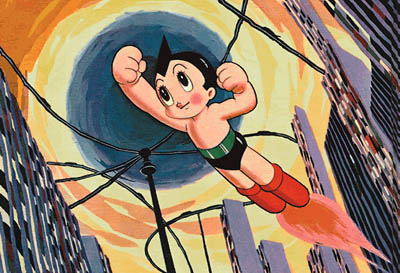

Any series that looks at the most influential anime must talk about Osamu Tezuka’s Mighty Atom (Tetsuwan Atomu) or Astro Boy as we in the West know it. Astro Boy laid the groundwork for anime and manga storytelling, production, and all other aspects of the medium. While it was not the first Japanese animation, Tetsuwan Atomu was the first anime and manga as we think of them.

Any series that looks at the most influential anime must talk about Osamu Tezuka’s Mighty Atom (Tetsuwan Atomu) or Astro Boy as we in the West know it. Astro Boy laid the groundwork for anime and manga storytelling, production, and all other aspects of the medium. While it was not the first Japanese animation, Tetsuwan Atomu was the first anime and manga as we think of them.

Many trees have died to discuss the relationship between Astro Boy and post World War II nuclear concerns. Tezuka creates a utopia that harnesses nuclear power for good. Astro Boy is quite optimistic (Gibson, 2012; Gibson, 2013). But, we are not really concerned about what Astro Boy reveals about the concerns of the start of the atomic age. Although, Tezuka’s commentary is important, my focus in this article is how his work changed the face of anime and manga.

Tezuka, like many of Japan’s first animators, admired Disney animation and American comics. As a child he spent a lot of time tracing – yes, Tezuka traced – George McManus’s Bringing up Father comic strips. His design for Atom (or Astro as we know him) was also influenced by Max Fleisher, the creator of Betty Boop. However, Tezuka studied Japanese artists in addition to Disney, McManus, and Fleisher. Anime was born from Tezuka’s merging of American and Japanese art styles (Napier, 2005 ; Schodt, 2013).

Tezuka also popularized long, cinematic story manga we know today (Schodt, 2013).

What did Tezuka’s merging of American and Japanese comic art actually do? He developed a streamlined style of character drawing that leveraged ellipses, similar to Disney’s style. This allowed Tezuka to draw faster and develop longer stories. This was essentially when Mighty Atom crossed from the page to television. However, this drawing style wasn’t new to America. In fact, Tezuka states his design for Atom pulled heavily from both Mighty Mouse and Mickey Mouse (Schodt, 2013).

Tezuka desired to be the on the cutting edge of manga, and he struggled with this desire his entire life. He often changed his artistic style to match what was in demand. He also wanted to create classics that continued to be read long after the current manga style’s popularity faded (Ito, 2011).

This faster drawing style laid the groundwork for anime and manga art. It allowed Tezuka and later artists to quickly build simple and complex characters with consistency. Have you tried to draw the same character in different poses? It isn’t easy. More complexity creates more room for error. Not to mention it is difficult to make the character look correct from every angle. That is why Disney, Fleisher, and Tezuka focuses on ellipses as the base for building characters. These shapes are easier to manipulate in space. This allows greater speed and fewer errors when drawing a character hundreds of times.

The Most Important Year

In 1963, everything changed. Mighty Atom become Japan’s first animated television series.

In 1963, everything changed. Mighty Atom become Japan’s first animated television series.

Before television and Mighty Atom, Tezuka focused on long manga stories arcs spanning hundreds and perhaps thousands of pages. Mighty Atom and television’s demanding pace of 52 episodes each year. The TV series quickly ate all of the manga’s content, forcing Tezuka to improvise on situations and scenarios (Schodt, 2013). Yes, even the first anime had “filler” episodes.

However, this first time serialization of a manga for television tied manga and television together through episodic, long running plots (Napier, 2005). This is why the word manga (まんが) in Japan refers to both animation and comics.

Mighty Atom ran for only 3 years in Japan despite its popularity. NBC bought the rights to it, and the newly renamed (and censored) Astro Boy was the first Japanese television series to broadcast in the United States (Gibson, 2013).

Much of the problems anime has with pacing can be traced to Mighty Atom. First, Tezuka’s streamlined drawing style, while productive, resulted in lower quality animation. The demanding weekly episode schedule also devoured the manga’s original story. It took Tezuka far longer to produce manga than it did to produce the television episodes. We see this today. The end result is lurching, rushed story arcs that make little sense. Endlessly serialized stories like One Piece and Bleach are victims of their own success. Their storytelling suffers.

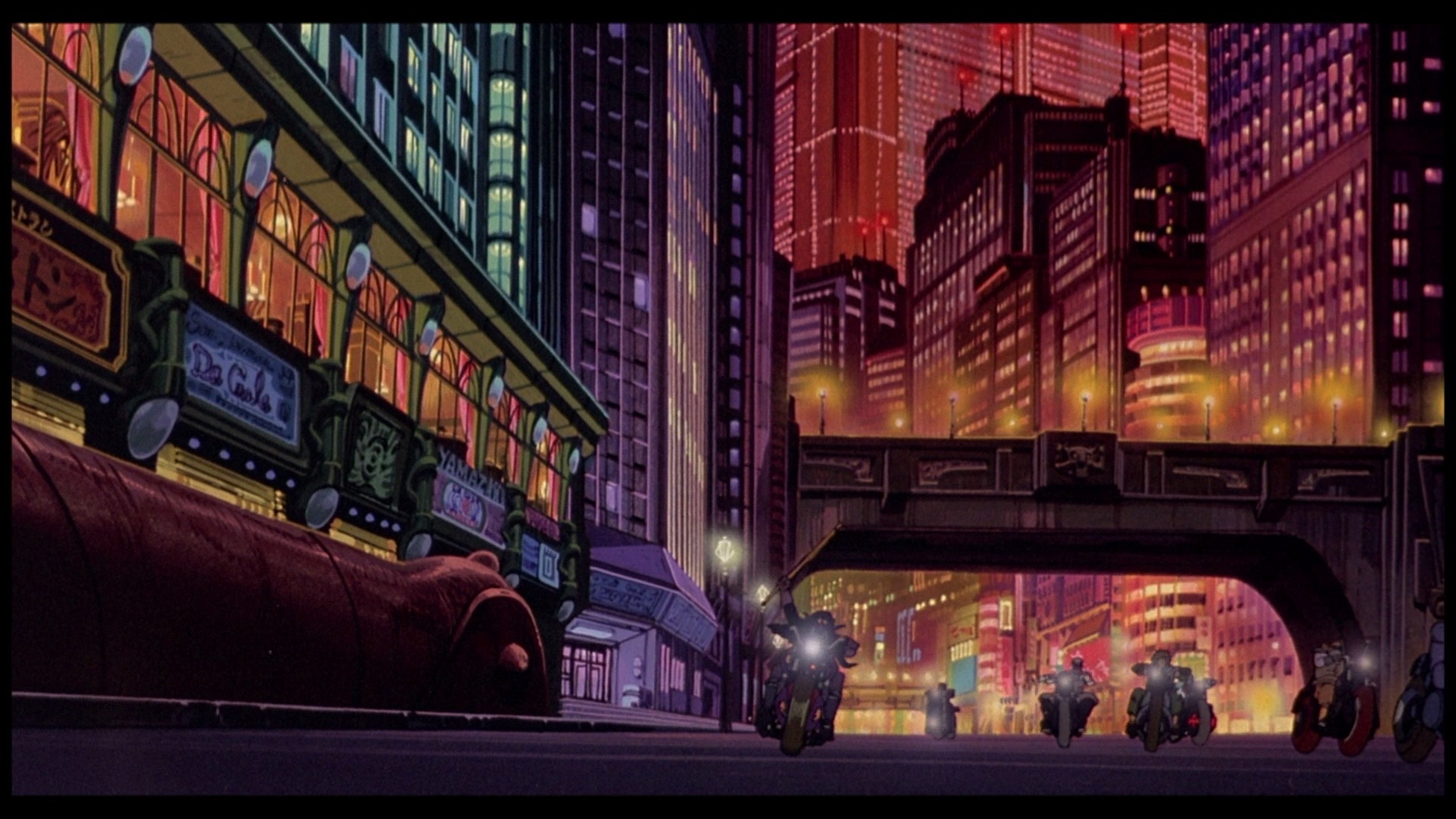

Of course, this doesn’t have to happen. Many set length anime like Eureka Seven, Cowboy Bebop, Samurai Champloo, Space Dandy, and many others do not suffer from the same story problems as serialized shows. However, if even the very first anime had problems with television production, anime may well be at its best when it is not serialized and instead has a set number of episodes.

Tezuka’s Production System

It is a bit of an understatement to say Tezuka was busy. He was so busy, that his health started to decline (Schodt, 2013). In order to keep up with the demands of publishers – Which he could never meet. Tezuka had a bad habit of trying to please everyone – he developed a production system.

It is a bit of an understatement to say Tezuka was busy. He was so busy, that his health started to decline (Schodt, 2013). In order to keep up with the demands of publishers – Which he could never meet. Tezuka had a bad habit of trying to please everyone – he developed a production system.

Tezuka hired young artists to help him with mundane drawing tasks, like inking black spaces and drawing frames. He retained control of his assistants and still did most of the pencil drawing and inking. Together, he and his assistants could produce around 300-400 pages of manga each month. Also, many of his assistants gained drawing and production skills that would move on and become major mangaka in their own right (Schodt, 2013).

Tezuka’s production system is still used by many mangaka today. While not all mangaka shoulder as much work as Tezuka, the production system is unique compared to American comics. In American comic systems assembly line production schemes are often used. There is an inker, a colorist, a letterer, and other -ers that only do that one job. Assistants in manga studios have to be able to do it all, just as they would as a mangaka. Being Tezuka’s assistant also gave these upcoming artists access to publishers and Tezuka’s other contacts.

Pushing Manga Forward

Tezuka is a giant in the world of manga. He is the father of the medium as we know it today. Mighty Atom was the first serialized animated television show in Japan and the first Japanese television show to air in the United States. He merged American and Japanese art styles in a way that continues to inspire. He developed drawing and production techniques still used today.

He also leaves a legacy of problems in the medium: episodic storytelling that is sometimes disjointed, filler arcs, and poor animation. In his defense, I will say that Tezuka and his animation studio were breaking new ground in Japan. The animation is not that bad, but it was lower budget than what Disney could produce.

Tezuka’s influence on manga and storytelling can fill (and does fill) books. Mighty Atom encapsulates concerns about the future and nuclear power even as it forges a new popular medium in Japan. Mighty Atom appeared just as Japanese film production peaked and began in Japan (Napier, 2005). The series found fertile ground and forever impressed animation into Japanese culture.

References

Ito, K. (2011). Osamu Tezuka: His Life, Works and Contributions to the History of Modern Japanese Comics. International Journal of Comic Art. 13 (2).

Gibson, A. (2012). Atomic Pop! Astro Boy, the Dialectic of Enlightenment and Machinic Modes of Being. Cultural Critique (80). 183.

Gibson, A. (2013). Out of Death, an Atomic Consecration to Life: Astro Boy and Hiroshima’s Long Shadow. Mechademia, 8313-320.

Napier, S. (2005). Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. Macmillian.

Schodt, F. L. (2013). Designing a World. Mechademia, (1), 228.