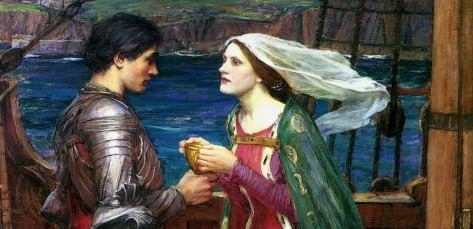

Romantic literature traces to 12th-century France. The first romance story appears to be Tristan and Iseult. As the story goes, Iseult has been arranged to marry King Mark, Tristan’s uncle.

After the marriage they continue their affair (making a suicide pact) until Tristan is discovered and banished. They flee together for three years before they agree Iseult should return to King Mark. Tristan leaves the country and marries a woman in Brittany also named Iseult, but they don’t consummate the marriage. He is wounded in a battle and summons the first Iseult. She arrives after he dies. She dies of a broken heart (Umland, 2001).

The story provides a framework for other romance stories: the love triangle, taboo breaking, secrets, and transgressive yearnings. The framework appears in Japanese love stories too.

Fast forward to modern Japan and to a culture where marriage and romantic love (tragic and otherwise) has become rarer. In the mid-1990s, 1 in 20 women weren’t married by the time they turned 50. By 2015, 1 in 7 remained unmarried. People aged 35-39 who have never married sits at 25%, compared to 10% in the 1990s. Despite this change, single women older than 25 are still known as “Christmas cake,” a reference to old pastries sold after December 25 (Rich, 2019). This was the most recent survey that I could find.

Singlehood represents liberation now (Rich, 2019):

“It’s not fair for women to have to be stuck in their homes as housewives,” Ms. Shirota said. “They are happy as long as they are with their kids, but some of them just describe their husbands as a big baby. They don’t really like having to take care of their husbands.”

Yet people still desire romance and relationships despite the liberation of singlehood. In Japan, romantic love is an “additional something” tied to a good fate. Men and women seek companionship, but it tends to be child-focused and pragmatic. Romance is not a necessary condition for a happy marriage and can even be seen as unrealistic. The lack of romance is not usually a reason to seek a divorce. Marriage in modern Japan is mainly a social and economic contract between spouses and their families with children and continuation of family as the goal. That “something more” is rising in importance, however. But cohabitation and out-of-wedlock children remain the minority. In fact, a survey in 2012 showed 74.7% of women opposed the idea of an unmarried couple having a child (Dales, 2019).

Romance anime focuses on that “something more.” Tropes like making a bento box lunch and unreasonable demands (often for comedic effect) tie back into this “something more” by tapping into an idea called amae. Amae are the feelings and behaviors associated with making an inappropriate request of another person and expecting indulgence, understanding, and acceptance in return. It’s both a positive and negative word, and it can signal closeness in a relationship. Such requests and their acceptance make the partner feel needed, valued, or special. Women are more likely than men to ask for amae–as anime shows with tsundere like Asaka from Toradora exemplify–and notice their partner’s amae (Marshall, 2012).

I know all of this is pretty general; this is the context anime romance tropes exist within. The difficulty of real romance allows the fantasy of romance becomes more appealing for people. Anime romance stories often focus on how difficult relationships are: the misunderstandings, the awkwardness, the pain. The same problems we can find in the early French romances. In anime, amae plays a major role in the tropes, including the usual physical abuse of men trope. Usually the woman hits a male character who fails to comply or see her amae or overstep some boundary he wasn’t aware of. Again, this is also a violation of that “something more” idea–a consideration or understanding that goes beyond words.

One of the most important “something more” trope that sometimes ties into amae is the umbrella. You know the trope. It’s after class. High schoolers are the most common characters in romance because they haven’t entered the adult-world context of marriage and have a better chance of finding that “something more” than adults. A bleak suggestion isn’t it? Anyway, the sky is dumping rain, and one of the characters forgets his/her umbrella. Sometimes the love interest offers ichis, or the character makes an amae request. After all, walking together under an umbrella is a public declaration of a relationship status. In Japan, lovers write their names under an umbrella much like American couples write their names within a heart. The names are written on each side of the umbrella’s handle. Because Japan has a rainy season and is prone to typhoons, getting caught in the rain offers a good chance for a romantic encounter and a slow get-to-know-you walk together (Endresak, 2006). Umbrella sharing can also be a signal for a close friendship.

Anime focuses on the beginning of love instead of the continuation of it because of the context anime exists within and the target audience tends to skew young. The beginning of love is an exciting time, and it has an innocence to it as well. It offers a nostalgic time before adult concerns dominate. High school also offers an easier slip to fantasy and the fishbowl effect. The characters are forced together by the school day, making the “fated meeting” more likely to happen. Although high school romance has been overplayed. Amae sits behind many comedic events, including many misunderstandings that drive the plot forward. Some requests don’t appear to be requests without understanding Japanese culture, such as simply walking to class together or requesting to be called by a nickname. They become public declarations of some sort of relationship status. Anime likes to play these to the extreme, of course. It is fantasy.

Umbrellas are a cute motif for love. Rather logical too. You will see it with some variety, and it even poses opportunities for conflict. Many of the tropes anime uses are lifted from Western literature, as I sketched, but are given a unique spin with the influence of amae. The difficulty of real-life relationships allows stories that offer that “something more” to flourish.

References

Dales, Laura & Yamamoto, Beverley (2019) Romantic and Sexual Intimacy before and beyond Marriage. Intimate Japan: Ethnographies of Closeness and Conflict. University of Hawaii Press.

Endresak, David (2006). Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture. Eastern Michigan University Digital Commons.

Rich, Motoko (2019) Craving Freedom, Japan’s Women Opt out of Marriage. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/03/world/asia/japan-single-women-marriage.html

Umland, Rebecca A. and Umland, Samuel J. (2001) “All for Love: The Myth of Romantic Passion in Japanese Cinema,” Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 23 : No. 3 , Article 5.