformation, and discuss a different example, one befitting the time of year when scary tales are told to induce pleasant shudders against the heat – the cultural impact of O-Iwa, the female avenging ghost. But until then, I close my musings on the topic. Thanks for reading!

Notes and References

[i] The concept of orientalism – the construction of the ‘orient(al)‘ as binary Other to the ‘west(erner)‘, and how it informs discourse on the subject of anything ‘oriental‘ – was developed by Edward Said in his eponymous book (1978). See this website. If you’re short on time, here’s the wikipedia entry.

[ii] http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/adaptation.

[iii] I compiled this information from various dictionaries on kabuki, such as Samuel L. Leiter’s New Kabuki Encyclopedia and its Japanese source, the Kabuki jiten, as well as Engeki hyakka daijiten (Great Encyclopedia of Drama), Kabuki tōjō jinbutsu jiten (Dictionary of Kabuki Characters); and the Koten bungaku daijiten (Great Dictionary of Classical Literature).

[iv] 60s intro https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9boVDep-diw, 80s intro https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9bwOON3-1bY , movie trailer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pX08cqhv0Kg . The animated series itself addresses this in the 40th anniversary special episode, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=64BK6EQW3Qo

[v] I am aware that Avatar The Last Airbender is not a Japanese production and thus not an anime in the literal sense. But its look, cast and atmosphere are paying massive tribute to Asian culture and anime storytelling.

[vi] Katsura, Chiho; Hoshino, Keiko & Urazaki, Hiromi: „Katsura Chiho no eigakan he ikō. Tsukurite-tachi no eiga-hyō [Let’s go to Katsura Chiho’s Cinema. Film criticsm by those who make them“. In: Shinario, 68.11, 2012, 52-68, p. 62.

[vii] Shinomori Aoshi IS featured in the following films (Kyoto Inferno and The Legend Ends), however.